Ballet and Opera - The odd couple

To many ballet fans, opera is all about melodrama and inappropriate vocalising. Yet, to opera aficionados, ballet can seem limited and dull. But, Jessica Duchen says, they do work together – and two companies aim to prove it

It's not that the loos at the Royal Opera House are necessarily an ideal barometer of public taste, but attending Wagner's Tristan und Isolde recently, I had a startling experience: it was the only time I have ever noticed a longer queue for the men's room than the women's. But, a few days later, in the interval of a dress rehearsal for the ballet The Sleeping Beauty, there was barely a man in sight. Opera and ballet audiences don't often mix, and it's not only about gender. How many people at each show, I wonder, would have ventured into the other?

Both London's main opera houses are currently finding out, if with very different repertoires. On 20 November the Royal Opera House opens its much-anticipated production of Tchaikovsky's opera The Tsarina's Slippers, with a huge cast and a powerful dance element provided by the Royal Ballet. At the Coliseum, Bartók's one-act opera Duke Bluebeard's Castle is featuring in a double bill with Stravinsky's ballet The Rite of Spring.

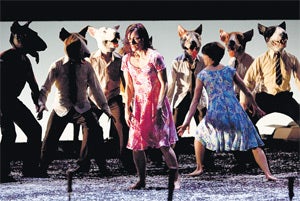

Will the audience for the one art open their minds and hearts to the other? English National Opera's Rite has been radically reinterpreted by the Irish company Fabulous Beast and its choreographer Michael Keegan-Dolan; Bluebeard, directed by Daniel Kramer, has transformed the sinister male lead into a Joseph Fritzl-like figure. Both have drawn rave reviews, plus a handful of noisy dissenters – sometimes from the "other" side of the pale, but not always. Perhaps most importantly, the evening has created huge excitement, evidently chiming with those who enjoy cutting-edge theatre whether in words, song or dance.

For that's where the two genres meet: in their ability to elasticate a musical and theatrical experience, stretching its potential, and the audience's, in different directions. Ballet, when you encounter it for the first time, can stun you with the astonishing capability of the body to express extremes of emotions through movement alone. The revelation of opera at its finest, too, can produce a shock of wonder: can those sounds really come out of a human throat? If an opera or a ballet is staged with maximum theatrical and musical quality, there is theoretically no reason why an audience that already appreciates theatre and music shouldn't respond equally well to both.

The real problem is with preconception rather than reality. A dance fan might hesitate to try Bluebeard in the expectation that it is a "difficult" opera with nothing to watch except a serial killer revealing his house of horrors and inexplicably bursting into song. Meanwhile, straight men, sadly, still often imagine that attending dance is an inherently gay pastime (though straight women do not share that view – Cuban premier danseur Carlos Acosta, for example, is a rather popular pin-up). All manner of prejudices can get in the way. I hesitate to drag my violinist husband to another ballet, because when I took him to The Sleeping Beauty – my ultimate birthday treat – he nodded off within ten minutes, remembering his days in an orchestra pit in Denmark where ballet had meant dull tempi and overhead thumps.

Yet ballet and opera did not always operate on such different circuits. In the mid-19th century, an opera that did not include a ballet by way of divertissement was positively anathema. That was why Wagner's manipulation of the ballet element in Tannhäuser caused one of the biggest operatic scandals in history. The members of the Jockey Club de Paris expected to be able to roll into an opera late, just in time to see their mistresses – the dancing girls – performing in Act II, where the obligatory ballet was always placed. Wagner, abhorring such nonsense, added insult to iconoclasm by positioning his ballet at the beginning of Act I, where those philistines were bound to miss it. The first night in 1861 brought a chaos that even he had not anticipated.

Being spliced into opera as artsy titillation for the gentlemen was far from ballet's origins as a high-class independent art form, developing from the courts of Renaissance Italy through the elaborate spectacles demanded, and participated in, by Louis XIV of France. But ballet's artistic repute suffered somewhat in the mid-19th century, possibly because the floaty fairy-tales that were popular then largely featured indifferent music. Only two have survived more or less intact – Giselle and La Sylphide. It was only when dance united with top-quality scores that it began to regain equal standing with opera and concerts. The partnership of Tchaikovsky and the choreographer Marius Petipa pushed both their arts to new heights; later Diaghilev built on this, envisaging ballet as a Gesamtkunstwerk (universal artwork) with top quality designs, the finest new music and the most exciting, boundary-battering choreography. His commissions included Ravel's Daphnis et Chloé, Debussy's Jeux and Stravinsky's three most famous ballets – culminating in The Rite of Spring and another massive theatrical scandal on its opening night in 1913.

Fine music remained vital to ballet in the 20th century: George Balanchine aimed to make music visible in his abstract choreographies, while the partnership of composer John Cage and choreographer Merce Cunningham sparked a creative thread with a momentum of its own. But opera developed on a separate trajectory. It became rare for ballet and opera to collaborate even when they were sharing a theatre, though the Royal Ballet collaborated with the Royal Opera to provide the Polovtsian Dances for Borodin's Prince Igor back in 1990, which proved quite a hit.

Over the past few years, though, a new rapprochement has involved such artists as Mark Morris creating contemporary dance for baroque opera. Morris's choreography for Purcell's King Arthur at ENO in 2006 was widely adored; there one critic spoke of "opera and dance fans eyeing each other suspiciously across the aisles". Michael Keegan-Dolan's choreography for ENO's Ariodante ten years earlier had brought dance to Handel, to high praise; and the Bollywood moves in David McVicar's award-winning staging of Giulio Cesare at Glyndebourne proved amazingly popular. At Covent Garden last March, a double bill of Purcell's Dido and Aeneas and Handel's Acis and Galatea drew in the Royal Ballet and ace choreographer Wayne McGregor, who gave each character a dancer-double. Dance has helped revitalise the "early" operatic repertoire and to win over many new fans for it.

Still, Tchaikovsky remains perhaps the most natural place to unite ballet and opera; The Tsarina's Slippers promises a feast of both. The coinciding of this production with ENO's double-bill success could indicate that the joining of the two arts is now becoming mainstream: a real Gesamtkunstwerk, a complete art form growing maybe more complete than ever.

'The Tsarina's Slippers' opens at the Royal Opera House on 20 November (020-7304 4000) while English National Opera's double bill continues until 27 November (0871 911 0200).

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies