My first psychobilly gig: The Klub Foot, The Meteors, and a thousand DMs

The combination of rockabilly and punk was all that mattered to a teenaged Lois Pryce. It was a genre defined by swearing, sneering and potentially fatal dance moves – so she couldn't believe her luck when her mother allowed her to go to her first gig

I was turned away from what should have been my first gig, thanks to a diligent bouncer adept at identifying underage girls beneath their layers of Constance Carroll make-up. It was The Housemartins at Bristol's Studio nightclub in 1986, I was 13 and their feelgood hit "Happy Hour" was bopping up the charts. Although piqued at the time, I am now grateful to that conscientious doorman. A lot can happen in a teenage year and by the time I did see a live band, my musical tastes had moved on from Paul Heaton's chirpy pop to a far more exciting genre: psychobilly.

Although currently enjoying a revival in Europe and the US, psychobilly is not a musical movement that time has judged kindly. A mash-up of 1950s rockabilly and 1970s punk with a horror B-movie aesthetic, it was loud, lairy and silly, which is hugely attractive when you're a loud, lairy, silly 14-year-old. Deliberately eschewing both the political agenda of punk and the fussy rules of the rockabilly revivalists, psychobilly was all, and only, about having fun.

There is much debate as to who invented it, but as with all musical genres there were a few pioneers independently experimenting with similar ideas at around the same time. In late 1970s California The Cramps were creating an alchemic new sound, inspired by obscure 1950s rockers and 1960s garage-punk, but here in the UK it was the London trio The Meteors who broke away from the purist rockabilly scene of the early 1980s and stomped a whole new subculture on the musical map.

As the inevitable flood of bands jumped on the wagon, The Meteors were quick to stake their claim as the originators, and coined themselves a mantra, "Only The Meteors are pure psychobilly", which they would snarl from the stage. Their singer and guitarist, P Paul Fenech, was the archetypal angry frontman, whose scorn for the audience only added to his mystique. He played guitar like he'd made a pact with the devil, wore a necklace of bones and refused to reveal what the P stood for. With their onstage sneering, swearing and blood-spitting antics, The Meteors possessed the perfect combination of arrogance, danger and charisma required to create a cult of ardent followers, known as The Wrecking Crew. I was enamoured. The Housemartins and their "Happy Hour" could kiss my ass. Now I was a psychobilly.

Trouble was, I was also a 14-year-old schoolgirl. The ill-fated Housemartins attempt had been executed under the ruse of an ice-skating outing, but finding a way to see The Meteors live was going to prove more tricky. They had no gigs coming up in Bristol, as far as I could glean from the flyers and fanzines I picked up in the local record shops. Most of their dates were in London at venues whose names I had bestowed with mythical status – The Hope & Anchor in Islington, The Greyhound in Fulham and, most significantly of all, The Klub Foot in Hammersmith. The last was the Mecca of the psychobilly scene, a regular club night held in the Clarendon Ballroom, a crumbling old Regency hotel/pub on the Broadway.

The Klub Foot had started in the psychobilly heyday of 1982 and had since hosted every band on the scene in a series of epic gigs, often with four or five bands playing per night. These were recorded and released as the Stomping at the Klub Foot series of live albums and I could quote every lyric and liner note from all of them. I studied the covers of the LPs with a mixture of awe and envy, taking in each detail of the group shots of the audience, clearly drunk out of their skulls, playing up to the camera, covered in sweat and tattoos with their insane haircuts and ripped-up jeans, pints of snakebite sloshing wildly as they gurned for the photo outside the legendary venue. Oh, to visit The Klub Foot, to pass through its hallowed doors and feel its sticky carpet beneath my Dr Martens. Oh, to be on the cover of one of those albums, I would fantasise from my bedroom 120 miles away as I patiently painted a logo of The Meteors on to my school-bag. I had been to London only once, and that was to visit Madame Tussauds.

The music press of the mid-1980s didn't give many column inches to psychobilly bands, and when they did get a mention, it was in rather snooty terms, the subtext being that these goons were not to be taken seriously. NME was the worst offender, with Melody Maker a close second; if you read those papers it seemed as though the whole world was in the throes of some giant Morrissey wankfest. Sounds was the only one of the music inkies that would review psychobilly releases and gigs, so it became my weekly purchase and it was in its pages that I first read the terrible news.

The Klub Foot was to close! In what now seems like a portentous warning of what would unfold across London over the following two decades, the Clarendon Hotel Ballroom was to be demolished for the regeneration and development of Hammersmith Broadway. The Klub Foot was hosting a week of gigs to bid farewell to its fabled home. And of course, the final one would feature The Meteors, the originators, the creators, the only pure psychobilly band in the world! My favourite band. I simply had to go.

But how to convince my mum? Slipping away for a couple of Slush Puppies at the local ice rink was one thing, but pulling off an overnight trip to London to see a band of foul-mouthed, blood-swilling quasi-Satanists would test filial relations. Fortunately, I was not alone in my mission; my older brother, aged 15, had also embraced all things psychobilly, and although we engaged in heated teatime debates about The Meteors' best material, he was on board with the plan. I had no idea how my mother would react to the proposition; her parenting boundaries were unclear to my teenage mind. On the one hand, she had allowed me, aged 13, to spend a week cycling around Cornwall with three friends and no grown-ups, and the previous summer had even taken me and my brothers to Glastonbury Festival, where we had watched Half Man Half Biscuit en famille. But on the other hand, make-up was disapproved of, and in only the previous week I had been forbidden from staying up late to watch Rebel Without a Cause. What crazy adult logic was this?

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

I still don't know how or why, but permission was granted – with one caveat. We had to stay with trustworthy adults in London. As far as I was aware, we didn't know anyone in London, trustworthy or otherwise, but some distant family members were rustled up. I'm not sure who they were and I don't think we've ever heard from them since, but they seemed willing to host two unknown teenage relatives who were coming to London for a "concert" – as I overheard my mum describe it to them on the phone. I bought two National Express tickets from Bristol bus station, a can of super-strength hairspray from Boots the Chemist and a bottle of Woodpecker cider and ten Silk Cut from the child-friendly off licence next to my school. I could not have been more excited.

The M4 is a dull drive. Until you hit Junction 2 and the elevated section coming into London and it goes all Blade Runner, with shiny skyscrapers and neon flashing past. I saw a billboard that moved! It flicked round as if by magic, and a different advert appeared. I remember gripping the seat in front of me and thinking, 'What happens next?', almost breathless with the thrill of it all, like anything could happen now. My second thought was pure Dick Whittington, like so many before me. One day, I vowed, I would leave my two-bit home town behind, I would buy a one-way National Express ticket and make London mine.

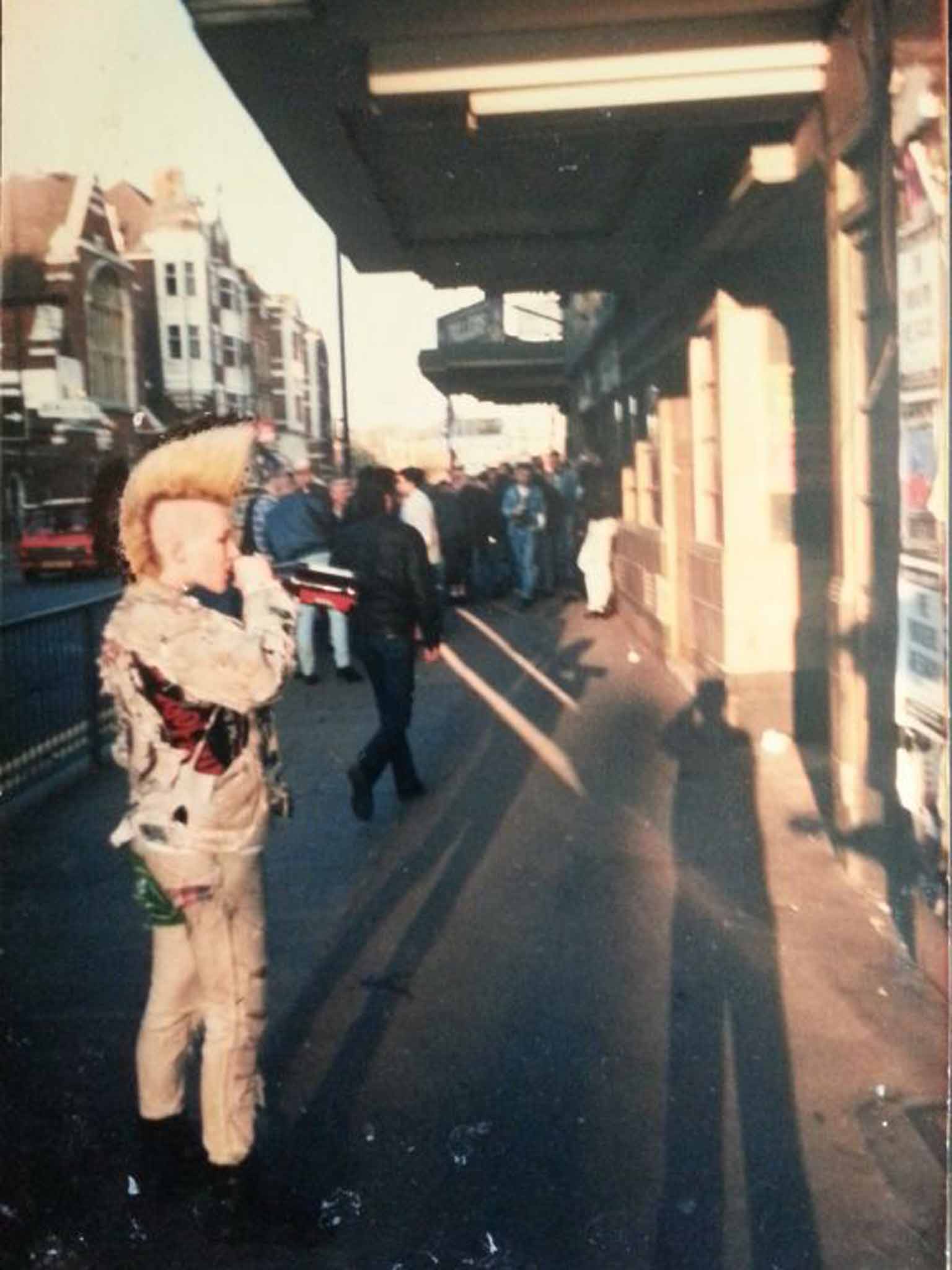

Having no sense of the capital's geography, we didn't realise that as our coach rumbled over another flyover, we were passing within yards of The Klub Foot itself. A Tube journey back from Victoria coach station eventually spat us out at Hammersmith station. And suddenly there were loads of us, all piling off the train. People who looked and dressed like us, bounding up the steps, spilling out on to the street, moving in waves towards the Clarendon. A gathering of the tribe, all come to bid goodbye to our spiritual home. Everyone was singing Meteors songs in unison, cheering, drinking, laughing, shouting. With our monstrous mohawks and quiffs, big boots and ripped clothes, we probably appeared an intimidating spectacle. And although excited, I was intimidated, too; everyone seemed older and cooler and more confident than me. But the mood was good. We were kids and we were out for kicks. Then someone shouted The Meteors' call to arms, the command that P Paul Fenech used to kick off each gig: "Go Mental!" And we obeyed, running down the street in a giant noisy horde.

We had to queue on the pavement outside the Clarendon, which was super exciting because it meant I could live out my record-sleeve fantasy, standing under the sign so familiar to me. I swigged from my bottle of Woodpecker and my brother took a photo of this auspicious moment. Then the doors opened and we all rushed in. The Klub Foot was everything I had hoped it would be. Dark, loud, filthy, a condemned building, long slated for demolition, but nobody who was there that night cared about fire exits or clean toilets. The floors were as tacky as I had imagined, a century of peeling wallpaper was patched with flyers and stickers from a decade of gigs. Every other surface was painted black. Cheap lager and cider rained down all around me. Everybody was up for it.

The gig was spread over two floors: the big ballroom upstairs, which held 900 people, and a smaller room down below. The stairwell between the floors was packed with bodies staggering and sliding between the two spaces. Everyone was already drunk, the place was hot and airless, thick with sweat and smoke. The three support bands whipped up the crowd and by the time the last one bashed out their final chord, the room was rammed beyond capacity. The lights dimmed and the wait seemed interminable. They were keeping us hanging on. People were shouting and cheering, a few bottles flew overhead. The tension was palpable. Then the chanting began… "In Heaven, everything is fine, in Heaven, everything is fine…" the eerie song from Eraserhead, which had been appropriated by The Meteors to open their debut album.

P Paul Fenech, with the savvy of a cult leader, knew that if you gave the people something to chant, you had them in the palm of your hand. The crowd stamped in time, the sprung floor shuddering beneath the impact of a thousand DMs and para boots.

Then, with a flash of the stage lights, three figures appeared before us. A twang of guitar and a volley of abuse blasted from the speakers – and they were off. "Go Mental!"

Short, overweight, balding and obnoxious, P Paul Fenech made an unusual frontman, not to mention an unusual object of hero worship for a 14-year-old girl. It's true to say it was a musical rather than a physical thing; I was enamoured of his guitar playing above all else. But as scientific studies have shown, man plus guitar has an aphrodisiac effect, and Fenech's red-hot licks had sucked me into his vortex. I stood there among the heaving, roaring mass of sweaty flesh, cheering and screaming, singing along. I knew all the words.

Down the front was the "wrecking pit", where something that could loosely be described as dancing was taking place. Unique to psychobilly, wrecking requires no skill but is not for the faint of heart, involving nothing more taxing than standing in one spot with flailing arms, either beating the shit out of your fellow dancers, or getting the shit beaten out of you, depending on your physical strength and bulk. Like everything associated with this music, it was a curious mixture of aggression and bonhomie, with participants holding no prisoners but always ready to scoop up a fallen comrade from the floor. I steamed in and gave it my best shot until I had to admit defeat when I was flattened by what appeared to be a giant slab of tattooed blubber in dungarees. It was probably the most exciting thing that had ever happened to me at that point in my life.

The Woodpecker had kicked in now. I climbed up on the stage and watched the last few songs up close. After several furious encores, The Meteors gave us their final sneer and stalked off stage to the sound of the insatiable audience, stamping and shouting for more. But there was no more. The Klub Foot was over. I snaffled the set list for my scrapbook and my brother and I stumbled out on to Hammersmith Broadway, drunk, battered and overawed.

I followed The Meteors avidly for the next couple of years, hitchhiking all over the country with my brother and our friends, collecting set lists, flyers and bruises, sleeping in train stations, bus stops and abandoned buildings after each gig. But teenage fandom burns short and bright and as my adolescence came to an end, my hair grew back and other sounds made their way into my record collection.

It was 10 years later, by which time my Dick Whittington pledge had become a reality, that I found myself working at a record label in Camden. In the first week, my boss announced he had just made a new signing: The Meteors. We were going to release their next album and, what's more, they were playing a big London gig the following week. As their new label, we would be attending, and naturally, the band had invited us to hang out with them backstage.

Ah, if only my 14-year-old self could see me now, I thought with a smile as we set off for the gig. A lot had changed in the last decade; I had learnt many life lessons and that night I was about to learn one more, the one about meeting your heroes…

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies