Sisley in England and Wales, National Gallery, London

A sea change in our view of 'the English Impressionist'

In 1874, Alfred Sisley, French born and bred and rising 35, spent six months in Hampton Court. Apart from a spell in London in his late teens, this was the artist's first visit to the land of his fathers. There were to be two more, both brief. Otherwise, Sisley's 59 years were spent in and around Paris, where he picked up a faint accent, and French Impressionism.

Given this, you might imagine his stay on the Thames to have produced the kind of touristic views of London made by his hero, Monet. In the event, Sisley painted everything but Hampton Court Palace, his subjects – hung in a small show in the National Gallery's Sunley Room – including a new iron bridge, a regatta and a weir.

Ten years before Sisley's visit, Charles Baudelaire had published The Painter of Modern Life. The proper subject of an Impressionist, Baudelaire said, was not monuments and palaces but tea dances and bars at the Folies-Bergère. To this list might be added weirs and regattas, which Sisley, the purest of all the Impressionists, dutifully painted.

But this is to run ahead. Sisley arrived in England in May. It was only the month before that Monet had shown Impression, Sunrise, a work whose lack of finish led the sneering critic, Leroy, to dismiss the painter and his cohorts as Impressionists. Sisley couldn't have been an Impressionist in May 1874 for the good reason that the name hadn't caught on yet. And, indeed, the work seems as unsure of its artistic allegiances as Sisley was of his national ones. For all its Baudelairian modernity, there are throwbacks to an earlier time: the straw-hatted yokel in Moseley Weir, Morning looks as if he has wandered in from a Constable.

What we see in this show is thus two overlapping things: Sisley's definition of himself as an Impressionist proper, and as a Frenchman. When he returned to Britain in July 1897, it was to marry the mother of his children, Eugénie Lescouezec, prosaically, at Cardiff register office. Where once Sisley's definition of himself as a painter seemed open to national debate, now, aged 57, he was a French Impressionist. Now, à la Monet, he paints unpeopled landscapes, produced in series. There are two Cliffs at Penarth , the first hung in a modern limed frame, the second in an ornate gilded one. It takes a while to see that the pair are pendant to each other, recording the effects of light and weather on Sisley's flickering palette. Standing over the Bristol Channel, the Frenchman seems bewitched by the milky opalescence of a northern sea.

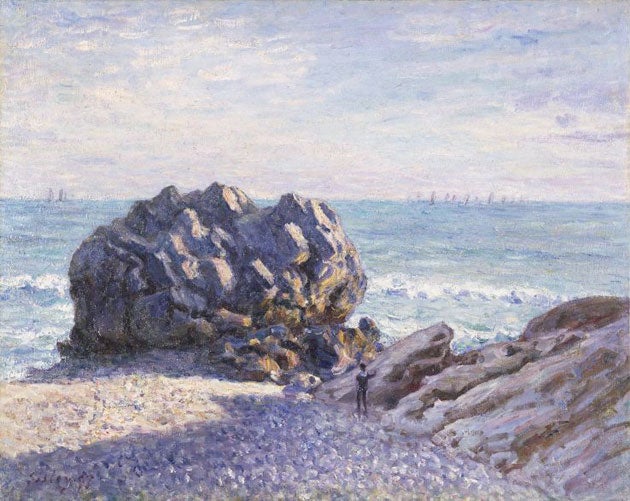

His pictures of Storr's Rock – one monolithic and alone, another backed by ships, a third whipped by waves – rejoice in the difference between the colour and light of the Welsh coast and those of the Ile-de-France. Something about the newness of what Sisley is painting translates into a palette that veers towards the abstract: acid mauves, sharp blues. The echo is not so much of Monet as of Manet.

And if it strikes us as bizarre that Sisley should once have wandered the Welsh coast, it clearly struck him that way, too. Eighteen months later, he breathed his last at Moret-sur-Loing, where Eugénie had died three months before. It is arguable that Sisley's Welsh paintings are his last, great flowering. They do, though, put paid to any idea of him as an English Impressionist.

National Gallery, London WC2 (020-7747 2885) to 15 Feb 2009

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies