Gods & mobsters: the story of an East End 'enforcer'

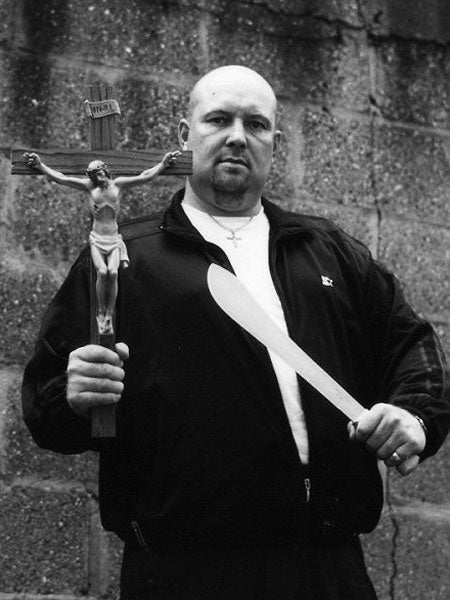

John Pridmore was an East End 'enforcer' who found God, joined a Franciscan order, and now devotes his life to fighting gang culture. It's little wonder that Hollywood wants to tell his story. By Jerome Taylor

Considering he had nearly beaten a man to death, the last thing John Pridmore expected to hear was the voice of God. A veteran East End "enforcer" immersed in London's violent criminal underworld, he had visited a client who failed to pay up after a drug deal. The subsequent assault was so severe that, as Mr Pridmore drove back home that night, he honestly believed he had just notched up his first murder.

The man, though beaten to a bloody pulp, survived. Mr Pridmore was charged with grievous bodily harm. Two weeks later, God came calling. "It seemed like a totally normal night," says Mr Pridmore, who used the crack cocaine he handled. "I was sitting in my chair, thinking about that man when it happened. I suddenly became aware of a voice speaking to me and I knew that it was real and that it was God. I fell to my knees and prayed for the first time and it felt incredible. I've taken every drug there is but the feeling I had that night was the best I have ever felt."

Standing more than six feet tall, with huge shoulders and the obligatory hard-nut's shaven head, the 43-year-old still looks more gangster than godly. But the softly-spoken reformed thug is one of Britain's most unusual and prolific Catholic evangelists.

There is now talk of a Hollywood biopic of Mr Pridmore's life, with the devout Catholic actor James Caviezel, star of The Passion of the Christ, rumoured to be interested in playing God's gangster.

For Mr Pridmore, who flies out to Los Angeles this month for talks with producers, Hollywood is an annoying but necessary diversion. His real passion is talking to children who are lurching towards or have already begun following the violent path he walked.

"Because of my background, I'm able to break all the illusions surrounding gangsterism," he says, speaking from Sydney. "There is a really palpable glorification of the gangster ethos and I try to break that by telling people there is simply no pleasure or grace in violence.

"Our children are obsessed with the glamour of the gangster lifestyle but when you are beating someone who is screaming for mercy I can tell you there's not a lot of glamour in that."

Mr Pridmore's existence once revolved around fast cars, sex, drug deals and money, but he has since renounced worldly goods. After his conversion in 1992 he made his way to the Bronx to join the Fransican Friars of the Renewal, a small group of men who adopt the lives of monks but live in some of the seediest urban districts.

"The work they do is frontline stuff," Mr Pridmore says, talking of the difficulty of adjusting to the strict regime of prayers and charity. "You're working with pimps and prostitutes, bathing homeless guys, helping out in the crack dens, you name it." He has founded his own commune in Co Leitrim, Ireland. When asked who has joined him there, he laughs. "It's a mixed bunch of people who have signed up to five years' service. One of them is a nurse; she's never done anything bad in her life."

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Mr Pridmore, born and brought up in Walthamstow, east London, remembers a perfectly ordinary childhood until, at the age of 10, he was asked to choose between his policeman father and his mother during their acrimonious divorce.

"Some kids can deal with those sorts of situation well but I didn't," he says. "I fell apart and that day made a conscious decision not to love any more."

His father and new step-mother beat him relentlessly, and his teenage years revolved around a series of burglaries and thefts that, by the age of 19, had landed him in a youth detention centre. Later, in prison, he spent most of his time in solitary confinement after frequent fights with fellow inmates.

"When they let me out I was like a caged animal that had suddenly been released. It wasn't long before I found my natural calling."

He gravitated towards London's gangster-owned West End nightclubs, where he "bounced" for a time before moving up the ladder to start running errands for the crime lords he admired.

"I fell in with a crowd of guys who, in my eyes, had everything," he says. "They ran huge drug-importing businesses, protection rackets and most of the West End nightclubs. My first job was to go down to Dover, pick up a Land Rover from a car park and take it back to London. They paid me five grand for that single job. I knew it wasn't exactly Mars bars in the back of that trunk but what did I care?"

As the violence increased, Mr Pridmore never left home without his customised long coat containing special pockets for a machete and a can of mace. "It was a very weird life," he recalls. "I'd be sitting on my sofa, watching Little House on the Prairie with tears streaming down my cheeks. Later that afternoon I might have been practically beating someone to death. It was like the two sides of me never met."

The doubts set in only after the near-fatal assault. "I drove away from that beating and I realised that I felt nothing, no emotion whatsoever. That, in turn, made me start asking myself what exactly I had become.

"On the outside it looked like a glamorous way to live. I had the penthouse flat, the girls, the sex and the sports car. All the things kids today long for. But I was utterly empty inside."

Leaving the gangland fraternity was not easy. Deeply involved in major drug deals and intimately acquainted with the inner workings of London's criminal underworld, Mr Pridmore was afraid he would never be allowed to quit. The only safe way to do so would be to get one of London's crime lords to offer protection and, much to his own surprise, his boss did exactly that.

"He had no need to do it but he believed me," he recalls. "I suspect letting me go was something of an insurance policy, a way of having something to show for himself just in case he needed to explain himself to The Man upstairs."

If and when Mr Pridmore meets his God, he can at least now testify to spending as many years spreading His word as he spent living in sin.

"I suppose my work now is partly driven by a desire to atone for my previous sins," he admits. "That was certainly very much the impetus in the early days, but the more you preach and spread the word the more you learn to love it. It becomes a joy to do."

When he returns from the US later this summer, Mr Pridmore intends to continue talking to young gang members in Britain.

"The message is simple," he says. "I tell them that if you carry a knife, you will either use it on someone or have one used on you. Kids talk to me about protecting themselves with knives but if you're not in a gang then you don't need the protection in the first place."

The Big Man upstairs would no doubt mutter his agreement.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.