At the Dr. Seuss Museum: Oh, The Places They Don't Go!

'The Cat in the Hat' children's author Seuss Theodor Geisel's racist political cartoons have been left out of the new Dr Seuss Museum in Massachusetts, presenting a one-sided version of him

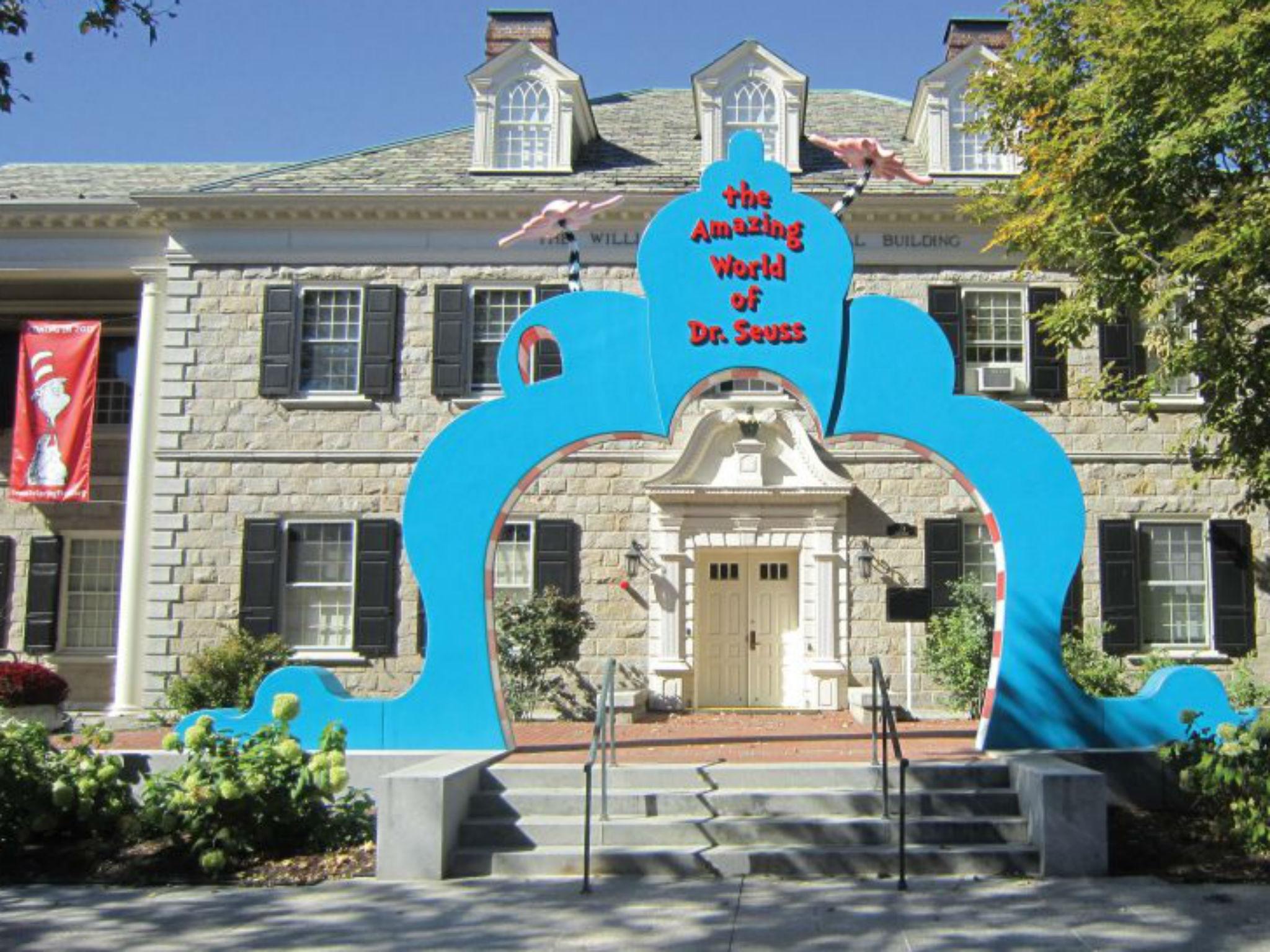

Through the front door of the Amazing World of Dr. Seuss Museum in Springfield, Massachusetts, the mind of the beloved children’s book author Theodor Seuss Geisel springs to life. The new three-floor museum is lush with murals, including one with a proo, a nerkle, a nerd and a seersucker, too. Around one corner, visitors will find an immense sculpture of Horton the Elephant from Horton Hears a Who!

But the museum, which opened this month, displays a bit of amnesia about the formative experiences that led to Geisel’s best-known body of work. It completely overlooks Geisel’s anti-Japanese cartoons from World War II, which he later regretted.

Far from the whimsy of Fox in Socks (1965), Geisel drew hundreds of political cartoons for a liberal newspaper, PM, from 1941 to 1943, a little-known but pivotal chapter of his career before he became a giant of children’s literature. Many of the cartoons were critical of some of history’s most reviled figures, such as Hitler and Mussolini.

But others are now considered blatantly racist. Shortly before the forced mass incarceration of Japanese-Americans, Geisel drew cartoons that were harshly anti-Japanese and anti-Japanese-American, using offensive stereotypes to caricature them.

While President Franklin D Roosevelt’s library has put his role in Japanese internment on full display, this museum glosses over Geisel’s early work as a prolific political cartoonist, opting instead for crowd-pleasing sculptures of the Cat in the Hat and other characters, and a replica of the Geisel family bakery.

But scholars and those who were close to Geisel note that this work was essential to understanding Dr Seuss, and the museum is now grappling with criticism that it does not paint a full picture of an author whose work permeates American culture, from the ubiquitous holiday Grinch to Supreme Court opinions (Justice Elena Kagan once cited One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish).

“I think it’s irresponsible,” says Philip Nel, a children’s literature scholar at Kansas State University and the author of Dr Seuss: American Icon. “I think to understand Seuss fully, you need to understand the complexity of his career. You need to understand that he’s involved in both anti-racism and racism, and I don’t think you get that if you omit the political work.”

One cartoon from October 1941, which resurfaced during the most recent presidential campaign, depicts a woman wearing an “America First” shirt reading Adolf the Wolf to horrified children with the caption, “...and the Wolf chewed up the children and spit out their bones … but those were Foreign Children and it didn’t really matter”. The cartoon was a warning against isolationism, which was juxtaposed with Donald Trump, a candidate at the time, using the phrase as a rallying cry.

In another cartoon, from October 1942, Emperor Hirohito, the leader of Japan during the Second World War, is depicted as having squinted eyes and a goofy smile. Geisel’s caption reads, “Wipe That Sneer Off His Face!”.

Perhaps the most controversial is from February 1942, when he drew a crowd of Japanese-Americans waiting in line to buy explosives with the caption, “Waiting for the Signal From Home …”. Six days later, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which paved the way for the roundup of more than 110,000 Japanese-Americans.

Mia Wenjen, a third-generation Japanese-American who runs a children’s literary blog called PragmaticMom, has written critically of Geisel’s cartoons and blasted the museum for leaving them out.

“Dr.Seuss owes it to Japanese-Americans and to the American people to acknowledge the role that his racist political cartoons played, so that this atrocity doesn’t happen to minority groups again,” Wenjen says in an email.

One of Geisel’s own family members, who helped curate an exhibit for the museum, says that Geisel would agree.

“I think he would find it a legitimate criticism, because I remember talking to him about it at least once and him saying that things were done a certain way back then,” says Ted Owens, a great-nephew of Geisel. “Characterisations were done, and he was a cartoonist and he tended to adopt those. And I know later in his life he was not proud of those at all.”

Geisel suggested this himself decades after the war. In a 1976 interview, he said of his PM cartoons: “When I look at them now, they’re hurriedly and embarrassingly badly drawn. And they’re full of snap judgments that every political cartoonist has to make.”

He also tried to make amends – in his own way. Horton Hears a Who!, from 1954, is widely seen as an apology of sorts from Geisel, attempting to promote equal treatment with the famous line, “A person’s a person no matter how small”.

At the museum, located amid a complex of other museums in Springfield, where Geisel grew up, the first floor is geared toward young children. Aside from the murals, there are mock-ups of Springfield landmarks that inspired Geisel’s illustrations, such as the castle-like Howard Street Armory. The top floor features artefacts like letters, sketches, the desk at which Geisel drew and the bifocals he wore.

Kay Simpson, president of Springfield Museums, who runs the complex, and her husband, John, the museum’s project director of exhibitions, defend the decision to leave out the cartoons, saying that the museum is primarily designed for children.

“We really wanted to make it a children’s experience on the first floor, and we’re showcasing the family collections on the second floor,” she says. Geisel’s questionable work would fit better in one of the adjacent history museums, where it has been displayed before, she adds.

Susan Brandt, the president of Dr. Seuss Enterprises, which oversees Geisel’s brand (a brand he resisted commercialising), argues that the museum’s critical distinction is between Dr. Seuss and Geisel.

Asked why the cartoons aren’t included, Brandt, who consulted with Simpson on the museum, says: “Those cartoons are a product of their time. They reflect a way of thinking during that time period. And that’s history. We would never edit history. But the reason why is that this is a Dr. Seuss museum. Those are Ted Geisel, the man, which we are separating for this museum only.”

The museum does, however, have references to some of Geisel’s early professional work. There is a serving tray on display that Geisel designed for the Narragansett Brewing Co. in 1941 from his days in advertising, for example, and sculptures from the 1930s.

Soon after the opening, the museum expressed a willingness to display the cartoons, perhaps sensitive to criticism that it was presenting a one-sided version of Geisel, who died in 1991. It invited Nel to a symposium this fall to discuss Geisel’s political ideology and Wenjen to the museum for a visit, something she refers to as “damage control”.

After all, contrary to Brandt’s view, the critics argue that it was the work of Geisel – the man and the political cartoonist – that inspired Dr. Seuss. “That is the work that made him an activist children’s writer,” Nel says.

© New York Times

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies