Brave new world: Theatre enjoys a renaissance as state-of-the-nation dramas shine a light on modern Britain

Something strange is happening in the theatre this year. With unprecedented intensity, new plays are telling us about our lives in styles ranging from documentary socio-drama to great apocalyptic statements. Our fears are transformed into hopes in that process of joyful recognition peculiar to the experience of live theatre.

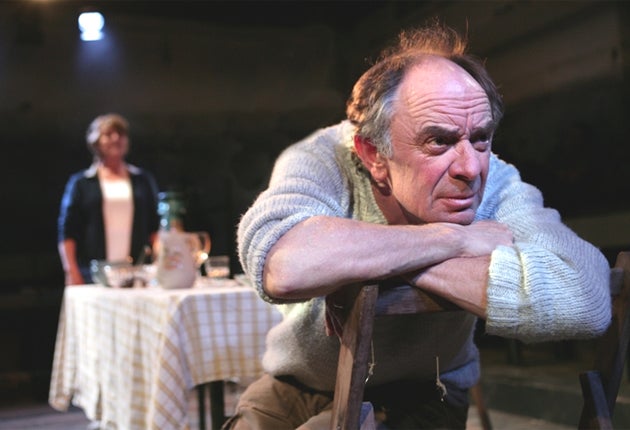

In Jez Butterworth's Jerusalem at the Royal Court, a band of wastrels and stroppy teenagers gather round the mobile home of Johnny Byron in the depths of a Wiltshire forest and listen to his new-age rant about a proposed raid on the nearby housing estate on St George's Day:

"In a thousand years, Englanders will awake this day and bow their heads and wonder at the genius, guts and guile of the Flintock Rebellion. Davey Dean will be on a ten pence coin. Lee Piper will be on a plinth in Trafalgar Square. Tanya Crawley and Pea Gibbons will have West End musicals written for them by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Sir Elton John..."

This speech, with its mock echoing of Shakespeare's Henry V on the eve of the Battle of Agincourt, is delivered by the actor Mark Rylance in a cunning style of cod patriotic fervor and deep-seated mystical conviction. Johnny has seen the way the world has gone and wants to awaken the giants of the plain and the ghosts of the hinterland. The nation needs re-birthing.

It's this sense of a civilization wearing itself out that makes Butterworth's play so powerful: capitalism has collapsed, the nation is in debt, the pop and television culture is vapid, the politicians discredited, the local authorities despised.

As in the early 1970s, the recession is turning into a real spur for the theatre and, unlike during that earlier period, television is lagging far behind in the drama stakes. Even the new back-catalogue pop show, Dreamboats and Petticoats, is tuned to the zeitgeist: the biggest reaction of the night comes when a father advises his son that, "It's no good living beyond your means; if everyone did that, the country would go bankrupt."

When the National Theatre opened its doors on the South Bank in 1976, one of longest-running poster campaigns proclaimed, "The National Theatre Is Yours". Nobody really believed that. But in the current climate, aided by the astute programming of artistic director Nicholas Hytner, it's almost as if we turn to the NT for assistance in deconstructing our contemporary woes, just as the Greeks did in the ancient theatres of Athens.

Hanif Kureishi's The Black Album, which has just entered the NT repertoire, may not be the greatest production of all time, but the author's adaptation of his own novel, written some years after the fatwah delivered to Salman Rushdie, now seems positively prophetic in its analysis of the seeds of unrest and terrorism in urban Muslim communities of students and competing ideologues (and, for that matter, in its incidental portrait of a stuttering white Marxist who acquires another syllable on his impediment each time a communist state collapses in Eastern Europe).

The Black Album is in some ways complementary to Richard Bean's England People Very Nice, still playing in the National's repertoire, which anatomises in comic-cartoon fashion the history of immigration in this country in order to get to the point where Bean can sell the sizzle of Muslim hooligans in the East End of London without being accused of racialist partiality (although he was, of course, accused of precisely that).

Bean's savagely critical and satirical approach to the state we're in would have been unthinkable in the subsidized theatre of 30 or 30 years ago. The popular misconception that theatre should be more concerned with escapism than the real-life experience of an audience looks in tatters, and David Hare's "Defence of the New," 1996 lecture more than out of date.

Hare said then that, "It is hard to understand why anyone would choose to go into the theatre in the first place unless they were interested in relating what they make happen on a stage to what is happening off it." You might still find something in Hare's criticism of the Royal Shakespeare Company abandoning its original aim of producing the house dramatist in the context of new work on its large stages, but the case of the RSC has become almost anomalous in any overall discussion of contemporary theatre.

Instead, it's the National and the Royal Court, the Bush and the Almeida, that are holding our lives and times up to scrutiny. In September, a new play by 28-year-old Lucy Prebble, Enron, will open at the Royal Court having already garnered unanimous critical acclaim at the Chichester Festival Theatre. The play is a Brechtian epic about the tragedy of capitalism in the wake of the destruction of the Twin Towers in New York.

Enron is an American story, of course, but the demise of the seventh-largest corporation in the world in the scandal of building ever-larger wealth with wealth that didn't exist in the first place, the fantastical farce of paper money being just that, as though corporate capitalism was no different from a board game, sums up everything that's happened in our own economy.

And nothing the politicians tell us about that economy, or indeed the perils of climate change, carries as much force or conviction as a good play in the theatre. Jerusalem and Enron are undoubtedly the plays of the year so far. But there's a third that was less trumpeted when it surfaced at the Bush Theatre in west London two months ago.

Steve Waters' The Contingency Plan was in fact two fine full-length plays for the price of one, conjuring a vision of Britain submerged in floods and floating to oblivion. The cover of the published text shows Tower Bridge disappearing under the waves of the Thames.

The aptly named Waters' hero, Will Paxton, is a glaciologist advising a newly elected Conservative government on what he terms the coastline catastrophe. While the Met Office witters on about high winds and choppy waters, and politicians grab the opportunity of reinforcing the spirit of D-Day and the resilience of family values, Will outlines his long-term proposals:

"Demolish all houses that are not carbon neutral. Convert all of East Anglia to wetland as a protective sump. Carbon rationing universally applied. One car per street. Cease road construction; in fact, begin to close roads. Gear all farming land to local food production and move towards zero imports. Restructure the economy to local goods and services."

There's undoubtedly a growing realisation that in these drastic times only drastic measures will do, and that's where the theatre comes in to expand the arguments, analyse the problem and propose the alternative solutions to those meekly proffered by today's political parties, who only really care about being elected as opposed to telling or facing the truth.

Censorship used to assist in this policy of repression. In 1737, Henry Fielding, described by Bernard Shaw as the greatest practising dramatist, with the single exception of Shakespeare, produced by England between the Middle Ages and the 19th century, set about exposing in the theatre the rampant parliamentary corruption of the day.

The government promptly gagged the stage by a censorship act that was kept in place until just over 40 years ago. Fielding became a great novelist instead, and English drama withered. Now, thanks partly to Shaw's example, and certainly to the end of censorship, new critical plays are at the heart of our theatre culture and we are entering a second post-war golden age of new British playwriting in the wake of Harold Pinter, John Osborne, Arnold Wesker and Hare's own generation.

At such a time, with many of these plays at last acquiring the epic scale and complexity of the Elizabethan and Brechtian theatres, Shakespeare, too, is rediscovered: the Jude Law Hamlet, the RSC's new Julius Caesar and the Globe's current Troilus and Cressida – in which the occupying Greek forces in Troy have forgotten why they went to war in the first place – have all surprised and delighted audiences with their poetic discussion of political systems and tyrannies.

Shaw, too, sounds suddenly fresh. Peter Hall, the founding director of the RSC in 1960, has just revived The Apple Cart in his annual summer season at the Theatre Royal in Bath. One of the craven cabinet ministers in a Scottish Prime Minister's government is done up to look and sound exactly like Hazel Blears, while another is a dead boring ringer for Geoff "Ho-hum" Hoon.

The main drift of The Apple Cart, though, is not so much one of political satire as a serious and fundamental debate on the weakness of elected politicians in the face of a constitutional monarch who is far more in touch with the people than they are. It's a stunning reclamation of a play that has usually belly-flopped in the West End with star names playing the roles of a king and his mistress first written for Noël Coward and Edith Evans.

It's the times themselves that do this to plays, and as we sink in a quagmire of despair and anxiety about the way the world is going – along with our savings, our values and our belief in the ability of politics to change anything – theatre is reanimated as a sounding board in the rising tide of our increasingly important and angry national debate.

'The Black Album' is in repertoire at the National Theatre until 7 October and will then tour the country

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies