In The Valley of Elah, 15<br />The Savages, 15

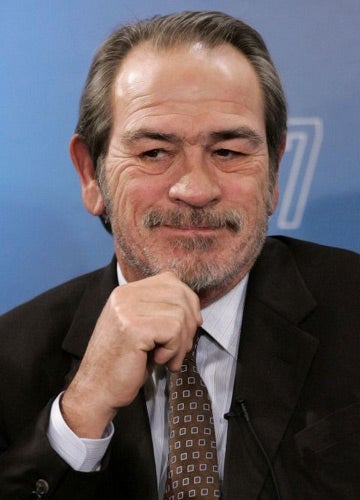

Craggy face meets creaking plot

On Tuesday, Tommy Lee Jones was nominated for an Oscar for his lead role in In The Valley Of Elah, and deservedly so. It might not have been a stretch for him to play a sturdy but weary authoritarian – he did the same thing last week in No Country For Old Men – but he's never had more gravity, and that crumbling monument of a face is so characterful that it's an argument for banning Botox.

He plays a retired military policemen who hears that his son has vanished from an army base after completing a tour of duty in Iraq. Jones sniffs around for any trace of him in the nearby desert town. There's a chance that his son is involved in drug smuggling, or some other crime, so the army is reluctant to co-operate, and Jones has to rely on Charlize Theron's policewoman to help.

Theron, meanwhile, has to contend with the sexism of her fat, male colleagues – just one of the clichés in a laboured, humourless drama that puts issues ahead of originality. Itbegins ponderously, with a palette of washed-out blues and browns, and it gets ever slower as the mystery creaks toward its solution, and Paul Haggis, the writer-director, weighs it down with more and more political speeches about how stressful it is to be a soldier in the United States. His politics aren't quite as liberal as he seems to think, however.

Speaking up for under-trained, under-equipped troops is one thing, but it's obnoxious of him to imply that, when Iraqi civilians are tortured or killed by Americans, it's the perpetrators we should feel sorry for.

The Savages has had Oscar nominations for its screenplay and for its lead actress, Laura Linney. The film follows The Squid and the Whale and Little Miss Sunshine as this year's nuanced indie comedy drama about a screwed-up, middle-class family featuring one literature professor. It's sadder than both, though.

Linney and Philip Sey-mour Hoffman star as a sister and brother who rarely see each other, and who see their elderly abusive father, Philip Bosco, even less. He lives in Arizona's Sun City – Stepford for wrinklies – but the onset of dementia forces his children to install him in a nursing home near Hoffman's house.

Instead of having a neat, cathartic plot, Tamara Jenkins' film is a series of anecdotes – unsentimental, uncomfortably funny, but always wise and sympathetic – about the indignities of the situation, and the contrasting ways the characters deal with them. Hoffman would prefer to be working on his Brecht thesis than tending his dementing father, while Linney treats his illness as a much-needed opportunity to take control of someone's life, because she can't take control of her own.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies