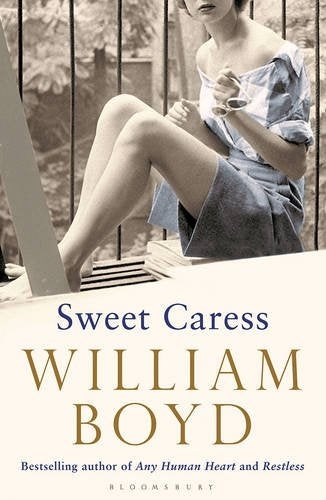

Sweet Caress, by William Boyd - book review: Blurry snapshots of a life captured by a bloke in drag

Bloomsbury - £18.99

William Boyd’s new heroine, Amory Clay, does love a penis. Her first lover has “a pinched bud of his thick foreskin (which) made his penis look tuberous, vegetal”. Her second has one that is “smaller … though thicker and more heavy headed; the glans seems distinctly bigger … like a medieval soldier’s helmet, called a sallet”. The third has one that is “small, darkly pigmented”; the fourth – well, you get the idea.

What one might dub the Tiresias mode is strangely popular as a trope for the middle-aged male author, if novels by Sebastian Faulks, Douglas Kennedy, Ian McEwan and William Nicholson are anything to go by. Alas, despite the frankness encouraged by feminism, women’s sexual feelings tend to remain a mystery to them: we do not, I’m afraid, tend to recall the size, shape and particularities of a lover’s penis, only the skill with which it is deployed (plus whether it belongs to someone acquainted with washing). It is men who obsess over other men’s tackle; and the moment Amory gives us the details is the moment most female readers will stop believing in her as anything other than a bloke in drag.

The debatable lands between reality and fiction have been Boyd’s chosen territory ever since The New Confessions (1987), and perhaps the success of Restless encouraged him to describe a similar trajectory with a heroine instead of a hero. As in Any Human Heart, real people (or celebrities) are mixed up with fictional ones, and the fictional passed off as real: the novel’s title, supposedly a quote from a French poet, turns out to be by one of Amory’s lovers, Charbonneau. Amory tells us, teasingly, that she was a “mistake”, because her birth in 1908 was announced in The Times as that of a son; subsequently, her war-crazed father tries to kill her which, given that he’s a failed novelist, sounds like special pleading.

Amory’s account of her life over 70 years, interleaved with a journal being written in old age on a remote Scottish cottage, comprise the novel. As the 20th century by numbers, it moves from comfortable Edwardian Sussex to 1920s London, pre-war Berlin, 1930s New York, war-torn France and, in her sixties, Vietnam: for Amory, enchanted by the camera’s potential to “stop time’s relentless motion”, is a professional photographer.

Boyd is a gifted and intelligent story-teller, who possesses the charm to beguile us through a tale which, like all his novels, bears testimony to the damage inflicted on the human psyche by love and war. Always interested in the visual arts, his choice of photography for his heroine promises much, especially given the fascinating lives of real women photographers such as Lee Miller, and he has clearly done his technical research. We gradually divine that Amory, always looking at others rather than herself, is beautiful as well as posh (she marries into the Scottish aristocracy, which causes her to be addressed, weirdly, as “Lady Amory”). Pleasingly, she is a canny survivor, especially in a crisis. Her hidden camera, with which she photographs the Berlin prostitutes, her snatched pictures of criminal events, and her unconventionality all promise an interesting climax.

Yet her episodic adventures do not amount to a plot, the climax never arrives and her attributes seem less like those of a fully imagined character than those of a shell waiting for a great actress to breathe life into her in the TV serialisation that will no doubt follow. With its echoes of Isherwood’s “I am a camera”, this is clearly a conscious authorial choice, but for the reader it tends to be an unrewarding one, devoid of the empathy which a more emotionally involving creation would command. Only at the end of the novel does it lift into something more moving, revealed to be an account of her life as “a long preparation” for mortality, to which, after all her chance escapes from death, she wishes to come by her own hand.

The layers of metafiction added to the narrative do not help either. Amory herself is not just the daughter of a crazed novelist but the subject of her former lover’s roman à clef – or “roman a Clay” as she puts it, wincingly. There are allusions to her being made up in the title of her books (Absences) as in Charbonneau’s Feu d’Artifice. Just to underline the ludic nature of the narrative, blurry photographs purporting to be those of the real people mentioned in Amory’s narrative are included. Presumably their poor composition is supposed to reflect the “unsatisfactory” nature of life.

Photographs may seem striking, but have been used by experimental novelists from Virginia Woolf to W G Sebald to draw attention to the fictiveness of fiction over the past century. It’s not novel: indeed, it’s an affectation that should now be laid to rest. It isn’t entertaining, enlightening or even instructive.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies