The Wandering Falcon, By Jamil Ahmad

The Wandering Falcon's opening chapter appeared in a collection of essays and short stories on Pakistan last year, marking Jamil Ahmad's debut as a fiction writer. "The Sins of the Mother" dramatised a tribal honour killing and was written with such a terrible beauty that its author became Penguin's bright new discovery, at the age of 78.

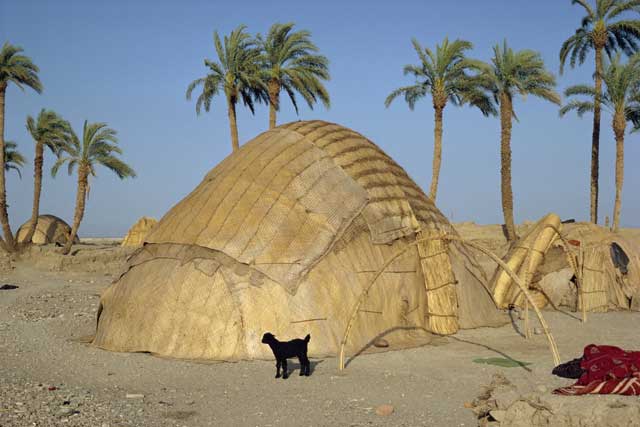

Ahmad had, until his retirement, spent decades in the Pakistani civil service, stationed in the Frontier Province and Balochistan. These territories, which comprise the semi-autonomous tribal belt along Iran and Afghanistan's borders, are inhabited by clans that follow their own ancient "jirga" system of justice over Pakistan's official laws of jurisprudence.

With this novel, Ahmad has followed Mark Twain's advice to write what he knows. And what he knows is all the more fiction-worthy for his lived experience among these hardy people, much feared and little known. Learning the lore of this land, rich in natural beauty and governed by ancient custom and internecine rivalry, appears to have been a lifetime's work for Ahmad. The region itself now becomes the tragic protagonist of this highly accomplished first novel, revealing both its stubbornly unyielding character and the fortunes of the people it crushes in its indefatigable battle against modernity.

The story is set in recent decades, despite the medieval undertones. It begins with the revenge killing of a servant who runs away with his master's daughter. Five years after their escape into the desert dunes, the couple is hunted down. The servant is stoned to death, his young son bearing witness to the justice meted out to those who betray the tribe.

It is this orphaned boy, Tor Baz, whom the reader follows as he wanders nomadically, his personal fortunes criss-crossing with the men and women from the various tribes - the Afridis, Wazirs, Bhittanis, Gujjars and Masuds.There are over-burdened fathers who have forgotten the names of their children, women sold as virgins or whores at market, rebel mullahs, outlaws and once-great tribal leaders whose lion pride has been cut down by old age.

A broader politics of the territory emerges through his encounters – the tribal leaders' historic alliance with the Germans during the Second World War; the Soviet invasion; old enmities against the British.

Tor Baz is no hero, but he is a survivor. As a boy, his fortunes lie in the hands of the men who adopt him. He realises that the frequency with which his adoptive fathers perish reflects the dangers of embedding himself within one tribe, and he learns to align himself with whoever will help him.

An official who cannot pin-down Tor Baz's tribal loyalties asks him who he is: "Think of Tor Baz as your hunting falcon," he answers enigmatically. For the reader, Tor Baz stays distant and unknowable. We see through him the tribes he meets and the laws that govern their lives and deaths.

His psychological opacity chimes with the novel's subject matter - a community led by machismo where people cannot afford to mourn their losses for too long if they are to survive. The simplicity of the narration gives a fable-like effect to the storytelling. Its elegiac voice mourns the lot of the characters, yet refuses to judge the laws that trap them. They are neither romanticised nor vilified, but shown in all their terrible, resilient beauty.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies