Theatre review: Bracken Moor by Alexi Kaye Campbell is an uncanny ghost story about grief

Tricycle Theatre, London

Alexi Kaye Campbell's new play is set in 1937, with Britain struggling to emerge from the Depression, in the grand, wood-panelled Yorkshire home of Harold (Daniel Flynn), a prosperous middle-aged landowner who is now feeling the pinch.

It begins with a dispute over pit closures with the foreman of his mines (Antony Byrne) and the magnate's rejection of a mooted, compromise plan by the workers that would save jobs. By the time this pair confront each other again a couple of days later at the end of the play, Harold will have undergone a potentially life-changing experience such as might unsettle the values of the most die-hard capitalist.

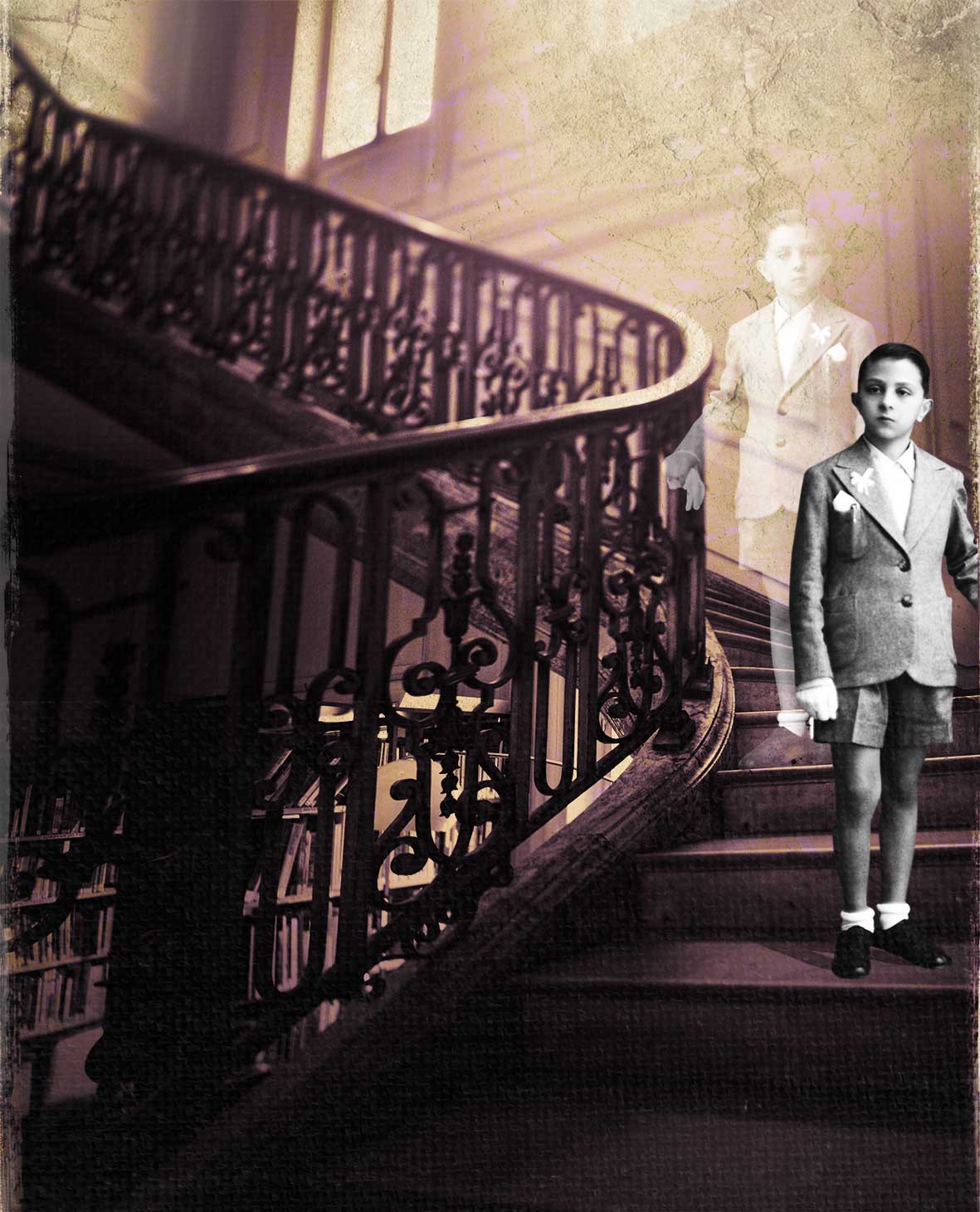

What unfolds in the body of the piece, which is premiered in a cannily uncanny and forcefully acted co-production with Shared Experience by Polly Teale, is a ghost story about grief.

Kaye Campbell, formerly an actor, made his name as a dramatist with The Pride, an acute play about the social position of gay men over the decades. In Bracken Moor, he has produced what feels like a conscious throwback to the J.B. Priestley of An Inspector Calls and Time and The Conways – works in which an otherworldly sense of alternative possibilities puts hidebound political assumptions in the dock.

Helen Schlesinger is hauntingly inconsolable as Elizabeth, the magnate's wife, who has been a spectre-like recluse since the tragic death, ten years previously, of Edgar, their twelve-year-old son. The past is brought back in more ways than one, though, by a visit from a well-meaning, amusingly conventional family (excellent Sarah Woodward and Simon Shepherd) with whom they used to be great pals. Their boy, Terence, had been the dead child's closest friend (and perhaps, it's hinted, incipiently something more). Compellingly portrayed by Joseph Timms, he's now a charming, rather old-headed young man, fresh from a month's retreat on Mount Athos and much given to sententious pronouncements about how the mystical side of man's nature has been warped in the age of the machine.

Then, Terence starts having fits, and talking and acting as if possessed by Edgar's spirit, resurrecting intimate, father-challenging details that only the boy and his mother could have known. Schlesinger is heart-breaking in her desperate, fragile but implacable need to communicate and to make amends through this spooky proxy.

The purported explanation of the phenomenon is, to my mind, emotionally dissatisfying, but the production, with its almost self-parodic lightning flashes, things-that-go-bump-in-the-night quality and committed performances, manages to effect a striking balance between melodramatic form and supernaturally-tinged social message.

To 20 July; 020 7238 1000

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies