Gillian Wearing and Claude Cahun: Behind the Mask, Another Mask, National Portrait Gallery, review: Surrealistic gender exploration

This exhibition brings together the work of the former Turner Prize winner and the late French surrealist writer and photographer, both who shared an interest in the self-portrait through photography and explored the themes of gender and identity

The subject of this exhibition could scarcely be more fashionable if it tried. It's all about gender-slipperiness, the mass appeal of androgyny, that wish we all have to slip off a mask – or put one on. Or having slipped one off with such seductive adroitness, to surprise our friends by revealing that there is yet another mask behind the first one. What fun! If only Bowie had not absented himself so shockingly abruptly.

The exhibition brings together two artists, one dead, another living. You could call it a collaboration if you like, but collaborations are never really quite what they seem. Just beneath the surface of the uneasy amity, there always tend to be fights to the slow – or quick – death of one reputation or another. And so it is here. Who wins then? Who are the contestants for supremacy?

Gillian Wearing once won the Turner Prize. She is from the West Midlands, and she is very much alive. Claude Cahun is the dead one. French, and born with the fairly dull name of Lucy Schwob in 1894, she died in 1954 on the island of Jersey. Her work is very little known – many of the prints on these walls will never have been seen in public before. Her works, generally speaking, are very small.

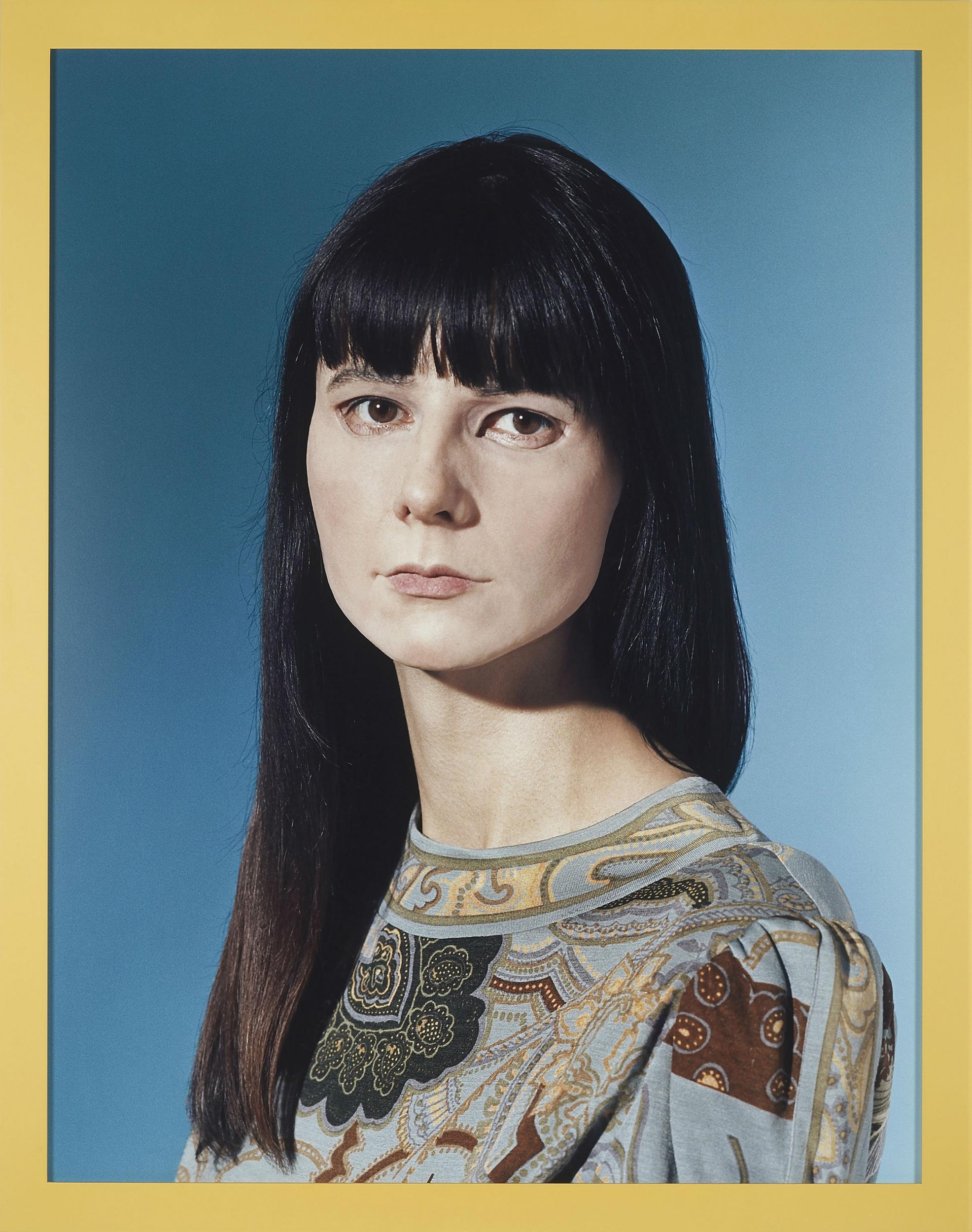

Wearing's work is large and takes up a good deal of wall space – photographs, masks, sculptures of dismembered limbs, etc. Wearing has the advantage, you could say, because she can respond and interpret Cahun's work as much or as little as she likes. She can climb up on another woman's shoulders so that we all get a better view of her. By her I mean Wearing. And she does – or, at the very least, she tries to. Cahun, being a dead surrealist, cannot answer back. (Unless, of course, something unusual happens in the coming days, and, given that she was very much influenced by André Breton, that is perfectly possible.) In fact, the skilful curation of the show has turned it into a homage of sorts by Wearing to her predecessor.

The difference between them is one of quality. In spite of the fact that we experience Cahun through nothing but small and grainy images, her vitality, her versatility, as an artist win through at every turn. By comparison, Wearing's efforts seems slow and over-calculated, programatic and slightly lumpish. Cahun's entire body is consumed by her art – the way she holds it in suspense or bends it or floats it on water – and by her obsessive wish to be ceaselessly reinventing herself as a being who is hauntingly gender neutral. It is a genuine exercise, we feel, in painful self-hazarding. There is no such pressure behind Wearing's work – in spite of its commanding physical presence on these walls and its technical slickness.

One of Wearing's works is called My Exquisite Corpse, after a famous game invented by the surrealists. The first participant person begins a drawing, and then folds the paper over so that the second, continuing it, is launching herself out, in the most fragile of skiffs, on to unknown waters. And so it goes on. Wearing's effort has been made in collaboration with her partner Michael Landy and the painter Gary Hume. It has no lift, no energy and no unpredictability. It's rubbish.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies