Best biographies of 2009: All manner of conflict lurks in these sketches of larger-than-life personas from Dame Vera to Floyd

The 70th anniversary of the end of the Second World War has helped along that staple of historical publishing, the "Hitler industry". Among the many books that have nourished this genre are a hefty biography of his confidant, Joseph Goebbels: A Life and Death by Toby Thacker (Palgrave Macmillan, £19.99) and an elegant and well-researched portrait of Americans in Paris: Life and Death Under Nazi Occupation by Charles Glass (HarperPress, £20), chronicling the literati and intelligentsia who stayed there against the odds.

The blockbuster of 2009, though, is Max Hastings' The Finest Years (HarperPress, £25), a muscular volume on Sir Winston Churchill's time as prime minister from 1940-1945. There's no doubt that Hastings is inspired by the great war leader, but the admiration for his military prowess is tempered by excellent research which brings to the fore the misgivings of his contemporaries. Using this as his means of attack, Hastings disentangles the less glorious actualities of the war from the mythology of Sir Winston, a man whose oratory at times seemed more deadly than the Luftwaffe.

I saw Hastings recently, signing his book. He was asking the store attendant at Waterstone's whether he or William Shawcross's new biography of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother (Macmillan, £25) was selling better. It may have just been a petty rivalry between the two popular historians, but it may also have been a gauge as to which national hero most stirred the popular sentiment. It was, according to the attendant, the Queen Mother.

Seven years after her death, her official biographer Shawcross has finished sifting through her extensive archive of letters and brought together a memorial tome that, because of her longevity, is also a history of the 20th century told through the crests and troughs of the British monarchy.

The letters, which he reprints at length, are fascinating as a record of the development of Elizabeth's rise to queenhood, but also the development of a woman. It is rare to find a life documented so well from the interior as well as the exterior, and in some ways her letters can elucidate more than mere biographical details. Her early writing, from a time nursing wounded soldiers staying at Glamis Castle during the First World War, is girlish, filled with ampersands and underlinings, and words written backwards when she is talking about boys who had caught her eye. That straightens itself into formal, if slightly melodramatic language, as Elizabeth marries into the Royal Family and counsels and sympathises with them through the abdication crisis. Her style ultimately develops in her finely written recollections of the Second World War, which in turn signal her rise to the status of mother of the nation. If anything, Shawcross's biography is there to reassure us that our love of the Queen Mother was not misplaced.

In a very different tune, the 92-year-old Dame Vera Lynn issued the second volume of her memoirs, Some Sunny Day (HarperCollins, £18.99), this year. To those who don't recall, her first rendition came out 40 years ago, but time has not dimmed British affection for the wartime sweetheart. Indeed, this was also the year that "We'll Meet Again" topped the charts (albeit in album form) for the second time. Her story – born in Essex, playing the East End music halls as a child, and hitting the new boom industry of radio in the late 1930s – is told in a chirpy but modest voice. At one point she notes that she had to buy a car to get her back from her musical engagements, making her one of a handful of women in Britain who drove in the late 1930s. There's barely a beat on how exceptional she is, but instead a few nice details on black-out etiquette for car headlights. It's a brilliant tale of hard work, patriotism and bearing the weight of a nation's love.

Dame Vera and the Queen Mother are both hallowed in 20th-century culture and, as such, there may be some veiling of truths to keep their reputations pure. For a vital account of being a woman in the 20th century, one can turn to Diana Athill. Aged 92, she has released Life Class (Granta, £25), a selection of her memoirs that chronicle the growth of a woman from a privileged childhood of horses and country estates to a middle-class existence in Andrew Deutsch's publishing house and love affairs, to a late contemplation on old age. The prose is breathtaking, and the honesty exhilarating.

Something that makes a good memoir is a sense of a life lived with gusto. Athill has it. So too does Keith Floyd, the man who became the first celebrity chef. His memoirs are sporadic, wild, fun, like talking to a drunk at the end of the night, with a fog of cigarette smoke and tragedy in the air. A tumultuous personal life, vast riches, even vaster spending, and a love-hate relationship with fame all surface through Stirred but Not Shaken (Sidgwick & Jackson, £18.99). In between sips of his preferred tipple of whisky, Floyd reveals himself as a man for whom the media was almost an amusing accident that got out of control. His true love was his cooking. As a footnote, Floyd died in September this year, just before his memoirs were published. He had been celebrating getting the all-clear from cancer that day with a hearty lunch of oysters and partridge, a bon viveur to the last meal.

Two other bon viveurs were subjects of biographies this year. One was of the Tory MP Alan Clark, by Ion Trewin (Weidenfeld, £25), who had previously edited Clark's riotously indiscreet diaries. One wonders what a biography could add to Clark's own writings, which were filled with more self-criticism than even a hostile critic could manage. What Trewin does is pull together a comprehensive picture of Clark, the renegade politician, the philandering yet hopelessly faithful husband and the vain but vulnerable man, and finds the legacy beyond the diaries. It may not have the style of Clark's writing, but it does put some substance into the Clark swagger.

The other bon viveur is Charles II, about whom Jenny Uglow has written a classically brilliant biography, A Gambling Man (Faber, £25). Examining the first 10 years of his rule, which marked the Restoration of the monarchy, Uglow portrays a double-edged king, one who was given the soubriquet "the merry monarch" for the return of pomp and finery to the Royal Court, the other a man who had used pragmatism and dark politics to secure the nation, and his own throne at the head of it.

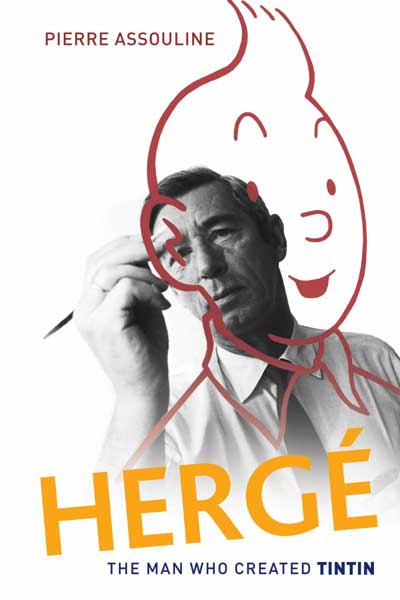

Finally, it is rare that a biography of a Belgian makes it across the Channel, so an honourable mention must go to Pierre Assouline's volume Hergé: The Man Who Created Tintin (OUP USA, £16.99). Born George Remi in Brussels, a young man who doodled his way through school eventually reversed his initials to come up with his pen name and landed a slot doing cartoons on a news- paper. And thus Hergé and Tintin were born. Assouline researches in meticulous detail and draws together the lives of the fictional character and his creator. An intriguing biography and, if nothing else, one learns a lot about Belgium.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies