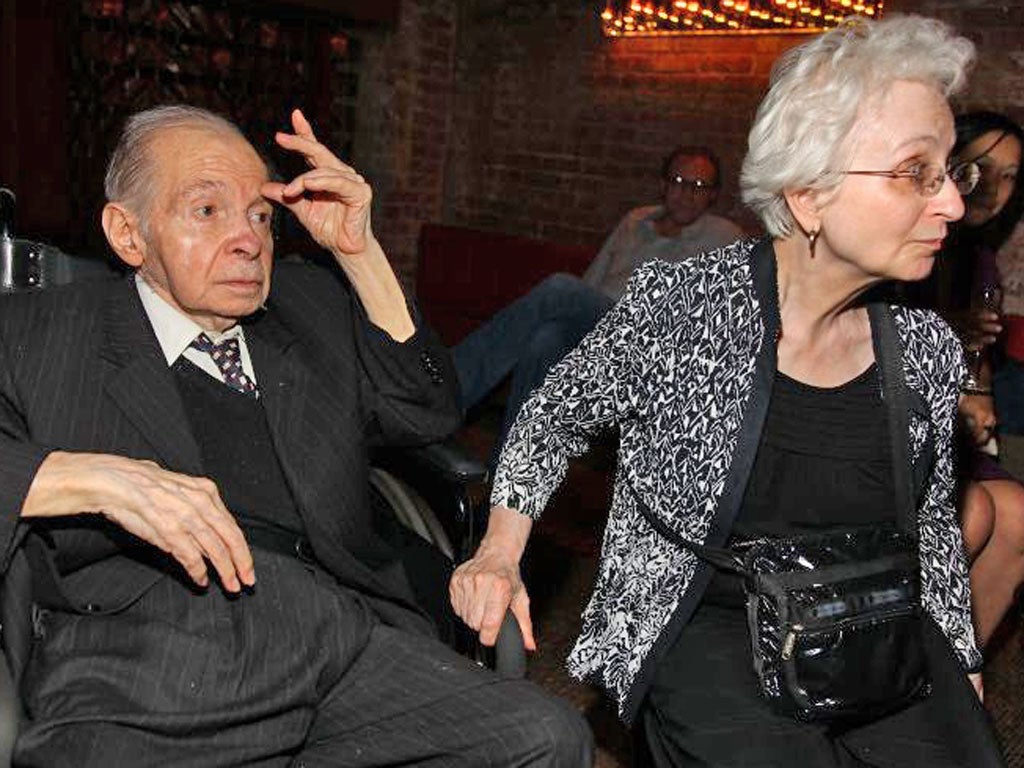

The ordinary couple with an extraordinary art collection

How Herbert and Dorothy Vogel turned a one-bedroom flat into a treasure house

On the surface, Herbert Vogel and his wife Dorothy lived an ordinary life in New York. Mr Vogel, who died on Sunday aged 89, used to work nights sorting mail at the city's post offices, and his wife was a reference librarian in Brooklyn. But over the years, the couple built up one of the world's most unlikely – and most significant – collections of modern art, and bequeathed much of it to the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

The Vogels' unlikely journey began in 1962, when they came to Washington on their honeymoon and spent several days visiting the National Gallery and other museums. Upon returning home, they began to buy a few pieces by artists they met.

Quite unlike many collectors, they weren't wealthy, living and collecting their entire lives on their salaries and their pensions. The couple did not, however, sell a single piece until the National Gallery acquired much of their collection in 1991. Estimates of its value range well into the millions. "We could have easily become millionaires," Mr Vogel told the Associated Press in 1992, adding: "But we weren't concerned about that aspect."

When they began collecting, the Vogels – known to many in the art world simply as "Herb and Dorothy" – concentrated largely on conceptual art and minimalism, work that stood apart from the better-known abstract expressionist and pop art movements, not the sort of work that was in strong demand. They visited studios and became close friends with many artists, including the husband-and-wife duo of Christo and Jeanne-Claude. In time, over almost 50 years, they amassed more than 5,000 works, including paintings, drawings and pieces that defied classification. They bargained directly with the artists, sometimes buying on instalment. Once, they received a collage from Christo in exchange for cat-sitting.

Herb, who never completed high school, and Dorothy, who survives him, had simple criteria when buying art: it had to be inexpensive, small enough to be carried on the subway or in a taxi and it had to fit inside their one-bedroom flat. "They did not collect work by marquee artists at the time, but many of them later became well known," said Earl Powell III, director of the National Gallery of Art.

What began on a whim grew into wide-ranging collection featuring many leading artists of recent times, including Chuck Close, Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, Nam June Paik, Julian Schnabel, Robert Smithson, Lynda Benglis, John Baldessari and Jeff Koons.

Artists considered it a privilege to be included in their collection and an even greater honour to be invited to their apartment for a meal. Dorothy would sometimes offer a TV dinner that she warmed up in the oven. "They were a couple without children," said Ruth Fine, a recently retired curator at the National Gallery. "The works of art became the absolute focus of their lives."

When Mr Vogel retired from the Postal Service in 1979, he used his pension to buy more art. He and Dorothy began to think about their legacy, and many top museums came calling. Eventually, after years of negotiations, they agreed to send the heart of their collection to the National Gallery. When curators began to catalogue the collection, it took five full-size moving trucks to transport the Vogels' art to Washington from their apartment.

Despite his obvious penchant, Mr Vogel could not always articulate why he liked certain works of art more than others or what he looked for when collecting. "I just like art," he said in 1992. "I don't know why I like art. I don't know why I like nature. I don't know why I like animals. I don't know why I even like myself." Washington Post

Minimalist tastes … and a minimum of fuss

Without enjoying the wealth of most serious collectors, Herbert and Dorothy Vogel amassed more than 5,000 works of art worth millions.

They began collecting in the early 1960s. Their first purchase was Crushed Car Piece by John Chamberlain, who made sculptures from wrecked car parts.

Minimalism is a predominant theme. Paintings such as Robert Mangold's X Series (Medium Scale) (1968) and sculptures such as Donald Judd's untitled galvanised iron box (1965) are cited as key works. Carl Andre's sculpture Nine Steel Rectangles (1977) follows a similar theme.

The Vogels described Robert Barry's Closed Gallery – a 1969 piece consisting of three invitations to gallery shows that informed recipients that during the exhibition, the gallery would be closed – as "without a doubt the greatest piece of conceptual art that was ever done in the world".

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments