Modigliani, Tate Modern, review: This exhibition is just right

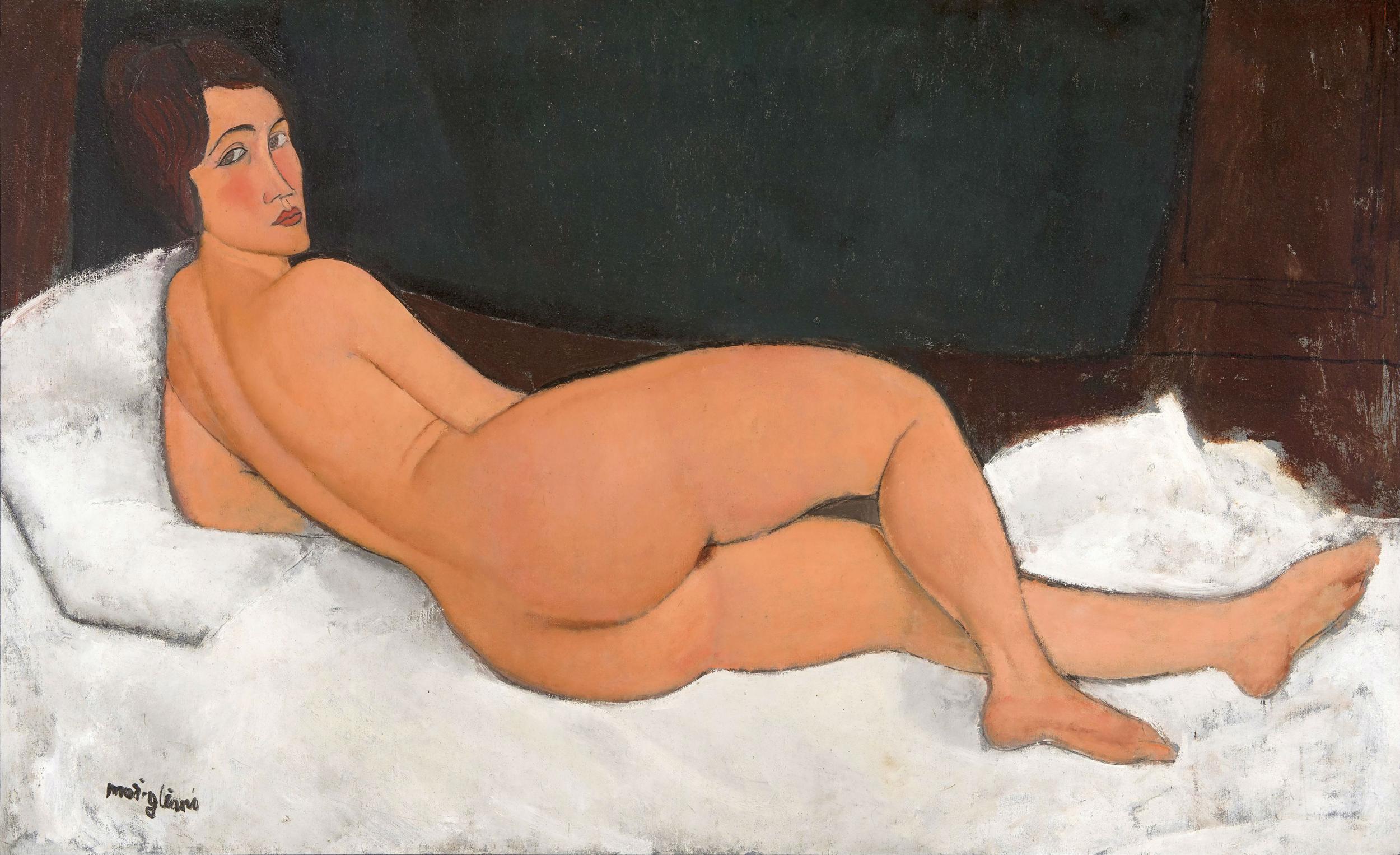

Tate Modern's retrospective of Modigliani's work features intense portraits, including one of Pablo Picasso, and 12 nudes – the largest group ever shown together in the UK

The first gallery of this show of portraits (and, oh dear, one very poor landscape) by Amedeo Modigliani, a Sephardic Jew from Livorno who arrived in Paris in 1906 with a burning ambition to be an artist, contains a single, quite small and relatively colourless picture, painted in 1915, of the artist himself costumed as Pierrot – the melancholic, tragi-comic figure who has so often been deployed to embody the reckless and often thankless pursuit of picture-making. (No one needs yet another painting). One painting! How pleasing it is to be invited to look, with so much care, at so little. It is an augury of good things to come.

So many exhibitions are far too noisy, far too cluttered, far too busy with fatuous documentation, far too heavy with information when what you crave above all things else is a quiet opportunity to look at works of arts. Not so this one. This one is just right: not too few and not too many, and all distributed throughout 10 galleries with tact, sobriety, care and delicacy.

The gallery at the creative centre of this show, the fifth, puts on display nine sculptures that he made over a two-year period – 1911-1912. Why so few? Perhaps his childhood asthma – his life was blighted by ill-health – meant that to be engaged in the dusty task of carving blocks of limestone was too hard on his weak lungs. And yet these small heads are wonderful, and they seem to prefigure, in the way that they propose themselves as a delicately poised balance of the modern and the archaic, everything else.

His range was narrow – but how inexhaustibly lovely were the best of what he managed to achieve over his short life. He died of alcoholism and other miserable complications at the age of 35. His 23-year-old partner, pregnant with their second child, took her own life days later. None of this tragedy shook his genius for his very distinctive way of portrait-making. Even in the very last works, it is as if his hand and his eye have been set apart from the decline of the rest of his body. The range is fairly small, and he sets out seeking to perfect a single thing with an unusual intensity of attack – he often painted very quickly. To describe some of the characteristics of these paintings risks descending into caricature, but let us to do it anyway: the ridiculously elongated bridge of the thin nose, with its twist; the ever rising, columnar neck; the blank swimmy blueness of the eyes; those faces, often on a delicate cant, shaped like a smoothly sucked boiled sweet. And the characteristic colour too. The hue of an uncooked steak of salmon? That’s fairly close. The outcome is so unusually distinctive that it is impossible to mistake him for anyone else, and yes, it does call to mind a strange blend of the very old – the Egyptian, for example – and the almost daringly new.

‘Modigliani’, Tate Modern, 23 November to 2 April 2018

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies