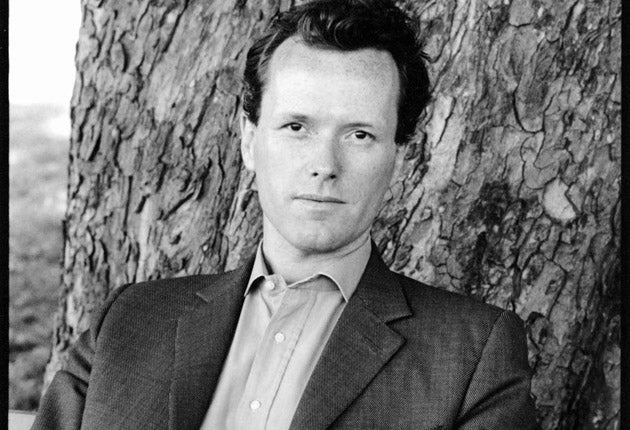

At Last, By Edward St Aubyn

The fifth and final part of Patrick's story is set on the day of his mother's cremation and, as ever, is a beguiling blend of wit, intellect and compassion

Each of Edward St Aubyn's Melrose novels, of which At Last is the fifth, enthrals, but in sequence, their power is synergistic.

They relate the tale of a horrifically dysfunctional family: doctor David, his wealthy wife Eleanor, and their child Patrick, who is raped by David and develops addiction problems. Patrick's craving for maternal love leads him to marry caring Mary, but after two sons arrive, Mary's attention shifts. Patrick's need for unshared affection then leads to his affair with Julia, and he is angst-ridden at Eleanor's decision to leave the family pile to a shaman – or conman – Seamus.

St Aubyn's characteristic blend of acid wit, intellect and compassion is plaited through At Last, which is focused on a single day – that of Eleanor's cremation, in 2005. Figures from Eleanor's past, such as her ghastly sister Nancy (as voraciously acquisitive as Eleanor was pointedly unmaterialistic) have assembled.

St Aubyn's acerbic humour is wonderful but this is also a psychologically astute book. When the parallels between Patrick and St Aubyn are considered (St Aubyn has revealed that he shares Patrick's history of abuse and addiction), the novel seems strikingly raw and honest, too. Patrick is still searching fruitlessly for a reason for his mother's failure to protect him, and even when he confronted Eleanor with his rape, Eleanor had competed for victim status. But there are signs that Patrick is progressing – the anger at disinheritance that dominated Mother's Milk is here refracted into a realisation that he needs to let go of the past in order to escape it.

One reason why you get more from reading the whole Melrose saga than diving into one of the novels cold is that the complex feelings that Patrick has are layered like rock strata, each dependent on the last. Some St Aubyn newcomers reading Mother's Milk were dubious about Patrick's sense of entitlement: why should he inherit a mansion in France? But in disinheritance, material possessions are emblematic of withheld love; the individual has sought affirmation, approval and affection throughout life, and being cut off is the final raspberry on a sundae of rejection. Patrick also makes it very clear that the Saint-Nazaire home was a sanctuary to him.

In At Last, Patrick has recently left the Priory, so the language of psychotherapy is prominent, but there is no self-indulgence. When Patrick refers to projection ("you spot what you've got and you've got what you spot") or repression ("a different kind of burial, preserving trauma in the unconscious"), it is in terms which are smart and easy to understand. And St Aubyn is still deliciously wicked in his satire. Nancy is a parody of venal greed: "She had no cash for taxis, and her swollen feet were already bulging out of the ruthlessly elegant inside edges of her $2,000 shoes. People said she was incorrigibly extravagant but the shoes would have cost $2,000 each, if she hadn't bought them parsimoniously in a sale."

There are two small flies in the ointment. The children's voices are not always convincing. In Mother's Milk, Robert's "memory" of being born was sufficiently bizarre to excuse it from earthly criteria, but here it jars when six-year-old Thomas is familiar with the word "ember" or asks about souls. (There may be a poignant reason for St Aubyn not always being able to do kids convincingly – abused children grow serious too soon, then spend the rest of their lives looking for a parent, as Patrick does.)

If other characters' voices are occasionally too polished to be convincing, this criticism relates more to St Aubyn's intellect and sharpness: most of his characters are capable of arch comments and wry irony. Julia is able to banter and quip; the monstrously egotistical Nancy can be hilarious; and even Mary, whom one might expect to be preoccupied and earth-mothery, is not beyond the odd sardonic comment.

But these are very small problems in a shimmering work of multiple strengths. Even minor characters surge with fascinating foibles: Mary's mother indulges in "complacent self deprecation", relating long anecdotes about herself, with feigned self-ridicule not quite masking her narcissism. And St Aubyn's ability to pierce the façade of moneyed politesse that veils cruel, hypocritical behaviour is as acute as Alan Hollinghurst's in The Line of Beauty. A flashback to a 1970s scene in which a black servant was refused leave to attend his brother's funeral raised a tear in this reader.

The final coming to terms is not an epiphany, as that would suggest a clarity of vision through which peace is reached, and with childhood trauma, the circular questions never end. But At Last is as close to a resolution as Patrick will ever come and ends, if not with unrealistic optimism, then at least with hope. Demons are forever, but we're privileged that St Aubyn chose to share his with us.

To order any of these books at a reduced price, including free UK p&p, call Independent Books Direct on 08700 798 897 or visit independentbooksdirect.co.uk

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies