The Big Question: How do we balance conservation with the interests of the fishing industry?

Why are we asking this now?

Because we have learned from a BBC correspondent who boarded North Sea trawlers that thousands of tonnes of dead fish are being dumped back in the sea because the boats have reached their EU quotas. The EU estimates that between 40 and 60 per cent of fish caught each year is thrown over the side.

Yesterday, the Fisheries Minister, Jonathan Shaw, described the dumping of this discard as an "absolute waste" and called for the annual cod quota for the North Sea to be raised. This would allow fishermen to land more of their catch and end the waste, he said. But there is a reason why the EU has a low quota for cod – Britain's favourite fish has been almost "fished out" of the North Sea.

How low are our cod stocks?

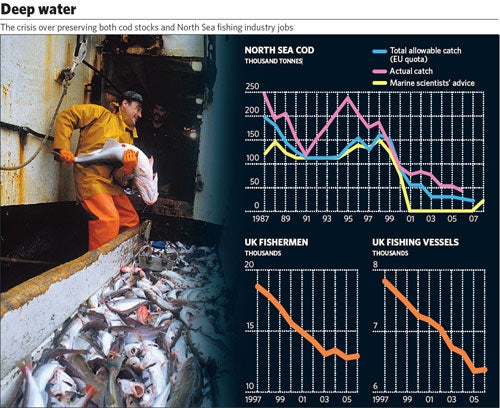

Tiny, by historical standards. In 1980, fishermen were landing 600,000 tonnes of cod from the North Sea. Last year, the catch, including estimated discard, was 44,000 tonnes – 7 per cent of the peak and almost double the EU quota. For the past six years, the International Council for the Exploration of the Seas (ICES) in Copenhagen, the scientific body that advises the EU, has recommended a total ban on cod fishing in the North Sea.

Each year at their annual quota round in December, fisheries ministers, under pressure from their domestic fishing industry, have ignored the advice. But they have reluctantly cut quotas. Last month ICES said the cod stock had improved because of the reduction in fishing, but warned that numbers of juveniles were still only half their long-term average. For the first time in seven years it recommended limited fishing, a quota of 22,000 tonnes.

Why don't we just go and fish elsewhere?

We do. If we didn't, we wouldn't have enough cod to go around. According to the industry authority Seafish, only two per cent of the world's cod now comes from fishing grounds in the shallow North Sea.

Most of the cod we eat in Britain comes from the Barents Sea north of Scandinavia, where it is under increasing pressure, and from Iceland, where stocks are better managed. Fish from Iceland is frozen on board, rather than being fresh like that traditionally landed at UK ports and served as fish suppers. Cod's decline mirrors the decline of fish species around the world.

Are we really running out of fish?

Yes. The Food and Agriculture Organisation says that nearly 70 per cent of the world's fish stocks are now fully fished, over-fished or depleted. A study in the journal Nature in November warned that, unless action is taken, the 21st century would be the last century of wild seafish. By 2048, the scientists warned, stocks would be exhausted.

Between 1993 and 2004, the global catch declined by 14 per cent despite the introduction of larger vessels and better technology for tracking fish. The research leader Boris Worm, from Dalhousie University in Canada, remarked that, having eaten one third of the world's fish stocks, the world was now working its way through the remaining two-thirds.

Today, for instance, the WWF will warn that stocks of bigeye tuna are joining their cousin, the bluefin tuna, in being excessively fished. Once plentiful, cod in the North Sea, Celtic and Irish seas could be exhausted sooner than many think, say environmentalists, who point out a depressing precedent.

The Grand Banks off Newfoundland, Canada, once swarmed with cod so large that it was said you could step on them to reach the shore. In 2002 the fishery was closed because the cod had been "fished out". It remains closed to this day.

In The End of The Line, a chronicle of the predictable and quantifiable disaster befalling the oceans, Charles Clover, the environment journalist, wrote: "The fate of cod in EU waters is an example of history repeating itself."

Some 250,000 tonnes of cod were being caught in the North Sea as recently as 1995, but within six years that figure had dropped to 80,000. Now it is down to under 50,000.

What should we do with the cod in the North Sea?

Perhaps we should follow the recommendation of the scientists and ignore the pleading of the £1bn-a-year British fish industry, no matter how devastating a halving of the cod quota would have on fishing communities. Alternatively, we might change the quota system. Iceland, which is outside the EU, has a system of tradeable catches. This means that if skippers catch more of a particular fish, they can buy a quota for that species from another trawler owner. The creation of a marine reserve, a no-catch zone off Britain, is another idea.

What other solutions are proposed?

The Government intends to publish a draft Marine Bill by Easter, setting out plans for a series of marine-conservation zones, but it is not clear how stringent the controls on fishing will be. Greenpeace favours a new system based on limiting the number of days that trawlers can go to sea, a reduction of the fleet and the creation of marine reserves. Environmentalists are sceptical that politicians have the will to save fish, remarking – as one lobbyist did recently – that the position is unlikely to change until fish get the vote.

And what can consumers do?

Taking an interest in fish is the best thing. For as long as politicians can ignore marine science, the prognosis for stocks will be gloomy. Practically, shoppers can choose white fish under less pressure than cod. The Marine Stewardship Council certifies sustainable pollack from Alaska and hoki from New Zealand.

Closer to home, there are dozens of abundant fish that seldom make it onto the plate such as herring, mackerel, dab, gurnard, flounder, and sardines. The Marine Conservation Society, Britain's biggest marine charity, has a list of fish to eat and fish to avoid on its website – www.fishonline.org. Waitrose and Marks & Spencer top its list of supermarkets for sustainable fish.

Ask the fish counter or fish and chip shop where their supply comes from and if it is sustainable. Farmed fish are fed on pellets made of wild fish, so are not the answer and are a poor substitute for wild fish in any case.

Should we ban fishing for cod in the North Sea?

Yes...

* Cod stocks have dwindled to less than 10 per cent of their peak in the North Sea. The overall trend is for the irreversible disappearance of edible fish from the world's waters

* Halting the catch would allow the juvenile stock to spawn so that one day trawlers may return. Reduction in fishing in recent years has shown the extent to which fish can recover

* Fishing boats have been exceeding their EU quotas for many years and must be brought into line

No...

* Some fishing should be allowed now that cod stocks have staged a minor recovery. Even the marine scientific experts have accepted this

* Cod is caught when trawlers fish for other species such as prawns and should not be wasted. At the moment a huge amount is being returned to the sea

* Ending all fishing would devastate communities in Scotland and eastern England that depend on cod

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies