Japan wants more women in construction. Pink toilets may not be helping

The industry is scrambling to deal with a labour shortage, but some say a tone-deaf government recruiting effort can’t overcome serious workplace issues

Getting hired seemed like the tough part.

Then Maho Nishioka showed up for her new job at a Japanese construction site. The workers she supervised refused to talk to her and ignored her instructions. Once, an angry client stopped her from inspecting a concrete bridge, disregarding the fact that she was the only engineer on site qualified for the job.

“He yelled at me and asked why a woman was doing the work,” Nishioka says. “I was mortified.”

Even in a country where female workers are chronically underemployed and underpaid, the construction industry has long stood out as among the unfriendliest to women. But two decades after Nishioka started that first job, a declining birthrate and Japan’s reluctance to open up to immigrants have left the construction industry – and the economy as a whole – with its deepest labour shortage in years.

Both the industry and the government see women as a possible solution. Through a public push and a marketing campaign, together they are trying to double the number of women in construction, perhaps the ultimate challenge in the country’s broader effort to involve more women in the economy.

So far the government has fallen short. Female participation in the workforce has improved only slightly. Structural issues such as long hours and relatively low wages remain major barriers.

Then there’s the government’s effort itself, which many women in the industry describe as ham-handed at best.

As part of the campaign, Japan created a pastel-coloured website in an effort to get young women interested in various types of positions in the industry. To promote female welders, for example, the site links to a cartoon that shows a woman wearing a pink, heart-patterned uniform and holding a pink, heart-shaped welding mask.

The industry is also providing female workers with portable toilets and dressing rooms – but to the frustration of many, the toilets are sometimes pink and adorned with floral patterns.

“I always think it’s clearly an idea thought up by men,” says Nishioka, 46, who now runs the diversity promotion office in the human resources department of the Shimizu Corp, one of Japan’s biggest construction companies. “I think the government should simply pursue things that would make it easier for both women and men to work.”

Hiroki Watanabe, one of the officials at the Japan construction ministry who is in charge of increasing female participation in the industry, said the overall direction of Japan’s public outreach had not “missed the mark”. Its other efforts include awarding public-works projects to selected companies that employ women, hiring consultants to hold seminars for construction executives and taking surveys of female workers.

“We will continue to do more to improve working conditions for workers and make it easier for women to enter the industry,” he said.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has sought to bolster women in the workplace through an effort called “Womenomics”, which encourages companies to promote diversity and promote female managers.

More women than ever are joining Japan’s workforce, which now has a higher female labour-force participation rate than the United States. In Japan, more than three-quarters of working-age women are in the workforce. But construction industry efforts show how difficult it will be to integrate women more broadly into the economy.

Four years into the push to double the number of female construction engineers and skilled labourers to 200,000 by 2019, the total number of women in the industry has risen by less than one-seventh. They make up only about 3 per cent of the industry’s workforce.

Attitudes remain difficult to change.

“Japan’s construction industry still rejects the idea of women actually working on the ground,” says Junko Komorita, chief executive of Zm’ken, a small contractor in south-west Japan.

“There are still plenty of men who don’t want to take orders from women,” Komorita says. Recently, one of her female employees was mocked by workers she supervised as being “hysterical” when she demanded that a certain project be completed in time.

Wages also remain a problem. Despite the labour shortage, construction workers earn on average 25 per cent less than their peers in other industries. And women in construction earn 30 per cent less on average than their male counterparts, according to a 2016 government report.

“With these wages, you can earn the same or even a bit more money at supermarkets or factories,” says Hirotake Kanisawa, a professor in the department of architecture at Shibaura Institute of Technology, “and compared to those kinds of jobs, construction is much harder.”

Most construction labourers are hired by smaller firms that are at the bottom rung of projects, where employers sometimes steal wages to cover their other costs, Kanisawa says.

But one of the biggest challenges remains the hours the job requires. Work is irregular and often involves weekends.

“You can make the work seem glamorous, but many women end up quitting when they see it for what it is,” says Natsuko Fukuyoshi, a 32-year-old plasterer in Tokyo. The hours and the physical nature of the job make it tough to keep both men and women, she says, noting that many young recruits in her company quit during their four-year apprenticeship.

Fukuyoshi began working in construction after finishing high school. She leaves her two young children at 5.30am and heads to a different project site every day. She rarely knows in advance how late she will need to stay at work.

Larger companies like Shimizu provide subsidised childcare, shorter work hours and parental leave. Another general contractor, the Takenaka Corp, built a children’s waiting room next to one of its big construction sites.

“Our staff bring their children here on Saturdays when they have to come in to work,” says Miku Shimoda, a construction manager for Takenaka. “Some of the male workers have begun using it, too.”

Shimoda, 27, is a member of her company’s Kensetsu Komachi initiative, an industry term translating to “construction belles”. The initiative, which was conceived by an industry group, encourages small teams of female engineers and employees at individual construction sites to push for improved working conditions for women there.

But even after such improvements, motherhood can often sideline a woman’s career. Rising to senior supervisory roles at big projects often requires long hours and domestic transfers.

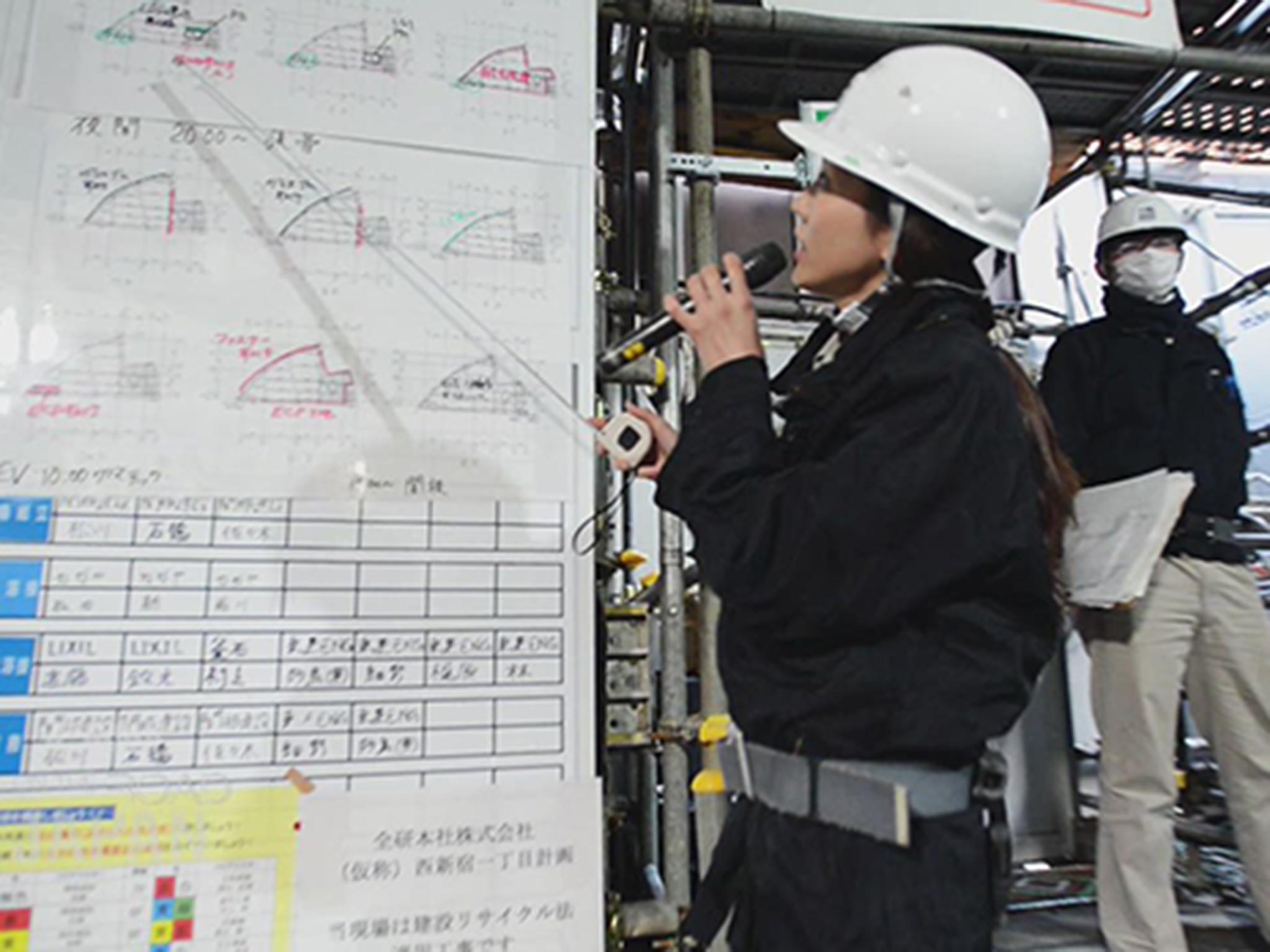

Yuho Nakamura, a 25-year-old structural work supervisor for Shimizu, sometimes spends weeks working until midnight during busy months. She and her fiancé, who works at another construction company, spend at least one day of their weekend at their sites.

“There’s definitely this image of construction being a macho industry,” says Nakamura, who was hired by Shimizu three years ago, “but I heard that more women were joining, and I always dreamed to be one of them.”

She said she hoped someday to oversee an entire building site as a lead supervisor. For now, of the roughly 300 workers at the busy construction site in Tokyo where she works, she is frequently the only woman.

Nishioka, the Shimizu diversity promotion executive, once had a similar hope.

“I used to dream about going back to the field,” she says. “But now, I leave it up to the younger generation.”

© New York Times

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies