The eternal adventure: The amazing tale of the Arabian Nights

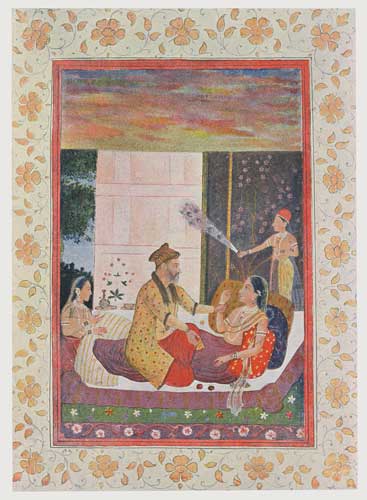

In the caliph's palace, a girl is frying multi-coloured fish when a woman with a wand bursts through the wall and demands to know of the fish if they are true to their covenant. A young man mounts a flying horse. The horse strikes out one of his eyes with a lash of his tail and lands him on a building where the man will encounter ten more one-eyed men. The Caliph Harun al-Rashid, venturing out of his palace, goes to the Tigris from where he watches a barge sail by on which a young man sits enthroned, claiming to be Harun al-Rashid... It was the wildness of the plotting and the freedom from classical constraints that appealed to the earliest Western readers of The Arabian Nights. "Read Sinbad and you will be sick of Aeneas", as the 18th-century novelist Horace Walpole declared.

The Arabian Nights, also known as The Thousand and One Nights, was made famous in the West by its first translator, the French antiquarian, Antoine Galland. The earnest purpose of his translation, published in the years 1704-1717, was to instruct his readers in the manners and customs of the Orient and use the tales to provide improving lessons in morality. Since ladies at the court of Versailles were his target readership and since the Arabic he was translating seemed to him somewhat barbarous, he took pains to render it into polished and courtly French.

The publication was an instant success, and his French was rapidly translated into English, German and most European languages. In the first instance, it was courtiers and the intelligentsia who read the book. The adaptation of a bowdlerised selection of the stories for children happened later, most notably in 1791 in The Oriental Moralist; or, the Beauties of the Arabian Nights Entertainments, by a hack pretending to be "the Rev'd Mr Cooper".

Galland had first published a translation of "Sinbad" and this had been well received. Someone misled him into believing that the "Sinbad" was part of a larger collection known as The Thousand and One Nights. More by luck than judgement, he went on to translate the oldest substantially surviving Arabic version of the Nights. This probably dates from the 15th century, but it is clear that there were earlier, less elaborate versions of the story collection. There is also at least one Turkish manuscript that is older than the Arabic one Galland translated. Though the stories of the Nights as we have them are thoroughly Arabised and Islamicised, many seem to derive from much earlier Indian and Persian tales.

In the Nights, King Shahriyar, having been sexually betrayed by his wife, kills her and resolves to avoid any future betrayal by sleeping night after night with a virgin and having her killed in the morning. The slaughter went on until Shahrazad, his vizier's daughter, volunteers to be the next to be led to Shahriyar's bed. She takes her sister, Dunyazad, with her. That night, at the post-coital moment, Dunyazad (who has presumably been lurking somewhere in the shadows of the bedroom), prompted by her sister, asks for a story.

Shahrazad starts a story, but does not finish it. Shahriyar, keen to hear the end, spares her until the next night. On following nights, Shahrazad tells story after story, talking for her life and always careful to leave a story unfinished before dawn. So the "nights" are story-breaks and there are not 1001 stories in the Nights.

Besides translating the manuscript he had found, Galland added stories which, he claimed, he had heard from a Syrian visiting Paris. These "orphan stories" are ones for which no original Arabic text survives, and they are some of the most famous, including "Aladdin" and "Ali Baba". Though some have suspected that Galland made these stories up, a Turkish original of "Ali Baba" has been identified.

In the early 19th century, a series of printed editions in Arabic were published in Cairo, Breslau and Calcutta. The most compendious is known as "Calcutta II", or the MacNaghten edition. Like the Cairo and Breslau editions, Calcutta II contains far more stories than in the Galland manuscript. Because of the way some stories lead into other stories, and stories frame others, which contain yet others, it is difficult to say exactly how many stories are in Calcutta II, but over 640.

In the 18th century, English readers made do with what is known as the Grub Street translation of Galland's French. It was the Grub Street version that inspired and delighted Addison, Walpole, Wordsworth, Coleridge and many others. Then, in the 19th century, English translations were made from the printed Arabic editions. The history of those translations is one of pedantry, pretension and plagiarism.

In 1838-41 Edward William Lane published a translation of some of the Cairo version, but since he was pious and prudish, he cut out sexual scenes and omitted a lot of stories as unfit for gentlefolk. Piety also led him to model his prose on that of the Authorised Version of the Bible, but he succeeded only in reproducing the archaism of his model without matching its eloquence. Also, since he earnestly intended his translation to serve as a guide to the manners and customs of the contemporary Egyptians, his text served as a pretext for hundreds of pages of ethnographic notes.

In 1882-4 John Payne published a much more literary translation of Calcutta II in which the sexual episodes were kept in, but played down. Payne was a self-taught polyglot and published translations from Latin, French and Portuguese. He did his translation of the Nights riding around London on the top deck of a horse-drawn omnibus.

Unfortunately, it is abominably affected and almost unreadable. When in 1885-8 that bold traveller and scoundrel, Sir Richard Burton, produced his version of the Nights, he plagiarised Lane and Payne. His weird vocabulary makes him even more unreadable. Burton also exaggerated the eroticism and violence and added a mass of unnecessary footnotes, many dealing with race or sex or both together. Lane's translation did not sell well. Burton's and Payne's editions were for private subscribers only. In the 19th century, most English readers stuck with the Grub Street Nights.

In 1899-1904 Joseph Charles Mardrus, egged on by his friend and patron the poet, Stéphane Mallarmé, produced what purported to be a new French translation of an Arabic manuscript. His translation was really a fraud. Where he was translating stories in the Nights, his renderings were deformed by obvious errors and eccentric translation strategies.

But he brought in stories from other collections and cultures and seems to have made up stories himself. Although his "translation" has no scholarly merit, it has some literary value and his version inspired Yeats, Proust, Gide and James Elroy Flecker, as well as the Ballets Russes version of Schéhérazade.

Previous English translations have dated badly, and, insofar as British people know its stories, their knowledge mostly comes from pantomime and film. "Aladdin" was first staged in 1811. Versions of "Ali Baba" and "Sinbad" followed. Although these were strictly speaking classified as "Oriental spectacles", burlesque and pantomime versions evolved later in the 19th century. In turn, the earliest film versions of the Nights, including Thomas Edison's Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves (1902) and Ferdinand Zecca's 'Alâ al-Dîn (1906)), were modelled on pantomimes.

The Nights has inspired some fine films, notably the Douglas Fairbanks silent version of The Thief of Baghdad (1924), Lotte Reiniger's silhouette animation, The Adventures of Prince Ahmed (1926), and Alexander Korda's production of The Thief of Baghdad (1940), on which Michael Powell worked. But Pasolini's Il fiore della Mille e una notte (1974) is the most faithful and intelligent adaptation, while the Disney Aladdin (1992), with Robin Williams as the wisecracking genie, is perhaps the most enjoyable.

Pasolini's version apart, these films were aimed at children and a small selection of Nights stories suitable for children survive in the popular consciousness. The Arabian Nights, Tales of 1001 Nights is freshly translated from Calcutta II by Malcolm Lyons (together with translations from the French of some of the orphan stories by Ursula Lyons) and published by Penguin Classics next week. Its aim is to reinstate the work as literature, to present it once again to an adult readership, and to make it once more a pleasure to read these marvellous stories.

Robert Irwin has edited and introduced 'The Arabian Nights' (Penguin Classics), and wrote 'The Arabian Nights: a companion'. The three-volume boxed set is available (price £112.50) from 0870 079 8897

After the 'Nights'

Salman Rushdie

'Haroun and the sea of stories'

The tangled webs of yarn which ultimately come from the 'Nights' have inspired Rushdie's fiction from 'Midnight's Children' all the way to 'The Enchantress of Florence', published this year. But the book in which he bows most deeply to the ancient sources is his 1990 children's tale, 'Haroun and the Sea of Stories'. This fable of the magic of fiction, as a son and his father seek to recapture the storyteller's art, also owes much to a modern classic himself influenced by versions of the 'Nights': Italo Calvino.

Edgar Allan Poe

'The Thousand and Second Night'

One of the first European writers to like the 'Nights' so much that he re-wrote the ending was Edgar Allan Poe, whose contribution in 1845 offered the events of one more night, apparently discovered by the author in a forgotten manuscript of the original book. In it, Shahrazad is too clever for her own good and is finally killed by Shahriyar. More recently, feminist critics have suggested that this amounted to an act of male vengeance upon women's better talent at storytelling.

AS Byatt

'The Djinn in the Nightingale's Eye'

In her collection of essays, 'On Histories and Stories', published in 2000, Byatt credited many sources, but named the Arabian Nights as the greatest of them all; it has sex, death, treachery, vengeance, wit, surprise and a happy ending. Her 1994 collection, 'The Djinn in the NIghtingale's Eye', was heavily influenced by its themes. 'Once upon a time,' begins its title story, 'when men and women hurtled through the air on metal wings, when they wore webbed feet and walked on the bottom of the sea..."

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies