Tangled up in Bob - Six shades of Dylan

In Todd Haynes' daring new biopic of Dylan, six different actors play the same man. He's not trying to be perverse, the director tells Kaleem Aftab it's just the only way he knows how to communicate

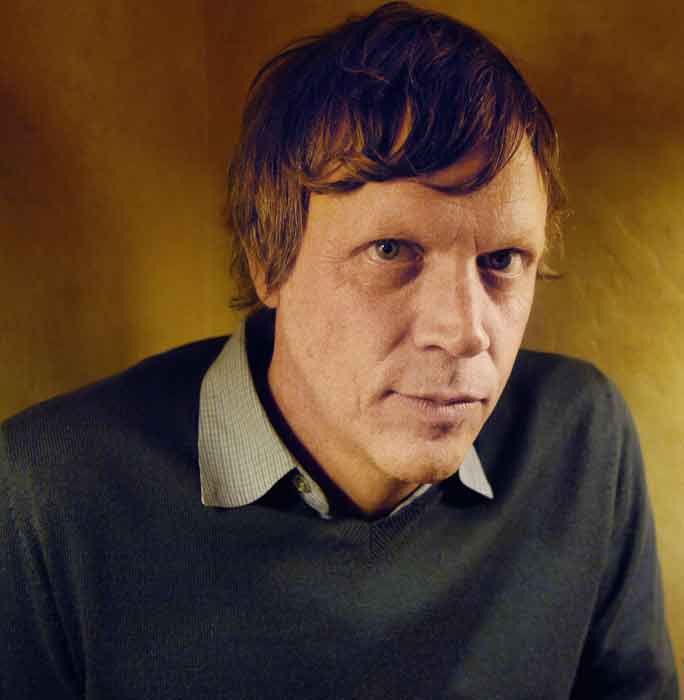

It's easy to feel like you're on a hiding to nothing when you're interviewing Todd Haynes. The 46-year-old has made a living out of films, such as The Karen Carpenter Story and Velvet Goldmine, that demonstrate the near impossibility of capturing a personality in works of art and here I am in a hotel room trying to prod and probe the director with questions that will reveal some deeper truth about him. It would be easy just to talk about Bob Dylan and try to decipher I'm Not There, Haynes's new movie inspired by the life, work and myth of Dylan, but that feels like a cheat, especially as his Dylan picture tells us as much about how Haynes looks at the world as it does about Dylan. Thankfully, it turns out that the director is far more straightforward than his protagonists.

If Haynes were to play Dylan, my first instinct on seeing him is that he'd be the post-motorcycle-crash Dylan, secluded from the public and recording The Basement Tapes while at the same time feeding off stories of anti-Vietnam protests. It's a view that is perhaps influenced by Haynes's decision to start the movie in the aftermath of the mysterious crash, and the fact that the film's title comes from the name of an otherwise unpublished song on The Basement Tapes bootleg recordings. The chicken-or-egg conundrum of whether having seen I'm Not There has in some way coloured my view of Haynes is exactly the type of conundrum that Haynes riffs on.

Haynes's film is not your typical biopic. Six actors play seven different characters, each representing a pivotal time in the folk singer's life and work. The first actor we see is a woman: Cate Blanchett is the post-crash Dylan, but here s/he is dead in the coffin. Haynes says: "'Here lies Bob Dylan, murdered from behind by trembling flesh.' The beginning of the film comes from the first line of a poem that Dylan wrote, sort of as a joke. He's saying, here I am on a slab, everybody take a piece of me, take my phone book, take my numbers, dissect me as you want. I can imagine how Dylan would feel that way at that time; it was jokey and humorous. When the strategy is about regeneration and escaping your old self, death is built into every one of those. I think that he's comfortable with the thought of killing himself off, starting over, and that there are all these corpses left behind."

Haynes burst on to the movie scene in the Eighties, breaking the mould in much the same way that the folk singer did with popular music. His early directorial works, the short Assassins: A Film Concerning Rimbaud made in 1985 and 1987's Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story, in which glove puppets were used instead of actors, fused political and social commentary with philosophical and literary influences, and the resulting break with existing film conventions gave him a counter-culture fan base.

He was especially embraced by the gay community, and was considered to belong to the New Queer Cinema. His film Poison was one of the defining works of the movement, and Safe, starring Julianne Moore, was an allegory of the reaction to Aids. Dylan hated being tagged and I wonder if Haynes feels the same way about the labels he's been given? "No, I really didn't see it [the New Queer Cinema label] as a box," he replies. "Of course, it was a journalist's way of commenting on a series of movies that were coming out at that time. Some people felt it was being forced on us, but I didn't, I actually felt they were right. They were talking about film-makers who were coming out of the Aids epidemic and the activism of the Aids epidemic, and these films all of a sudden had to be made."

Haynes's first foray into popular film-making, Velvet Goldmine, took allegory a step further, and ended in critical and commercial failure. His reaction was to pay homage to Douglas Sirk with the exquisite Far From Heaven. It was Haynes proving that if he wanted to make classical cinema he could do so with aplomb.

Haynes studied semiotics and arts at Brown University, but when I suggest that this might have influenced his symbolic style of film-making, he denies it. "I don't believe that symbols exist," he says. "In my student years, I never really studied signs or symbols per se, I was just a student of film and popular culture like everybody. I think the amazing thing about Hitchcock is that his films function in this pure way that everybody can relate to and everybody can understand; then at the same time there is this whole layer to the films in the way they're shot and conceived, the paranoia of the characters and the way that the central characters are made to feel guilty for no reason that everybody gets, but it also allows the intellectuals, the art critics and the film critics, to spend forever going through layer after layer."

It's easy to accuse Haynes of making use of unintelligible Dylan references in an attempt to flirt with the more highbrow contingent of his audience. He begs to differ and doesn't feel that full comprehension of any of his films is necessary for enjoyment, it's more about gut instinct. "Film is a popular art," he says. "It is not a fine art in my mind, or that isn't what interests me about it. It has to work as a whole thing. I don't want myself to be something people think that only certain people can understand. Sure, there are some of my films that would probably fall more into that category than others, but I'm really proud of the ones that can be shared by different groups."

All the same, I'm Not There poses some tough philosophical questions. Haynes has always been beguiled by the poet Rimbaud, a fascination he shares with Dylan, and it is highlighted in the movie through the segment in which Ben Whishaw plays Dylan as the poet. Rimbaud wanted to demolish the idea of a coherent self; in his films, Haynes seeks to do the same he captures Dylan not by telling his story, but by representing different aspects of the singer's personality.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Haynes points out that the internet has made his disjointed narrative more accessible. He argues that he could have cut the film in a linear fashion, to tell a straight story, but this isn't how the modern mind operates. "Audiences are more sophisticated than we give them credit for," he says. "They're always flipping channels on TV and getting little fragments of this movie or that movie. We're reading culture in a very different way, it's not like we have a beginning and end any more. Things are scrambled and the internet has intensified the potential and ability for people to be canny readers of culture."

Haynes the interviewee is emerging as an affable chap, charming and self-deprecating. He says: "I wish I could be an interviewee like Dylan was and come up with these crazy responses. People would always think he wasn't answering questions and was being elusive, but when you look at them he is really answering them, but almost through an act of performance or some divisive way that makes it even more cool or surprising. I don't have those skills."

I'm just relieved that Haynes is more rooted and obvious in the things that interest him than his musical subject, and that those interests lead to his films.

'I'm Not There' opens on 21 December

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies