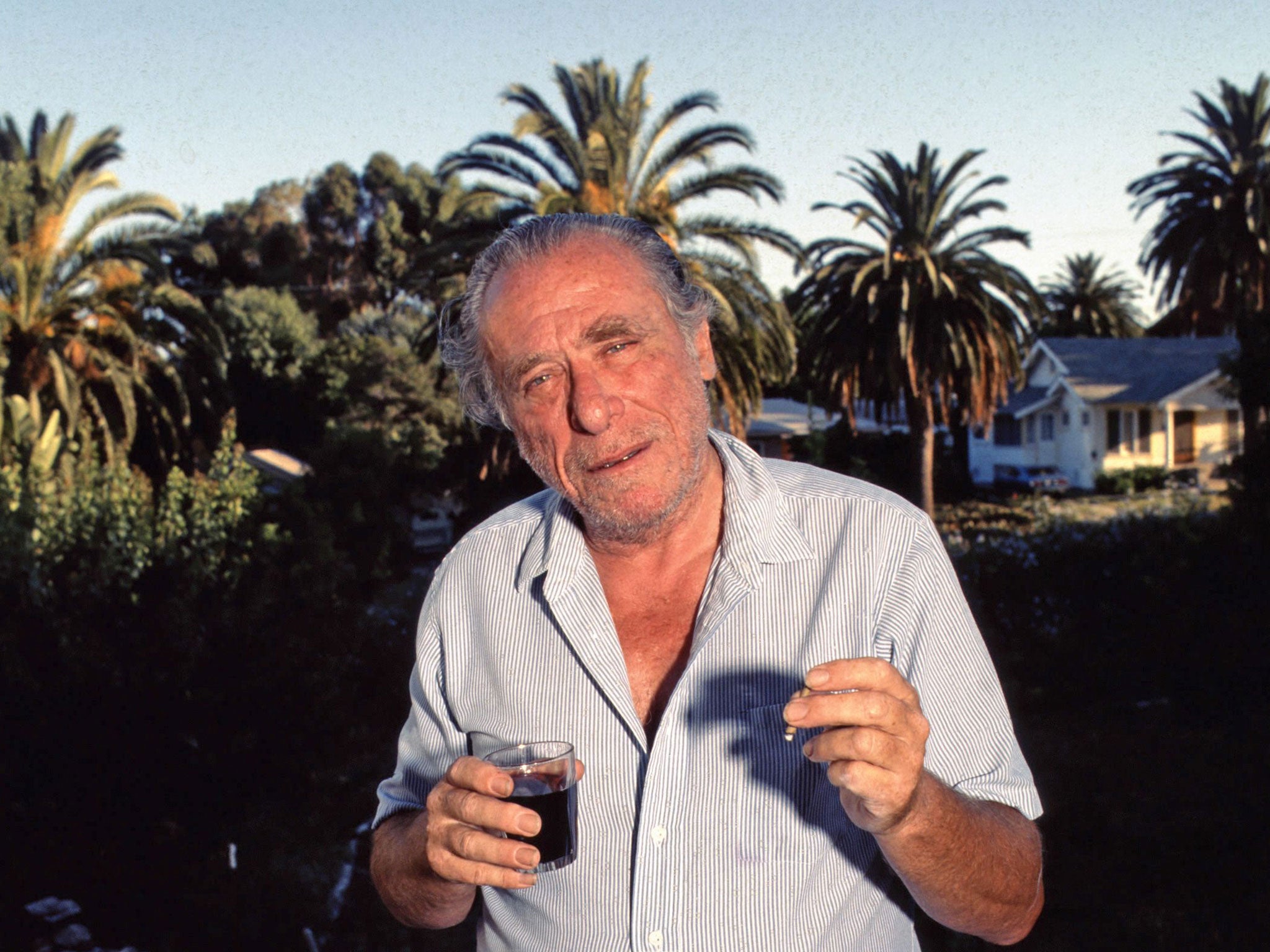

Charles Bukowski was 51 when his first novel was published – but he more than made up for lost time, producing numerous novels, screenplays, stories and poetry collections before his death, aged 73, in 1994. Death has hardly slowed his productivity and Bukowski's latest book of never before published writings in which he discusses the "pleasant disease" of his vocation in provocative, booze-soaked letters, is by no means the first collection of his correspondence to appear. When it comes to barrel-scraping, Bukowski is up there with Philip Larkin.

Where Larkin favoured structure, Bukowski thrived on spontaneity and aimed to capture in words what he called "gut-life". He disdained literary circles and academic discourse: "Those who have been writing literature have not been writing life," he says in one letter and elsewhere he claims: "(I) get more knowledge of life by talking to a garbage man than I could by talking to TS (Eliot)". He complains that "intelligent people jaggle my nuts" and signs off to the publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti: "I palm my battered nuts and shiver in the sun."

Reading about Bukowski's nuts is unpleasant, and even a short book like this one can make for a claustrophobic experience. Fans of his poetry and novels, which include Post Office (1971) and Ham on Rye (1982), will know that Bukowski is unapologetically crude. His letters, in which his prose is often as vital as it ever was, alternately read as a committed artist's lively meditations and the self-obsessed ramblings of a dirty old man.

The early letters contain obvious proclamations ("Good art shakes you alive") and lack self-awareness: "I'm not for arguing, bitching." But Bukowski is for bitching – John Keats ("a bag of shit"), William Faulkner ("phoney as greased wax") and Henry Miller ("Star Trek contemplation sperm-jizz babble") are all slammed. Women writers are non-existent to Bukowski who dismisses his critics as feminist enemies of free expression, or contrasts their easy lives with his experiences on skid row. Later letters, to his publisher, and to his idol John Fante, are more thoughtful.

Some of Bukowski's correspondents were heroically long-suffering, so more information on them would have been useful. Bukowski's letters do not paint a portrait of an epoch, as Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell's correspondence does, in part because he eschewed artistic movements. According to Bukowski, members of Charles Olson's "Black Mountain School" of poets lack the courage to "fail alone", but perhaps Bukowski protected his solitude because his day job (at the post office) already exposed him to people in ways most writers wouldn't understand.

In his letters, and the drawings which illustrate this volume, Bukowski records the intensity of his isolation and the scale of his ambition. He can be self-mythologising and stupid (writing novels, stories and poems is "like having three women") but his perseverance is admirable. His fieriness is refreshing today when writers are expected to be amiable and available.

Sometimes, the reader may wish he would grow up but, two decades after his death, Bukowski's voice still resonates: "There is nothing more magic and beautiful than lines forming across paper. It's all there is. It's all there ever was. No reward is greater than the doing."

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies