New exhibition exploring the changing state of the nation is a curtain-raiser for the election

From Greenham Common to the Troubles, the London riots to mad cow disease, the Hayward’s ambitious new show explores the changing state of the nation over the past 70 years

In 1971, the first women’s refuge in the UK was opened by campaigner Erin Pizzey in a Victorian house on Chiswick High Road, London. This was the era of the second-wave women’s movement, when the personal was deemed to be political, and violence that took place in the private sphere of the home was seen to express wider power structures. The refuge was inundated; there was space for 36, but 120 women and children seeking protection from domestic violence were staying there at one time.

In 1978, the photographer Christine Voge documented daily life in the refuge. Her black-and-white photographs are vivid and moving. One shows a woman gesturing wildly after perhaps dropping fag ash on her flowing paisley-print dress. Or perhaps she is dancing. She stands in front of bunk beds, a recurrent feature of the series: families slept together in rooms decorated with posters of kittens and pop-stars. Voge conveys a sense of intimacy and safety, as well as sadness. Another photograph shows a young mother and her three children sitting on a bunk. Only the toddler looks troubled. He looks wise too.

The series is part of a new exhibition, History Is Now, at the Hayward Gallery, London, which aims to “offer a new way of thinking about how we got to where we are today”. The title is not promising; it sounds like a party conference platitude. Indeed, this exploration of recent British history is designed to orientate us prior to the general election, which likewise doesn’t sound too promising. However, for the most part, it really works.

This is due to the curation. Seven artists have been invited to curate their own sections. Crucially, the Hayward has invited artists who are not in love with the British establishment. There are moments in this exhibition that truly do illuminate where we are now through where we once were.

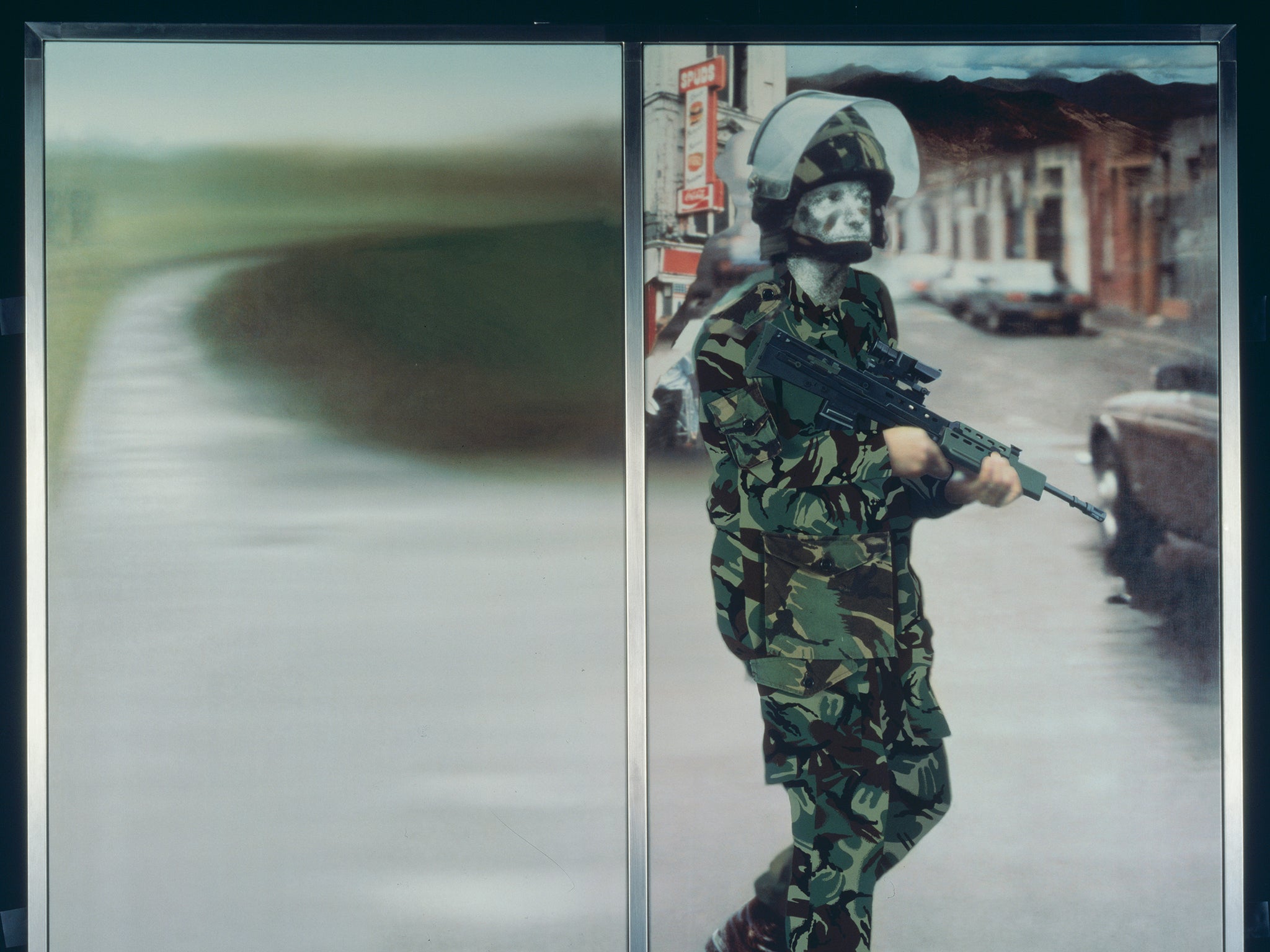

Voge’s series is part of the section curated by Jane and Louise Wilson. Another astounding work chosen by the Wilsons is Northern Ireland 1968 – May Day 1975 (1975-6) by Conrad Atkinson. It is a text and image documentation of the Troubles, from both Catholic and Protestant points of view. The photographs of street graffiti and eye-witness accounts give a sense of the horror and impotence of civilians trapped in violence.

The Wilsons’ section also includes floor-to-ceiling blown-up photographs of Lyn Barlow attempting to climb over and break through the wire fence of RAF Greenham Common. Barlow was a member of the women’s peace camp that became synonymous with the airfield. Here the scale of her defiance of authority is literally and symbolically enlarged by the Wilsons; it assumes the grandeur of the epic.

Hannah Starkey has curated another fantastic section of the exhibition. Among the most affecting photographs is Paul Graham’s Beyond Caring series (1984-6), for which he visited hundreds of social security and unemployment offices around the country. He was appalled: “Rarely did I see acceptable conditions or efficient services.” Instead, he found “humiliation, suffering, indignation, and loss of compassion for those at the most vulnerable end of our society”.

One photograph shows a DHSS office in Birmingham, where people wait silently for their dole money. The strip-lighting and linoleum floor lend a sense of sterile hopelessness. In the centre, a baby in pink stands bemused by what is going on around her. There is tenderness in the image. Another shows a baby in a pram at the end of a long pale-blue corridor of cubicles in the Brixton DHSS office. She appears unbearably alone in a bureaucratic nightmare. The series is indeed relevant to today.

During the Seventies and Eighties, the Arts Council offered invaluable financial support to photographers who were not working commercially. Many of the photographs selected by Starkey come from the Arts Council Collection; in this way, she is celebrating the history of state sponsorship of the arts in the UK.

Starkey is influenced by John Berger’s insistence on the relationship between visual culture and politics. This seems to me the best of Britishness: imaginative critique and the belief that art has a role in society beyond merely pleasing the rich. Possession (1976) looks like an poster ad, but it is in fact a conceptual artwork by Victor Burgin. It shows a glamorous blond woman brushing her lips against the cheek of her lover. Below is a quote from The Economist: “7% of our population own 84% of our wealth”. More than 30 years later, a similar slogan was used by the Occupy movement. Also notable is the slide show Who’s Holding the Baby? (1978) by the women’s art collective, the Hackney Flashers.

Not all of the exhibition is successful. I didn’t like Roger Hiorns’ section, which is entirely devoted to the history of mad cow disease. There seems to be a trend in art at the moment for artists to exhibit an aggressively bland obsession, as though obsessiveness alone were enough to pass for intensity. It seems some artists are trying to achieve a kind of paradoxical state of boring craziness, which is then inflicted on the viewer. Hiorns has included everything from medical equipment to the 1997/8 annual report of “the spongiform encephalopathy advisory committee”. This seems like an exercise in meta-theorising rather than a genuine investigation.

Upstairs, Richard Wentworth has curated a nostalgic and predictable view of post-war Britain, with works by Henry Moore and Ben Nicholson, as well as July, the Seaside (1943) by LS Lowry. The painting points to the typically cold British summertime; most of the people on Lowry’s beach are fully clothed.

Finally, the film-maker and co-founder of the Black Audio Collective, John Akomfrah, has curated a selection of 17 films. They include The Beard of Justice (1994) by Rodreguez King-Dorset, a dance interpretation of the wrongful imprisonment of three men following the death of a policeman during the 1985 London riots. I’m an admirer of Akomfrah’s work and there’s such a wealth of material here; it’s worth setting aside a whole afternoon to see his section alone. Many of the films are an hour long or more.

Overall, the Hayward has done a great job with this exhibition – we are invited to be outraged at the present political system, armed with art, not dogma.

History Is Now: 7 Artists Take on Britain, Hayward Gallery, London SE1 (020 7960 4200) to 26 April

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies