So much things to say...

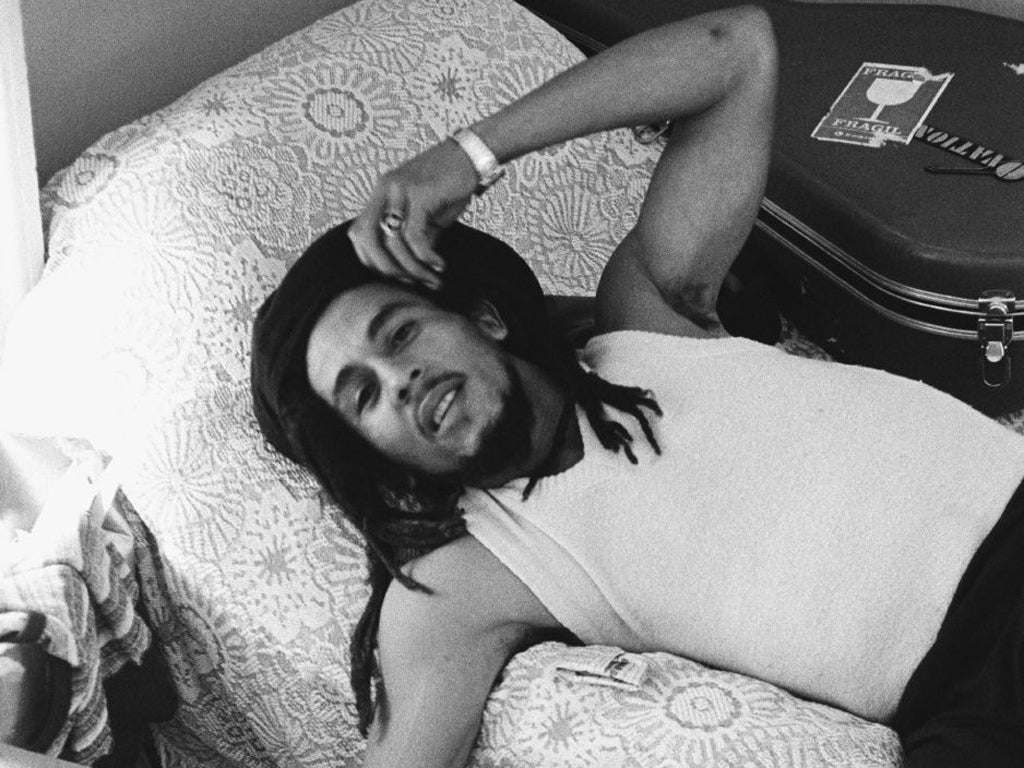

How do you capture a legend like Bob Marley? Let those who knew him talk, says film-maker Kevin Macdonald. By Geoffrey Macnab

When Oscar-winning Scottish director Kevin Macdonald was at boarding school in the Highlands of Perthshire in the early 1980s, he had a passing interest in the music of Jamaican reggae legend Bob Marley and his band, The Wailers. "I do remember that one of the first half dozen albums I ever bought was Uprising," he recalls of Marley's 1980 album. "I remember when Bob died. I remember that news. I would have been 13 (in 1981)."

Macdonald (whose new film, Marley, is released this week) also listened to music from former Wailer Peter Tosh and other reggae artists. "I wasn't an obsessive fan, but when you listen to Uprising, you're sucked in by the melodies, which are so pretty and catchy. It is accessible, but then there is the political and radical element to it. And then there's all that other mystical side."

The youthful Macdonald had no idea who Haile Selassie (the Emperor of Ethiopia) was or why he mattered so much to Marley. Nor did he envisage that he would one day make a film about Bob Marley.

"The way to understand Bob is as the first Third World superstar," the director now says. The fact that he grew up in a one-room hut and slept on a dirt floor is key to who he is and what his appeal is."

On the day I interview him, Macdonald is about to set off to Bath for a special screening of his film at the Little Theatre Cinema – and to discuss Marley's life and career with the poet Benjamin Zephaniah. This was the cinema that Selassie used to visit when he spent the war years in Bath.

It's easy for rationalists to be sceptical about the claims of god-like powers made on behalf of Selassie, the diminutive Ethiopian leader revered as a messiah by Rastafarians.

McDonald explains: " It (Rastafarianism) is a way of saying, 'we don't want to be second-class citizens of Britain or Europe. We want our own identity'. Reaching to Ethiopia is about saying that there's a royal family of our own, and they've got a lineage far longer than anything in Europe."

Macdonald wasn't first choice to make Marley. When American businessman Steve Bing negotiated the music rights for a Marley film, the original idea was that Martin Scorsese would make the movie. Bing's Shangri-La Entertainment had produced and financed Scorsese's Rolling Stones doc, Shine a Light. However, it became apparent that Scorsese's other commitments wouldn't leave him time to complete the project. Enter Silence of the Lambs director, Jonathan Demme, who started researching and shooting the Marley film before stepping aside for reasons which are still unclear.

Bing's window of opportunity to make the film was limited. "He had bought the rights for five years or something," Macdonald recalls. With time running out, he hired the Scot.

Marley's family had been suspicious of previous attempts to make films about the star particularly as it would have been well-nigh impossible to cast the central role. However, by the time Macdonald went to speak to Ziggy Marley (Marley's oldest son "and point person for the family"), they were keen for a documentary to be made. "They felt the people who were talking about Bob and claiming to know about him were representing a Bob they didn't necessarily think was correct. I came to them and said I wanted to make a film about the person."

The film would be Macdonald's quest to discover Marley. The reggae musician's children, especially the younger ones, didn't know their father at all well. They hadn't lived with him.

"They've all said, when they've seen the film, that they've learned a lot about their father. That was a big part of the impulse (in agreeing to the film) for them."

Marley's legacy remains a matter of fierce debate. The documentary makes very clear that neither Bunny Wailer, nor the late Peter Tosh (the other two original Wailers) were happy about the influence of Island Records boss Chris Blackwell on the band.

"Bunny Wailer hates Chris Blackwell," Macdonald notes. "He feels like he took Bob away from Jamaica, like he broke the Wailers up. I don't think it's true, but from Bunny's perspective it is. Also, there is this residual resentment of the white man who has profited to an unseemly degree (as he would see it) from the labour of the black man."

Macdonald is friendly with both Bunny Wailer and Blackwell. He elicits revealing, affectionate and humorous interviews from both. They may have disliked each other, but they both warmed to the film-maker and trusted him to represent their views fairly.

Making a film about Marley is an exercise in detective work as much as of storytelling. Archive material is skimpy and there are fewer photographs than you'd imagine. Many family members and contemporaries have their own partisan view.

Macdonald reacted to the challenges that defeated other would-be chroniclers of the star by trying to be as straightforward as possible.

"I thought, 'I am going to make a very simple film.' I guess it's the most conventional film I've ever made in terms of style. It's about Bob and it's about people talking. It's oral history, I suppose. "

Marley is released on Friday

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies