A timely statistical reminder that living longer is something to be hoped for, not feared

Sir Michael Marmot has collected data which suggest that life expectancy growth rates are slowing rapidly

What’s the one thing more worrying than a rapidly ageing UK population? A not-so-rapidly-ageing UK population, it would appear.

For several years now, we’ve been drowning in ominous forecasts showing an exploding old-age dependency ratio, and projections of much higher structural spending on health care for the elderly – spending which will need to be paid for by higher taxation or lower spending on almost everything else.

Ageing featured prominently in last week’s Fiscal Risks report from the Office for Budget Responsibility.

But now, in a surreal hand brake turn, we’re invited to worry about the opposite problem. Sir Michael Marmot of University College London has collected data which suggest that life expectancy growth rates are, in fact, slowing rapidly.

Between 2000 and 2015, life expectancy at birth increased by one year every five years for women and by one year every 3.5 years for men. But since 2015, that life expectancy growth rate has fallen to one year every 10 years for women and one for every six years for men.

“I am deeply concerned with the levelling off; I expected it to keep getting better,” frets Sir Michael.

He also suggests fiscal austerity from the Government since 2010 might be a contributory factor in the slowdown. In truth, there’s not much empirical support for this link. Official data on excess winter deaths did show a spike in 2014/15, at a time when the NHS and social care were under serious strain. But they fell back in the most recent figures.

Until we have more evidence, the best argument against the underfunding of social care and the NHS is that it creates a great deal of discomfort and misery for the elderly while they are alive – something for which we have an abundance of evidence – rather than jumping to the conclusion that it is driving them to an earlier grave as well.

Sir Michael’s data should also remind us to be a little more sceptical about population projections in general.

When we are projecting over 50 year horizons, or more, relatively small changes in projected growth rates – whether that’s longevity, birth rates, or immigration rates – can have dramatic implications. And those projections will always need to be revised as new information becomes available.

There was a good example of this in the OBR’s most recent Fiscal Sustainability Report, which dropped its rather pessimistic assumption that longer lives for us all would not also be accompanied by a longer period of health – in other words, that we would simply spend a larger share of our extended lives sick or infirm.

This change lowered projected health expenditure in 2076 by 0.7 per cent of GDP – around £15bn in today’s money – relative to its previous forecast.

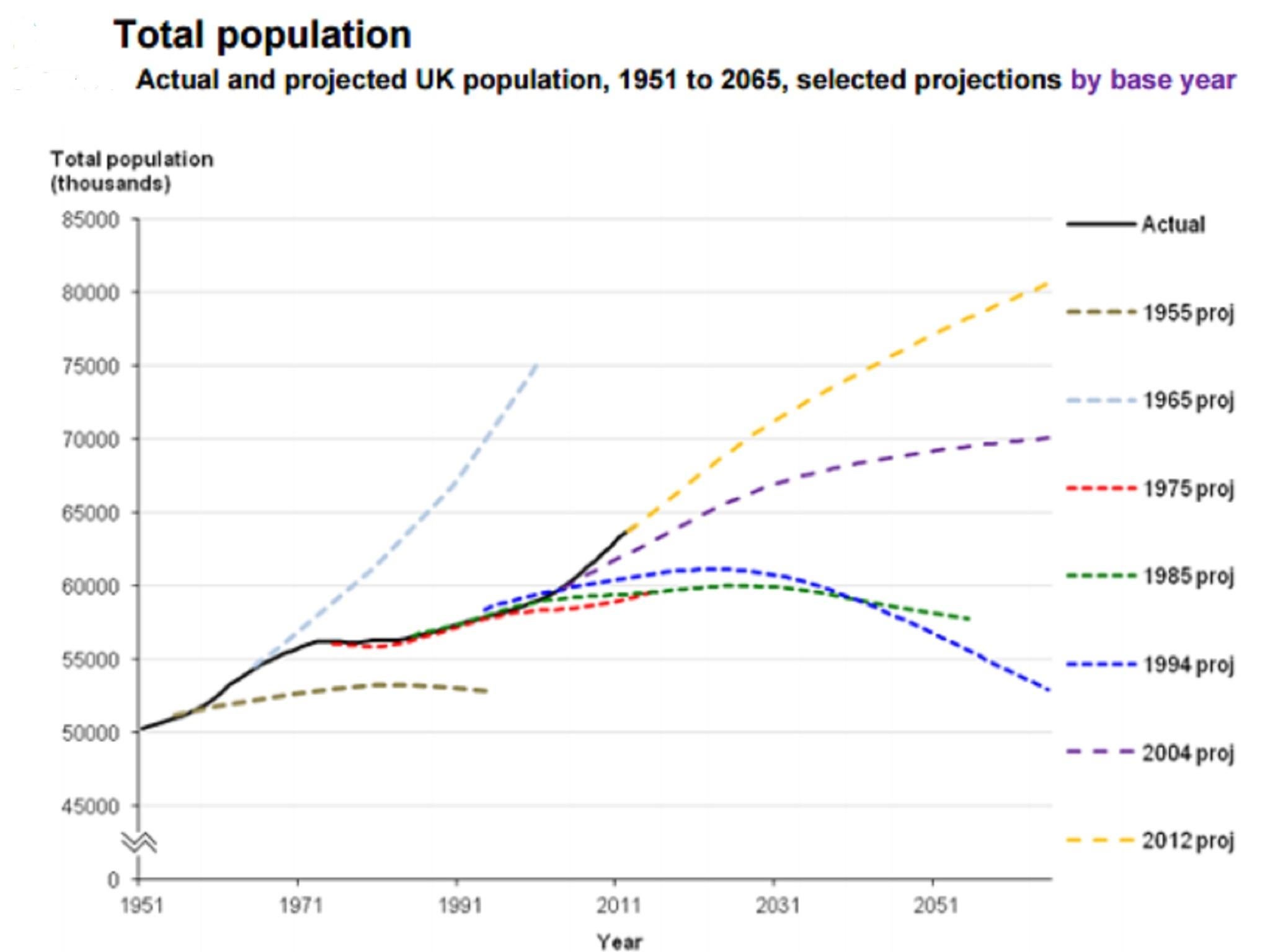

Official statisticians' future UK population projections – which underpin a great deal of analysis – have been revised dramatically over the decades, partly because statisticians did not foresee rises in life expectancy, falls in fertility, or changes in migration.

In 1955, the population was shown peaking at around 53 million in the 1980s, before gently declining. In fact, it rose to more than 56 million and then rose strongly through the 1990s.

The errors can go the other ways too. 1965 they showed the UK population hitting 75 million by the turn of the millennium. In fact, it was only 60 million at that date and still only 65 million today.

In 1971, statisticians projected the national fertility rate to bottom out at 2.4 children per woman over the next forty years. In fact, it collapsed to less than 1.7. Right through the 1980s, it was expected to pick up back to the population replacement rate of two, but it never did.

And just when this new reality had been factored in to statisticians’ projections in the 1990s and 2000s, there was a sudden pick up in the fertility rate at the turn of the millennium to 1.9.

In 1975 the average live expectancy for a man in 2010 was expected to be 71. In fact it was 78 in that year. Ever since then statisticians have been revising up their longevity projections. It's possible Sir Michael's findings will now prompt a revision in the other direction.

So are all such future projections, as Henry Ford said of history, bunk? Not at all. It is prudent to assume the baseline scenario of most forecasters that we will have a larger older population in the decades ahead, that the dependency ratio will rise, and that we will therefore need to devote a larger share of national income to caring for them.

But let’s remember that they are only best-guess projections, not unavoidable destiny.

And Sir Michael’s sobering figures are a timely reminder that – for all the challenges it brings – living longer ought to be seen as a blessing, not a curse.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies