Going viral: How business caught the bug

Funny online clips might have kicked off the craze for viral videos but this technology trend is having a huge impact on how companies across the world succeed. Tim Walker reports

If all you knew of viral culture was a brief clip of an overweight child pretending to be a Jedi knight in his garage, or another of a pair of men in lab coats recreating the Bellagio Fountain in Las Vegas with Diet Coke and Mentos, then you could be forgiven for thinking that going viral was a matter of sheer chance – that nobody could predict what would flourish on the internet, and what would be choked off at the root.

But as Adam L Penenberg explains in his new book Viral Loop, there is a formula for virality that doesn't just apply to YouTube celebrities like "Star Wars Kid" or to Fritz Grobe and Stephen Voltz (the men behind the Diet Coke and Mentos clip). It also provides the business model for many of today's most celebrated young companies, including eBay, Facebook and YouTube itself.

In one crucial way, an online "viral" is unlike the contagious diseases from which it takes its name, and which are spread unintentionally by their victims. "A viral loop is like a virtuous circle," explains Penenberg. "It's what happens when you have a product or service that your users are spreading because they want to, or because it's built into the product."

Penenberg has a list of principles that apply to most successful viral loop businesses. The service or product they provide is generally free and simple to use. It also either has virality built into it, or becomes better the more users it has, thus encouraging its users to promote it to others. After all, what's the point of creating a Facebook account if none of your friends do the same? Why be on eBay if there's nobody to buy from or sell to?

Viral Loop, says its author, is the first lengthy examination of the viral phenomenon in its relatively short history. "No one else has looked expansively at the impact of virality, yet the internet is the biggest viral plane we've ever had. Anything that touches it has the potential to spread more quickly and efficiently than ever in history. Businesses can grow from nothing to billion-dollar enterprises within a few years."

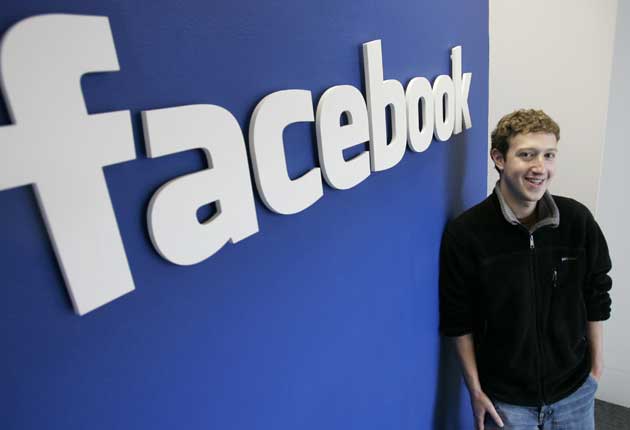

Some of the most successful viral loop companies have come about almost by accident. Mark Zuckerberg, the young coder who created Facebook, planned simply to create an open version of the official Harvard college facebook. Six years later, he's the CEO of a $6.5bn business. Programmer Pierre Omidyar created eBay in 1995 as an add-on to a personal hobby site. The first thing he sold was a broken laser pointer. When the company went public three years later, he became an instant billionaire.

Other viral loops have come about more deliberately. When Hotmail – the first popular webmail site – launched, its creators decided to affix a short message to the bottom of every email sent: "Get your free email at Hotmail." This alerted each mail's recipient to the existence of the wonderful new technology, and they had a million users within six months. The people behind Paypal, the most popular closed payment system on the web, offered every registered user $10 simply for signing up to the service, guessing correctly that it was a cheaper and more effective path to swift growth than a traditional marketing campaign.

Paypal also emerged in 1999, at a point when eBay's army of users was desperate for a simpler way to do business with one another. Despite eBay's attempts to obstruct it, Paypal was such a success because it was able, as Penenberg puts it, to "stack" on top of an existing viral loop. The same is true for YouTube, which first became popular as a way for MySpace users to share video content. Nowadays YouTube's user numbers far outstrip those of MySpace.

Yet while sales commissions give Paypal and eBay straightforward revenue streams, it seems harder to understand how free services such as Facebook and Twitter make real money to match their theoretical valuations. "Twitter could layer in revenue schemes and become very profitable tomorrow," says Penenberg. "All it'd have to do is charge businesses a subscription to be on the site. But it's more intent on growing. Users have value. If it had three million users instead of 300 million, Facebook would be worth a lot less."

Viral loops may sound like an ultramodern idea, but as Penenberg explains in his book, the principle has been around for years. The jokes you used to hear in the playground after a news event were the equivalent of viral videos, and were initially disseminated by city traders, who had the most advanced communications technology at their disposal. Tupperware parties are an early, highly successful, business example of the viral loop, as are Ponzi schemes. "Bernie Madoff is the ultimate viral schemer," posits Penenberg.

Politicians, too, have benefited from the viral loop. Barack Obama, who hired one of Facebook's founders to run his community of online supporters, persuaded countless volunteers from that community to promote his candidacy and solicit donations on his behalf, raising a record-shattering budget for his presidential campaign.

Penenberg began his career as an investigative journalist. For some years now he has been writing about the tech industry for Fast Company magazine, among others. "I have written critical pieces about a few major companies," he admits. "Amazon will never invite me to lunch, and nor will Apple. I have a contentious relationship with Google, and Microsoft has probably banned me from the campus ... But then nobody's popular in the Silicon Valley media. It's a cesspool. It makes Wall Street seem touchy-feely."

He did, nonetheless, persuade many of the major players in the Viral Loop story to assent to exclusive interviews, including Zuckerberg. "I told him that all I wanted to talk about was the early years of Facebook and its viral growth paradigm, and his eyes lit up."

Naturally, the book comes with its own viral marketing campaign that will, if all goes to plan, prove the efficacy of the viral loop. There's a Viral Loop Facebook application that calculates each user's financial value as a member of the Facebook community; it has already attracted around 10,000 users. The Viral Loop iPhone app lets users buy and sell (with virtual currency) predictions on everything from the fluctuations of the Dow Jones index to the timing of the next Twitter outage. "I felt when I wrote the book," he explains, "that if I didn't try to create my own viral business scheme then it would only be worth the words on the page. But if I could show how it works that would be worth a lot more."

'Viral Loop' by Adam L Penenberg is published by Hodder tomorrow, £12.99. Read more: an extract from the book, plus an interview with James Hong, co-founder of Hot or Not, one of the first viral phenomenons, is at independent.co.uk/viral-loop

Digital visionaries: The leading web theorists

Chris Anderson

The US editor of Wired magazine is also the author of two bestselling books about business and the web. His first, 2006's The Long Tail , describes the opportunities the internet presents to retailers offering niche products. Anderson suggests that in future, rather than markets being dominated by a few mass-manufactured items, the internet will allow people to sell of a large variety of different products in small quantities. A Harvard Business School study disputed Anderson's theory, suggesting that the internet merely amplified the success of blockbuster products. This year Anderson released Free , examining pricing models that allow users to access products and services for free, while generating revenue for their producers in innovative new ways. Like the Long Tail theory, its conclusions have been both praised and criticised.

Clay Shirky

An expert on the social effects of new media, Clay Shirky teaches a course on this topic at New York University. His 2008 book Here Comes Everybody is, he says, about "what happens when people are given the tools to do things together, without needing traditional organizational structures." The internet will change communities, writes Shirky, but there's no way of quantifying whether this change will be for good or ill. And in any case, "Communications tools don't get socially interesting until they get technologically boring... It's when a technology becomes normal, then ubiquitous, and finally so pervasive as to be invisible, that the really profound changes happen."

Bill Wasik

Journalist Bill Wasik is not so much an expert on technology as a viral pioneer, the 'Patient X' of a number of viral sensations that he deliberately concocted, then recorded in his recent book, And Then There's This . Wasik's most famous creation was "flash mobbing", whereby a large group of people, drawn by a virally disseminated email, would descend on a single location at an appointed time for no discernible reason, baffling the police and latterly providing advertisers with an effective new marketing method. The book is an irreverent analysis of the way trends or, as he calls them, "nanostories", flourish and die in a culture where everyone can indeed be famous – but rarely for as long as 15 minutes.

Charles Leadbeater

Like Shirky or Jeff Howe (author of Crowdsourcing ) Charles Leadbeater is an expert analyst and exponent of the power of social media. A former associate editor of The Independent who has advised the Government about the internet, Leadbeater's 2008 book We-Think celebrates the web's power to transform society for the better, enlivening democracy and generating "mass innovation, not mass production." The book itself began as a collaborative endeavour: a first draft appeared online in 2006 and readers were encouraged to provide comment and criticism, which Leadbeater used to complete the final, published version.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies