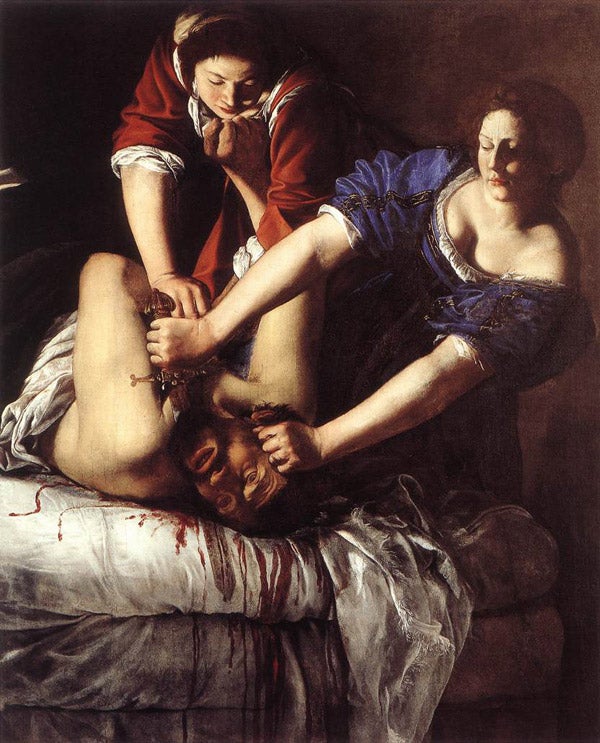

Great Works: Judith beheading Holofernes (1612-13), Artemisia Gentileschi

Museo di Capodimonte, Naples

It is a generalisation but people who get their pleasures from visiting old master galleries are generally not the sort of people who go to films in which heads are sliced off and blood goes everywhere. Perhaps it's because they have finer sensibilities. Or perhaps it's because they simply don't need to. They can get these things in old master galleries, too.

The slasher painting is an extensive genre. Western art is full of killing and cutting. Christianity is largely (though not wholly) responsible for this spectacularly violent imagery. But if there's a time when this tendency really thrives, it's the early 17th century.

The range of violent subjects is wide, from comic dentistry pictures to Christian martyrdoms to Biblical assassinations to classical suicides. And these afflictions tend to be shown close up. Their focus is not purely theatrical. The pictures are interested – in what's going on, in how it's being done and experienced.

As here: you have a sense of business, frantic but practical. Two women are trying to cut off a man's head on a bed. Artemisia Gentileschi's Judith Beheading Holofernes shows a famous Biblical assassination. The sword-woman is Judith, a Jewish lady. The other woman is her maid, Abra. Their victim is Holofernes, the Assyrian general.

Judith has got into his tent and got him deeply drunk. To judge from his naked body in the sheets and from her slipped dress, she's got him into bed too, before he passed out and they could get to work. Gentileschi pays attention to her story.

And now the drunk man has woken in the middle of their attack. Candlelight reveals the tight, desperate wrestling of limbs. Judith, she with the blade, is keeping herself at arm's length, partly, as her pursed, slightly averted face suggests, out of a revulsion from the disgusting though necessary job (how many heads has she cut off before?); partly to stay out of the fight, so far as this is possible, because both her hands are needed for leverage, grasping his head by the hair, pushing the blade through his neck.

Abra meanwhile tries to hold him down. Her calm and beautiful face is directly above him, looking straight down on to him. Her efficient hospital gestures restrain his thrashing body. They indicate her perfect managing indifference to this creature's battle for life. But both women are ruthless. Judith is disposing of a rat. Abra is drowning kittens.

There is plenty of sensation to enjoy, the blood-stained sheets, the flesh. But Gentileschi's emphasis is on how hard it is, how long it can take, to kill someone. She stresses the hows and difficulties. The strain and strength in Judith's parallel arms, driving the sword through spine and gristle, is evident. The visual confusion of plunging arms and gripping hands – whose is whose? – mimics Abra's trouble keeping control of the man, holding one arm down while another breaks free.

This violence, in other words, is violent. This outcome is clear, probably imminent, the cut is almost through, the head will come free. But that's not how the picture makes you feel. There is no sense of a clean gesture, a chop. They're in the thick of it, the carving blade still in the neck, their bodies tangled with his like lovers. The killers are intimately implicated in their murder.

This killing isn't pictured as a heroic deed, a sword raised to strike, a head raised as a trophy. It's an ongoing business, which never seems to end. Muori, dannato! Muori!, as Tosca cries in the opera: Die, damned one! And in this painting, the struggle continues.

About the artist

Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1652) is the most famous European female artist – she was a highly charged figure in her own day and is still in ours. She learnt from her father, the painter Orazio Gentileschi, and became (precociously) one of the most vigorous followers of Caravaggio, deploying high-contrast lighting and sometimes extreme violence. As a young woman she was raped by one of her father's assistant artists, which may have fired her art. She painted a series of pictures of strong and suffering women from myth and the Bible – victims, suicides, warriors – and made a speciality of the Judith story.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies