The Big Question: Are relations between the US and Cuba finally beginning to thaw?

Why are we asking this now?

This weekend Barack Obama and his fellow hemispheric leaders (minus, of course, President Raul Castro of Cuba) gather in Trinidad and Tobago for the fifth Summit of the Americas. Officially, Cuba is not on an agenda focused on the global economic crisis.

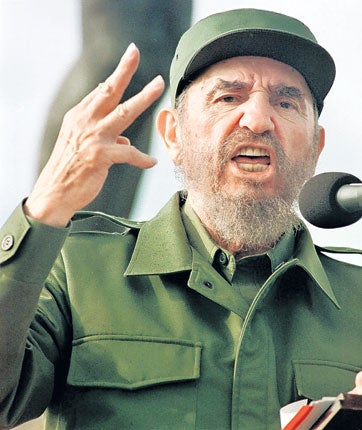

Unofficially however, Cuban-US relations will figure prominently, and circumstances have not been more propitious for change since the trade embargo and travel restrictions for US citizens were imposed in the early 1960s. The Castro era is drawing to a close (Fidel is 82 and in poor health, while Raul is 77). In the US, a highly popular president has come to office promising a "new strategy" towards Cuba. None other than Fidel asked a US Congressional delegation visiting the island last week, "How can we help President Obama?" Equally important, a broad bi-partisan coalition exists on Capitol Hill that believes it is time for a different approach to Havana, after 50 years of a policy that has failed in its objective.

That objective being to return Cuba to the capitalist fold?

Indeed. At first the US tried military force, with the fiasco of the Bay of Pigs operation in 1961. A year later came the Cuban missile crisis. Thereafter the CIA launched a variety of schemes – including enlisting the Mafia and trying to kill Fidel with poisoned milkshakes and exploding cigars. But the Castros have seen off 10 US presidents, from Dwight Eisenhower to George W Bush, and there is no sign that their grip on power is weakening.

What does the rest of the world think?

For half a century the US has sought to isolate Havana, but has only managed to isolate itself. Every year the United Nations General Assembly adopts a non-binding resolution urging Washington to lift the embargo. In the 17th such vote last October, the resolution passed by its widest ever margin. Only Israel and Palau supported the US and 185 countries voted against, including all Washington's major allies. Why, they argue, is the US so unbending on Cuba, when it deals with several other regimes that are scarcely more democratic and have almost as abysmal a human rights record?

They also note the absurdity whereby it is easier for an American citizen to travel to North Korea or Iran than the 90 miles separating Florida from Cuba. A particular irritant is the 1996 Helms Burton Act passed by Congress, which imposes severe US sanctions on foreign companies that do business with Cuba.

What has the Obama administration done so far?

Initially, the new President moved cautiously. Last month he lifted the most draconian curbs on travel to the island and remittances by Cuban Americans to relatives, imposed by former President George W Bush in 2004. The Treasury has relaxed restrictions on trade-related travel by US citizens (despite everything the US is Cuba's fifth-largest trading partner). Mr Obama is expected to announce a more general loosening of travel before the Summit of the Americas which starts on Friday. In Congress, some of the most powerful senators, including Christopher Dodd, the Democratic chairman of the Banking Committee, and Richard Lugar, the top Republican on the Foreign Relations Committee, are sponsoring a bill that would effectively lift the travel ban in its entirety. In the House a new measure would loosen curbs on agricultural trade (currently Cuba has to pay in advance in hard currency for any imports from the US).

But won't the Cuban American exile community be up in arms?

Surprisingly, probably not. Until recently the conventional wisdom still ran that Cuban Americans were so opposed to Castro that they backed, to a man, the toughest possible US sanctions – and that any presidential candidate who felt otherwise was asking for trouble, given the exile community's concentration in swing states like New Jersey and, critically, Florida. But this is much less true today. Mr Obama carried both states handsomely in November's election, despite his criticism of existing Cuba policy. Some diehards, like New Jersey's Democratic Senator Robert Menendez, the son of Cuban immigrants, are passionately opposed to any outreach. But they are increasingly a minority.

So what exactly has changed?

Basically two things. First, the younger generation feels much less emotionally attached to their ancestral homeland. They plainly do not share the fervid anti-Castroism of their parents. And even these latter individuals were lukewarm at best about the tightening of sanctions ordered by former President Bush, in the name of promoting democracy. The measures reduced visits by Cuban Americans from once a year to once every three years and cut remittances to $300 per visit from $3,000. Many felt they were inhumane and counter-productive, punishing ordinary Cubans but not the leadership, and feeding regime propaganda that all Cuba's problems were caused by neo-colonialist "Yanqui" oppressors. The fiercest opponents of the Communist regime must admit that even the loss of the regime's patron in Moscow was not enough to undo it. After 50 years of a failed policy surely it's time for something different.

What does the US stand to gain from more normal relations?

A good deal – economically, diplomatically and in terms of its global image. A significant and easily accessible market would be opened to US agricultural producers. A thaw with Cuba would, at a stroke, improve US ties with many countries in Latin America, and give anti-American demagogues like Hugo Chavez of Venezuela (which provides vital financial aid to Cuba) one less thing to rail about. It might also reduce Cuba's close economic ties with China, a source of some concern in Washington. Rapprochement would be a simple way, with few complications or drawbacks, for the Obama administration to differentiate itself from its unpopular predecessor. And who knows, trade and economic liberalisation might achieve what half a century of bullying and threats have not, and set Cuba on a more democratic path. Last but not least, US aficionados could once again legally savour a fine Havana cigar.

So what will happen at this week's summit?

A dramatic breakthrough is unlikely. Mr Obama has said he is on a "listening mission", much as he was on his recent trip to Europe, and has signalled the trade embargo will stay in force for the time being at least. His fellow leaders will be anxious to talk about how the hemisphere can fight the global economic recession. But Cuba is bound to intrude. Almost certainly, Venezuela and Bolivia will demand Havana's re-instatement in the Organisation of American States, from which it was ejected in 1962. Jeffrey Davidow, Mr Obama's top adviser on the summit has warned that leaders must not waste the opportunity of progress "by getting distracted by the Cuban issue". But Washington must tread carefully, for all the goodwill the new President enjoys. Refusal to engage on Cuba could turn a gathering intended to set a new course in US relations with Latin America into a unpleasant confrontation.

Should the US normalise relations with Cuba?

Yes...

*The embargo is a Cold War anachronism. It is time for both countries to begin to foster mature relationships

*The current policy is indefensible, hypocritical and counter-productive

*A change might actually promote democracy in the island – certainly isolationism has, so far, failed

No...

*Lifting the embargo would reward the regime for its repressive policies which is hardly a US priority in the Obama era

*It would be a betrayal of the human rights prisoners in Cuba who continue to suffer

*It would be a green light for a new generation of dictators in the region

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies