We're missing the big pictures

Tate Modern has rehung its permanent collection, but the move serves only to expose Britain's lack of 20th-century masterpieces, finds Adrian Hamilton

The two Tates are rehanging with a vengeance now in preparation for their multi-million-pound extensions (£45million for Tate Britain, due to open in next year: £250million for Tate Modern, scheduled to open 2016). The oddity is the two seem to be competing for the same territory. Tate Britain in its recent exhibitions and installations, (Migrations and Picasso & Modern British Art) has covered territory that would have looked just as good and apposite in Tate Modern and indeed might have been rather better done (neither were compulsive or that revealing). Tate Modern in the meantime has chosen to concentrate on temporary exhibitions, many of them in association with other galleries abroad.

That is beginning to change as Tate Modern opens its upper galleries to themed displays of its permanent collections. A new one, grouped around abstract and geometric art of the interwar years, has just opened in the West Wing of the fifth floor. This is to be followed next month by a display of its holding of art from the postwar decades, including its Mark Rothkos, on the floor below. In terms of lighting and space, the new wing, it has to be said, is a success, displaying the works in a series of smaller rooms around a central gallery of height and luminosity. With the fifth floor now fully occupied by permanent collections and the fourth floor soon to be, one at last gets a sense (if you can manage to work out the escalator system) of a modern art museum that is more than one giant hall with a few side bits tacked on.

When it comes to the actual works, however, it becomes rather less impressive. The Tate has not got a great collection of international modern art. You can blame this on the baleful influence of Sir Kenneth Clark, master of the country's taste before the war who took against Picasso and most of Modernism, or the parochialism of the gallery before it got divided into "Britain" and "modern".

But it goes deeper than that. Despite producing a handful of artists of real international status – Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud and Richard Hamilton to name three – Britain remained largely on the margins of the great artistic movements of the 20th century. Relatively few works by Matisse and Picasso entered British collections. Germany hardly figured, nor America or Italy. It was not until the success abroad of the young artists of the Sixties that the country began to wake up to what was happening across the Channel or the Atlantic. The Tate only started seriously buying contemporary art from the Continent in the Seventies and Eighties, too late to catch up on the masters that made modern art as we know it. With limited purchase funds, curators had to rely on either bequests (often in lieu of death duties) and selective buying of lesser known works and lesser known artists.

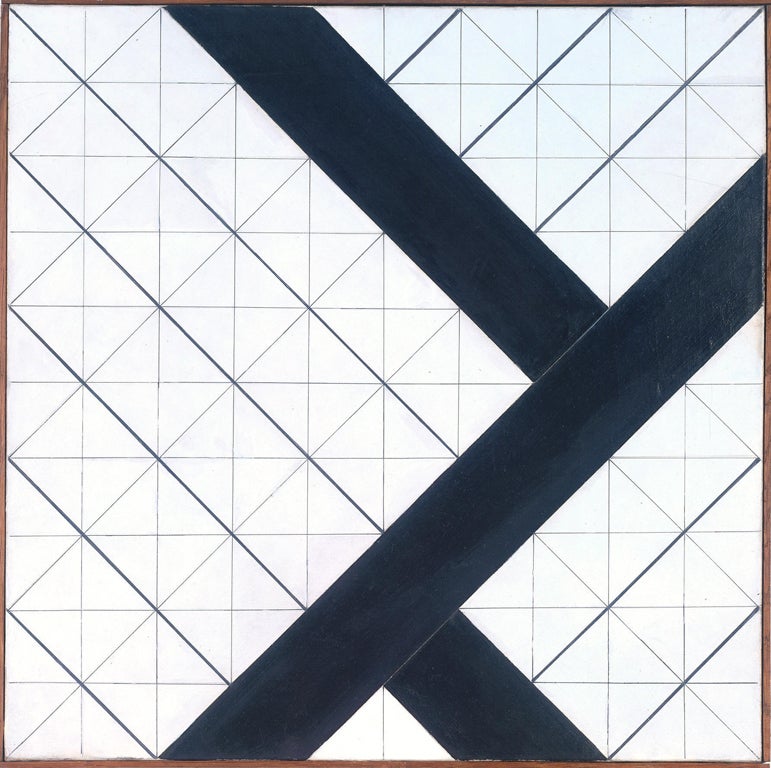

In displaying its permanent collection, therefore, the gallery has perforce tried to make up in thematic interest what it lacks in terms of masterpieces. Its new West Wing showing is called Structure and Clarity and takes as its theme the abstract work of the interwar years when a number of artist took off from Cubism and the revolutionary art coming out of Russia to divorce themselves from figurative art altogether in cool, geometrical compositions, or more organic or "constructive" assemblies. The broad movement was utopian in sprit. After the First World War artists wanted to achieve a serene balance that could take art away from human struggle. It was intellectual in the way that artists looked to contemporary architecture, technology and materials to propel its relevance. And it was apart from the world in its abstraction and its search for absolutes.

Over a dozen rooms, as it is here, it makes for interest but not exhilaration. The first room starts with two large-scale masterpieces: Matisse's Snail collage from 1953 and Bridget Riley's Deny II from 1967. The Snail, from Matisse's late experiments with cut-outs, is just a glory of colour, shape and space, each playing off each other to give energy and rhythm to the whole. Riley's work is more subdued but no less vibrant, a study of ovals in different shades of grey set against a cool grey background. It's a play on perspective. As you move around it, the picture seems to grow and bulge as if it had life. It's also a study of tone and the way the lighter contrasts seem more emphatic than the darker more obvious ones.

But then colour and rhythm seem to simply disappear from the display. Colour is subdued except where it is disciplined in the works of the De Stijl artists. Rhythm is ignored in static composition until one comes to a room near the end which, quite perversely, shows Cubism in its heyday in a handful of brilliant Braques and a major Picasso, Seated Nude (1909-10).

The openness of the display in a way plays against the pieces' virtues. Set against great white walls even the works of Ben Nicholson (and there is wonderful miniature relief from 1937) seem less involving than should be the case with a movement that at the time seemed so refreshing. Tate's attempts to bolster its thesis of measured abstraction with photographs seem a stretch too far. Photography might make abstract patterns through detail or magnification but, until the advent of digital, by its nature it presents itself as a real view of a real object, however manipulated.

There are some fine works here – particularly among the smaller sculptures of Brancusi, Lipchitz and Hepworth – and the Tate has a fair smattering of the artists of De Stijl and Bauhaus. It's good to see Brazilian and Latin American artists given their due and among some of the contemporary artists on show, I was particularly taken with the works of Saloua Raouda Choucair from Lebanon, now in her nineties, with their play on the curves and lines of Islamic architecture. Overall, however, the West Wing exhibition lacks the vibrancy and the sheer fun of the Energy and Process galleries on the same floor.

Perhaps it is the art itself. Or maybe it's the paucity of the Tate's holdings. But, prone although modern art was to schools and movements, I wonder whether coolly observed thematic display is the right way to present art quite so full of radical departures and broken boundaries as that of the 20th century.

'Structure and Clarity', Tate Modern 5th Floor, London SE1 (020 7887 8888)

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies