Epic rides on the cycles of history: Will the West crash while the East booms?

Ian Morris is the latest historian to take the global view. Boyd Tonkin looks at modern tales of rise and fall

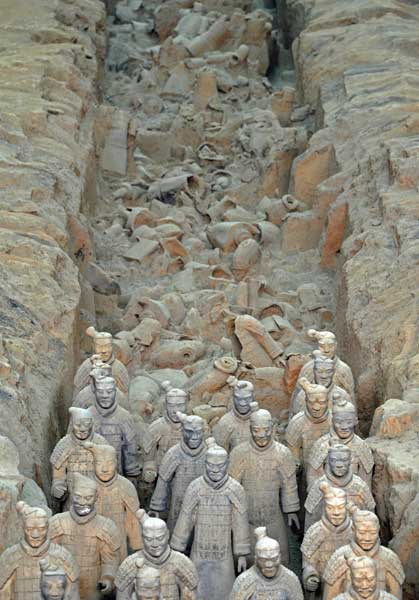

Blame it on the spending cuts. One year, the navy's shipbuilding budget was axed. Soon after, the government refused to send craftsmen to the yards. And so course of the planet's history changed. Perhaps. This happened, after all, in the world's richest and most powerful country – China - in the late 1420s and early 1430s. Not only did the Ming empire at that point benefit from printing, guns, magnetic compasses and countless other technological boosts to advancement that Europe had scarcely yet come across. China had even enjoyed a thousand-year head-start with - the wheelbarrow. No contest, then.

We all want history to demonstrate a pattern, even a purpose. Whether you choose to view the past as progress ("onwards and upwards"), recurrence ("here we go again") or a series of catastrophes ("we're all doomed"), a strong narrative arc always appeals more than a chapter of accidents: "one damn thing after another". The direction can be downward, so long as the path leads firmly on. In the 1770s and 1780s, Edward Gibbon pioneered the bestselling panoramic history not with an epic of uplift but with his Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. That story went somewhere.

Back to China, c1430. After the death of the modernising Emperor Yongle, Confucian mandarins in the civil service staged a conservative comeback. They starved the 300-ship "treasure fleets" of Admiral Zheng He of the resources they needed to push beyond the eastern oceans. Compared to the 27,000-strong, scientist-packed, state-of-the-art expeditions that Zheng He (a eunuch of Muslim origin) led after 1405, the three tiny ships that Columbus of Genoa sailed west in 1492 were pitiable tubs. Their fantasist captain took with him a half-hearted commission from a sceptical pair of minor monarchs who had only just won nominal control over a multi-ethnic mish-mash they called "Spain". It would have looked to Ming-dynasty China as a sparrow to an eagle.

Yet the sparrow contrived to overfly the eagle – for a while, at least. Somehow, a few Atlantic-seaboard cultural nonentities unleashed European long-range power. An ecological and economic revolution, with transatlantic crops and cash feeding and arming strong new states, recruited the new world to refresh the old. And this global supremacy – however brief, however unlikely – has for centuries encouraged big-picture historians to romp around in an adventure playground of rival theories.

In the 19th century, the master narrators of Europe and north America tended, in an orgy of backslapping, to congratulate their readers and themselves. The rhetoric of Herbert Spencer, Victorian apostle of progres, prompted Darwin to import the term "evolution" into his work. To be "Western", or European, or just British, was to belong to a tribe (or even race) of clever, plucky underdogs whose skill and nous (or even genetic endowment) had rightly secured for them Kipling's "dominion over palm and pine".

All that changed as Western power faltered, tottered – and then, in successive bloodbaths after 1914, consumed itself. In that same poem, "Recessional" (written for Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee in 1897), Kipling had warned that "all our pomp of yesterday/ Is one with Nineveh and Tyre!". Western visions of decline ran ahead of the evidence. And when the evidence came in, the historical epics of innovation and conquest – whether they chose science, politics, money and credit or race as the motor of European dynamism – took on a much darker and more foreboding cast.

Oswald Spengler published his (literally) epoch-making Decline of the West in 1918, just as four European-led empires – the Ottomans of Istanbul included - crashed. Between 1936 and 1954, Arnold Toynbee's A Study of History dwelled more on the winters than springs of major civilisations. Among the surviving optimists, Marxist inevitability might have supplanted liberal patterns of progress. Yet even the Australian Marxist archaeologist V Gordon Childe, in his influential What Happened in History (1942), took such a broad view of culture that it surely left most readers with respect for the distinct values of a range of peoples rather than a yearning for the new proletarian dawn.

As Ian Morris repeatedly argues in Why The Rest Rules – For Now (Profile, £25) – his own provocative and extraordinary contribution to wide-screen comparative history – "each age gets the thought it needs". In the embattled West, the age has for long required ideas, if not of decline alone, then of challenge, rivalry and takeover. Collapsing empires, genocidal wars and nuclear-armed stalemates all fed this need. Now another sturdy plot-line – the rise, or rather the return, of some version of Asian hegemony – has galloped into fashion. Treatises on the Chinese, the Pacific or (less often, but now moving ahead fast) the Indian future proliferate.

Should serious historians today indulge in this kind of broad-brush, cross-cultural narrative, especially when it turns on tales of "rise and fall"? Expert opinions differ sharply. Historian of the British empire Professor Bernard Porter, of Newcastle University, comments that "My own historical instincts are very much against seeing the complex interactions between peoples, nations and cultures in simplistic 'rise and decline' terms". For him, the equation of history with the play of power "tends to place a misleading degree of emphasis on aspects of those relationships that it is thought can be measured in terms of power - military, political or economic."

In contrast, for Paul Cartledge, professor of Greek history at Cambridge University, such big stories are "precisely the business of historians, especially ones who like myself call themselves cultural historians. In particular, cultures/civilisations that produce 'empires' - whether empires of the fist and boot or empires of the mind - tend to be especially worthy of such historical study" – because of their widespread impact. Cartledge argues that "'Rise' and 'decline' are partly subjective evaluations... but only partly". Besides, for an ancient historian, "the topic is a no-brainer, since the founding father of (critical, objective, explanatory) history tout court, Herodotus, was also the founder of the West-East cultural dialectic."

To Stephen Howe, professor of post-colonial history at Bristol University, the trouble often stems from the definitions themselves: "Thinking of global history in terms of distinct, successive or rival 'civilisations' has itself a long, but in the main not very distinguished, history". For Howe, "the most recently popular version of the 'clash of civilisations' idea, that associated with Samuel Huntington, is both notably crude in itself and has been used for some very bad political ends. Thinking critically about the history of such ideas... is an important task. Historical thinking in terms of those ideas is a very different and usually far less creditable one."

Undaunted, and with his patent blueprints for "East" and "West" to hand, Ian Morris offers a specific spin on the tilting axis of the globe. He is no modern historian but a wide-striding classical archaeologist who thinks in millennia rather than centuries. Born in Stoke-on-Trent (he includes a childhood picture of himself, with toy Dalek, amid the Christmas Day consumer cornucopia of 1964), he has taught since 1995 at Stanford University in Calfornia. That patch of the West certainly still rules for now.

His book does not try to tell a complete global story of "the rise and fall of great powers". Critics will question its relative neglect of South Asia, or the major Central and South American cultures. Instead, from the end of the last Ice Age to the banking meltdown of 2007-2009, Morris referees a 16,000-year stand-off between two great blocs of humanity, centred in the ever-shifting "cores" of East and West.

For all its bones of contention, this book is a true banquet of ideas. Agree at every point or not, Morris has pulled off a stupendous feat of intellectual generalship. His "laws of history" set a constant human biology and (to a lesser extent) society against the pressures of geography: for him, the decisive factor. "Maps, not chaps" determine his story. From the central Asian steppes – for long a gateway, then a barrier – to the relatively narrow and navigable Atlantic that brought America to Europe, the lie of the land, and the swell of the sea, always exert a shaping force.

Far from being aliens, in his view East and West had and have almost everything in common. Having briskly polished off racial theories of social change (which have "no basis in fact"), he traces the ebb and flow of power between these intimate antagonists. If that is what they are: one of Morris's graphs (and he adores graphs) pictures such an exact correlation between development East and West that "it is hard to tell them part through most of history". Clash of civilisations? More like a neck-and-neck parallel ride.

Incidentally, Morris puts south-western Asia and the eastern Mediterranean firmly in the Western camp. So Persia, Egypt, Iraq, Turkey and so on in turn nurture the far Atlantic shores. By 700, "the Islamic world more or less was the Western core". For the most part, his idea of "East" means China's heartlands and hinterlands.

Morris devises an elaborate statistical machinery to the calculate relative social development. Using criteria such as "energy capture", "urbanism" and "information processing", he sifts and tabulates the historical record to yield figures that will allow for comparisons across both space and time. Sceptics (many, no doubt) will scold his number-crunching brio as sheer hubris. This is, as he admits, "chainsaw art". Still, the chainsaw slices the evidential logs into shapes that stimulate and often illuminate.

Within societies, he detects the same processes at work both East and West. Human beings – "lazy, greedy and fearful" everywhere – will always seek for the fast buck, the short cut, the cushy number. Those vices – or virtues - drive their development, from sedentary agriculture to ocean-going exploration. A certain kind of popular sociobiology seems to be at work here. At least, whereas previous wide-screen histories favoured some creeds, cultures or classes above others, Morris goes in for the equal-opportunity insult. Humanity itself has a selfish eye for the main chance.

These smart, lazy fixers (us) will thrive best where physical conditions bless them most. Yet via the "paradox of development", prosperity in these "cores" can soon lead to overheating, overstretch and breakdown. Then the "peripheries" will take up the baton of progress, exploiting the "advantages of backwardness" to outpace the old centres of civilisation. In recent years China, the original core that faded into a periphery, has rocketed back to the centre of the stage.

What of the East-West balance of power? Morris rejects both "lock-in" theories of predestined superiority, and "lucking-out" views of happy (or unhappy) accidents as the fuel for success or failure. According to his statistical model, East and West have tracked each other closely. But in ancient times the West had a slight edge – geographical, not cultural – and kept it through the age of agricultural empires.

Then, after Rome's downfall, the East took off and took over. So here's the headline story from his whole epic trek: between around 550 and 1770, East Asia enjoyed a more or less unbroken run of social, scientific and economic supremacy. Not even the Renaissance (as he shows, China had its glorious upsurge of learning and science earlier) could make much difference. Then came the Industrial Revolution – first in geographically favoured, low-authority Britain, then elsewhere in the West. With steam power, "fossil fuel made the impossible possible". Its interaction with the thriving "Atlantic economy" sealed the deal. Thus "The West rules because of geography".

One non-racial version of Victorian progress might even agree with that. What next? Morris argues against a reversion to the Asian-dominated norms of the 1200 years after the fall of Rome. Rather, globalisation of commerce and technology has changed all parameters. Thanks to calamitous pressure on natural resources and to chaotic climate change ("global weirding" he calls it, after Thomas Friedman), we're all in this together now.

Either we break through into a utopian realm of biotechnology, robotics and "the merging of mortals and machines", or else the "Nightfall" of planetary catastrophe descends. Either way, "East and West will be revealed as merely a phase we went through". A savvy reader in Beijing might conclude that, just at the moment when the prospect of an extra-time Eastern match-winner looms, the ref has moved the goalposts. But then Britannia – whether in Stoke-on-Trent or Stanford – often did prefer to waive the rules.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies