In-Between: A disaster zone in London strikes poetic notes after concerning itself with doom

Thomas Hirschhorns' work's initial element of surprise wears off

“Destruction is difficult,” wrote the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci in his prison cell in 1932. “Indeed, it is as difficult as creation.” Gramsci had been sentenced for his political activities in 1926 by Mussolini’s fascist police. The prosecutor at his trial famously said: “For 20 years, we must stop this brain from functioning.” They did not manage it.

Rather, the seclusion of his cell offered Gramsci the space to reflect and write down his thoughts on culture and politics, which became his 30-volume Prison Notebooks. His ideas ranged from the form of the detective novel to the importance of culture in both domination and resistance. He believed that every man was an intellectual, albeit lacking the means to express himself, and that education should serve and reflect the needs of the people.

In 2013, the Swiss artist Thomas Hirschhorn created Gramsci Monument in Forest Houses, a low-income housing project in the Bronx. The wooden clubhouse structure was built and run by local residents, who were paid $12 (£7.63) an hour, higher than the state minimum wage. In Gramsci’s spirit of public education, they offered art classes for children, a library with books on the civil rights movement, and started a local radio station. This attempt to extend art beyond the gallery space and engage with the community was a good thing. But when the summer was over, the monument came down and the jobs vanished.

Hirschhorn, now 58, is an interesting artist. It would be wrong to suggest that his heart is in the right place – he would probably reject that statement as hopelessly sentimental and ignorant of the mission of his work. He is committed to art, not to helping others. Indeed, he has said that the local residents of Forest Houses were helping him by participating in the project. He made the “decision” to become an artist relatively late – he was in his early thirties when he decided to make work that would enter art history.

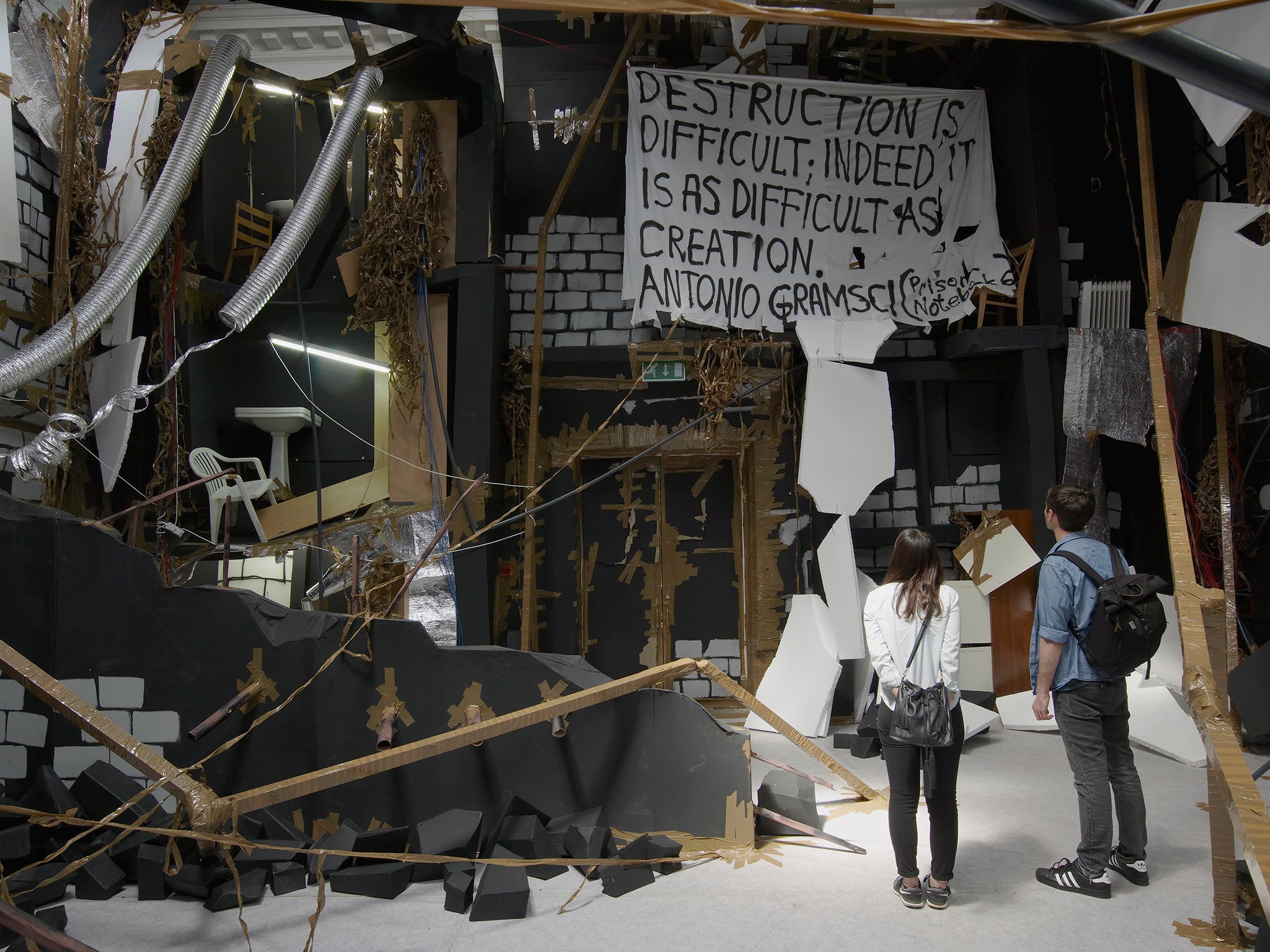

Once again inspired by Gramsci, he has created a new installation, In-Between, which has just opened at South London Gallery in Peckham. Gramsci’s quote – “Destruction is difficult” – is spray-painted in black on a white banner and hangs on the far wall of the gallery, amid a scene of total destruction. There is a vague sense of an office building following an earthquake, but the chaos is abstract. Everything seems to be falling down. Black rubble made of cardboard is strewn all over the place, bent architectural beams are covered in faux soot, masses of lengths of twisted brown duct-tape fall from the ceiling, suggesting exposed electrical wires or creeping jungle vines, come to reclaim the space and transform culture back into nature.

Is this a vision of the end of the world? A prophecy of the power of global warming? A frozen moment of capitalism collapsed? Gramsci’s quote is puzzling – surely creation is slow and difficult, and destruction is fast and easy? Natural disasters take seconds to destroy centuries of civilisation.

This is Hirschhorn’s trick. His scene of destruction in fact took two weeks to painstakingly assemble. Every bit of rubble has been overseen by the artist himself, who has said that he likes to work too much, to produce too much, to exploit himself. Over-production is a tactic of resistance. His work is about excess – his installations are typically stuffed with a superabundance of stuff that seems to revel in the trash of late capitalism, even as he critiques it.

The excess is countered by the cheapness of his materials, which he likes because they are, he says, “easily available, unintimidating, and non-artsy. They are universal, economic, inclusive, and don’t bear any plus-value”.

Brown duct-tape, which appears everywhere here, is a favourite. In the past, he has used it almost as paint, layering it densely to create a sickly, shiny surface. For his exhibition Cavemanman in 2002, he duct-taped the entire interior of Barbara Gladstone Gallery in New York, transforming it into a brown cave. Here it is used to fix the objects precariously to one another, creating a 3D collage.

Hirschhorn began his career as a graphic designer with Grapus, the Marxist Parisian group founded in 1970. The avant-garde of that era was in love with the idea of creative destruction: from Gustav Metzger’s early experiments in spraying acid to Yoko Ono’s invitation to the audience to cut pieces out of the suit she was wearing.

The scene at South London Gallery is aggressively artificial; there is no attempt to make the visitor believe in what they are looking at. Hirschhorn’s hyper-saturation of things is intended to overwhelm and dwarf the visitor, but this is offset by his DIY aesthetic, which is not menacing. His is a kind of toy terror. It feels like walking through the set of an amateur dramatics production of Armageddon.

The work has the greatest impact in the moment that you walk through the doors and see it all for the first time, but then the element of surprise wears off. For inspiration, he drew on “known pictures of destruction – destruction by violence, by war, by accident, by nature, by structural failures, by corruption, by fatality”. This has ethical implications. Perhaps he is trying to simulate the numbing effects of a hyper-saturation of media images of other people’s pain. But this feels like a cliché. A more interesting work would be one that tries to make us care.

Hirschhorn has said: “In-Between is the affirmation of a precarious dimension, the dimension of the non-guaranteed.” While the work seems to be randomly assembled, it is in fact artful, with a sculptural understanding of planes and form. The eye is drawn to detail: a pair of black doors are bandaged with duct-tape to create grids and lines that appear like an abstract painting, with bright white bricks painted on top. Another door has been boarded up with black cardboard then stabbed repeatedly with a sharp object to create the impression of bullet-holes. Has someone been executed against this door?

Top 10 art institutions

Show all 10The most affecting parts of the exhibitions are those that hint at narrative. There is a dirty toilet opposite a wardrobe, with its shelves unhinged and falling. Elsewhere, a table is tucked beneath a desk, on to which a tube of neon strip-lighting has collapsed. The person sitting at the desk would have been crushed. Detritus such as half a radiator give the impression that people once inhabited this disaster zone, living lives of work and thrift. These details add depth.

Hirschhorn’s work seems to be as much about the clichés of masculinity as those of capitalism. It often stimulates the visitor to a hysterical degree, leading him or her into the dark and frantic regions of the consumerist psyche, bloated on pornography and video games. There is a sense that breaking things, or showing things in a suspended state of being broken, is connected to vitality.

The fragment of the Prison Notebooks from which the Gramsci quote is drawn is ambiguous on the subject of creative destruction. Gramsci writes: “The destroyer-creator is the one who destroys the old in order to bring to light, to enable the flowering of the new.” Here he could be referring to the artistic avant-garde. But he goes on: “Many self-proclaimed destroyers are nothing other than ‘procurers of unsuccessful abortions’, liable to the penal code of history.” This seems a note of warning: those who destroy may simply be pathetic, not grand.

If you look up, the glass ceiling of the gallery has been covered by a black cloth, torn and stabbed. Its darkness simulates night, but light streams through the holes, suggesting stars. This strikes a poetic – even hopeful – note in an installation that is otherwise concerned with doom.

Thomas Hirschhorn: In-Between at South London Gallery, London SE5 (020 7703 6120) to 13 September

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies