Boyd Tonkin: Schoenberg was looked on as something shocking - now, anything goes

The Week in Books

During the opening weekend of the Southbank Centre's year-long festival built around Alex Ross's landmark book The Rest is Noise, Gillian Moore - the centre's head of classical music - re-told a story about Arnold Schoenberg. In 1914, the Viennese composer - a patriot for all his radical tendencies - enlisted in the Austrian army. An officer supposedly said to him (and I paraphrase very liberally), "Schoenberg? Aren't you the 'orrible little man who composed all that ghastly tuneless music?" To which the hapless avant-gardist replied, "Yes, sir, Sorry, sir. But somebody had to do it, sir."

Did somebody have to do it and, if so, why? As the centenary of the First World War nears, it's no surprise that contemporary culture has begun to return to its origins in the convulsive years before, during and after the deluge of 1914-1918. Schoenberg loomed large in the first tranche of events inspired by Ross's magisterial panorama of 20th-century music and society. Listen to his achingly gorgeous Verklärte Nacht of 1899 and the late-Romantic sound-scape just about survives. By the time of the eerie burlesque of his Pierrot Lunaire in 1912 - deftly performed by musicians from the Royal Northern College of Music - a bomb has gone off in the palace of art. From Freudian psychoanalysis to Einstein's 1905 paper on special relativity (charmingly explained by the mathematician Marcus du Sautoy with the aid of his twin daughters), these explosions in the mind preceded the carnage of the trenches and the fall of old empires. Whatever the chains of cause or correlation, the West then entered an era of upheaval that still persists.

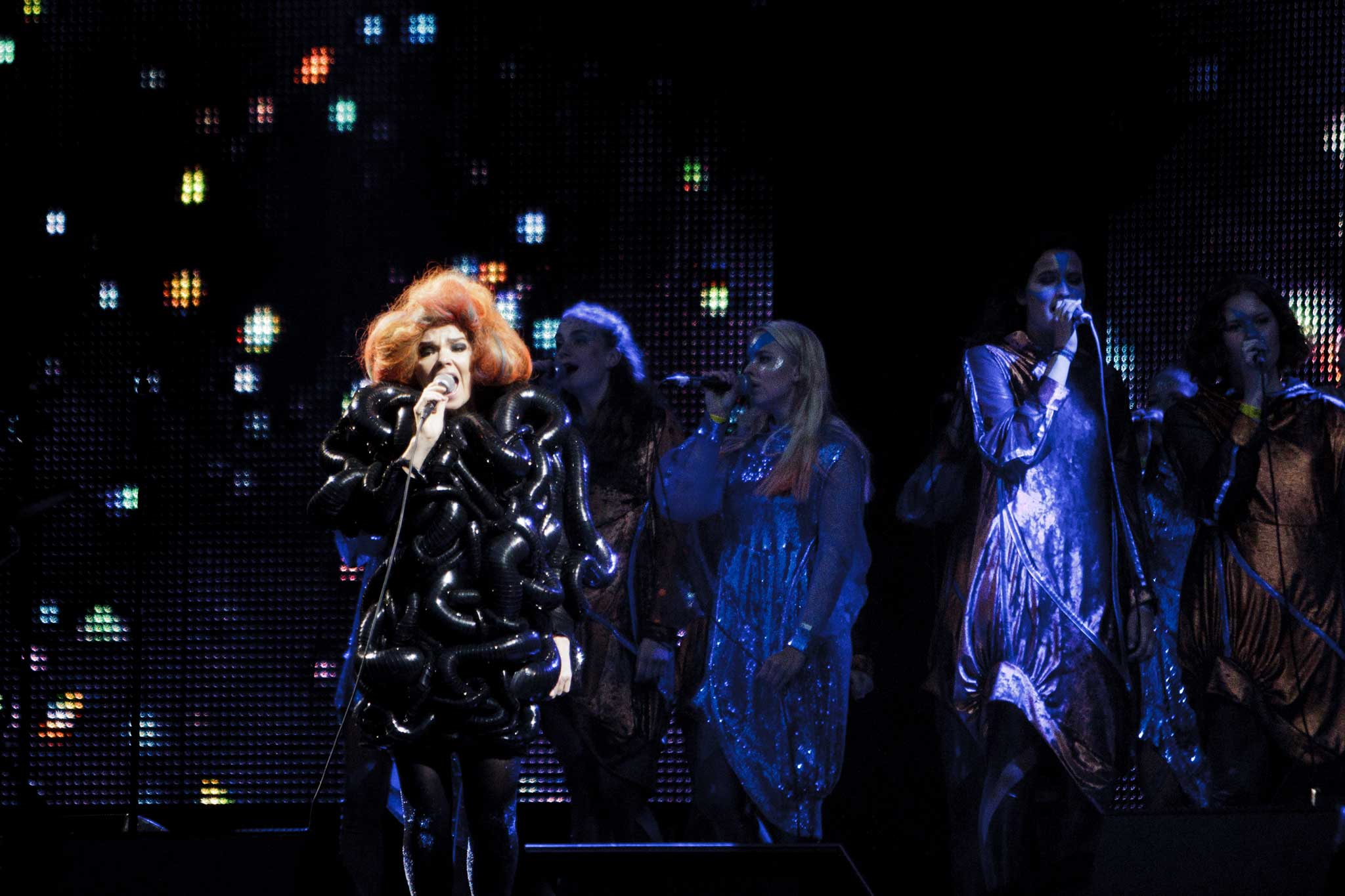

That Modernism - to use the handiest single-word formula - still retains its power to baffle or shock hints that we still live within its parameters. Björk, a musician Alex Ross much admires, loves Pierrot Lunaire and has performed its sinister-ethereal cabaret role. But if even a pop star famous for her bold experiments were to plant Schoenberg into a mainstream gig, plenty of fans of the elfin Icelander would still turn as pale as Pierrot's chalky face.

The anniversary of 1913, the year of riotous fisticuffs in the audience at the premiere of Stravinsky's Rite of Spring in Paris and at the revival of Schoenberg's Chamber Symphony in Vienna, is a perfect occasion to celebrate the divisive excitement of golden-age Modernism. All the same, it's one thing to hail, and learn from, the unfinished Modernist revolution in the arts; quite another to make a fetish of its almost-antique monuments and masterpieces.

In the case of literature, I tend to think of the diehard Modernist clique as the "1922 Committee", after the Tory backwoods posse of that name. That was the year in which the dying Proust last worked on In Search of Lost Time and Joyce published Ulysses. For the literary 1922 Committee, nothing much of any value has happened since - except in so far as writers still follow those masters. Such a loyalty can yield invigorating outcomes. Will Self's novel Umbrella, arguably his best, sought to resuscitate this "classical" Modernism of the 1920s.

But Self, or any other artist today, can and does choose this style off the shelf. It's yet another option in an age of limitless eclecticism. In other words, by signing up to Modernism in 2013 you prove yourself as just another Postmodernist in the era of "anything goes". That is our plight, and privilege: a long march away from the "somebody had to do it, sir" sense of destiny that drove Schoenberg. Last weekend, Alex Ross compared music now to the 1920s, another pick-and-mix decade without a single "dominant trend". Should we consider that plurality as liberty, or loss? So long as 2014 spares us from the miseries of 1914, I'll enjoy the cacophony.

southbankcentre.co.uk/therestisnoise

Winner: the unlikely feminist avenger

Few of the tributes to the late Michael Winner have made much of his strange interlude as a radical-feminist film-maker. In 1993 he directed (with stars Rufus Sewell and Lia Williams) a movie of Helen Zahavi's sulphurous - and elegantly written - novel Dirty Weekend, in which a Brighton woman goaded to breaking-point by sexual harassment goes on a vengeful killing-spree. It seems Zahavi gave up fiction, although Dirty Weekend was republished last year. But don't expect to catch the gory Winner flick on TV soon.

How mighty Maus showed the way

Over the years that we have run our "Book of a Lifetime" column, hardly any work has ever been chosen twice in quick succession. A few weeks, ago, the graphic novelist Bryan Talbot (the winner, with Mary M Talbot, of the biography category in this year's Costa Awards) picked Art Spiegelman's ground-breaking memoir Maus. This week (see page 35), the up-and-coming French novelist Laurent Binet pays his own homage to the same work. It could be that, in the UK, the pictorial narrative has just about reached the tipping-point towards general esteem and literary credibility that it has long enjoyed in France – with a recognition that the form can showcase many other qualities beyond its visual-verbal mix. Next Tuesday, the overall Costa winner will be decided. A victory for the Talbots' Dotter of Her Father's Eyes would surely clinch the case.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies