The winter of our disconnect

Christmas is the time when we put aside our online identities and rediscover the rich complexity of real-life encounters. Help! says playwright Lucinda Coxon

I won't be sending many Christmas cards this year. I was never very good at it, regularly only getting halfway through the (mostly out of date) address book before the rollerball ran out of ink and the stamps got stuck together with spilt seasonal spirit. Trailblazing Henry Cole conceived of the Christmas card in 1843, as he was desperate for something pre-printed to spare him the manual labour of his Yuletide correspondence. Now, simply signing our names and addressing envelopes feels like too much.

So, this year, I'm taking Henry Cole's idea and running with it. It's the logical next step: broadcasting my goodwill via Facebook. On Christmas Eve, I'll be crafting some very-nearly-witty status report, which aspires to the perfect blend of irony and schmaltz. And I guess it will end up being read not just by my FB "friends" (mostly work contacts who wouldn't expect a card in any case), but also "friends of friends" and maybe even their "friends" too. And since the world is now allegedly down to just four degrees of separation, I assume it won't be long before Kevin Bacon himself briefly sets aside his glass of cheer to chortle over my Merry Whatever.

In other words, I'm completely absolving decades of Christmas card guilt by committing to some essentially meaningless contact with an enormous number of people, many of whom I don't know, don't much care about and might not like if I met them. And what's strange is that I feel pretty okay about that. Is that so bad? Or so unusual? After all, Christmas is traditionally a time for playing fast and loose with the truth. They start us young, with the whole "wish-list up the chimney" routine. So a little moral fudge with my proliferating virtual pals is surely, just like Santa Claus, a harmless escapist buffer against the gruelling reality of the season.

No matter how much we love it – and I do – Christmas is a time of unspeakable stress, producing dramatic spikes in depression and divorce before the flames on the pudding have fizzled out. Never mind the sense of exclusion for those who are alone or flat broke at a time of year that markets itself with endless images of families enjoying loved-up overabundance. That overabundance itself is a killer, too.

It seems that, while the combined forces of overspending, overeating and sanctified binge drinking are more than enough to cause expectations to crash and burn, the excess that pushes most people over the edge is this: prolonged and unmediated exposure to their nearest and dearest.

And, worryingly, unmediated exposure to other people in general, never mind our relatives, seems to be becoming increasingly difficult for us to bear. In a world where a huge amount of our time is spent negotiating reality through screens – TV, computer, phone, tablet – we are starting to struggle without a shield in place.

The 2011 World Unplugged Experiment asked 1000 students in 10 countries to turn off their media for a day. They were bereft without the aural insulation of their MP3 players, foxed by having to be a coherent version of themselves, rather than operating as multiple identities, variously geared toward email, text or social networking sites.

They struggled socially to be spontaneous and flexible, having grown accustomed to being able to consider and control.

And it's not just the LMFAO generation in trouble with this. Technology has made screenagers of us all. We've all got used to the buzz of unilateral agency; acting on impulse, but from a safe distance. A few clicks of the mouse saves us a trip to the reference library – Google knows what we want, based on what we wanted before, limiting our horizons, but enforcing our sense of mastery.

We buy books, rail tickets, free-range turkeys online, without the bother of crowds and queues. It's so pleasingly different from messy real-life encounters; encounters that might have broadened our sense of the world and ourselves; developed our social tolerance.

My latest play, Herding Cats, is about the perils of pretending to be people we aren't and the extraordinary opportunities that modern living affords us to do so, in a world free of accountability or contradiction. All seems unnaturally normal in this world, where the characters are sometimes voyeurs, sometimes performers; where "friends" are a kind of audience. But the home truths of the festive season change everything.

As communications technology shrinks the globe into a glittery bauble, it offers the seductive lure of the Christmas list; of desire being interchangeable with reality.

It makes us feel bigger than we are.

A family Christmas, no matter how congenial, will generally have the opposite effect. It is full of flesh and blood immediacy; packed with reminders that some dynamics never change, no matter how many Kindles pre-loaded with Personal Development For Dummies are lovingly gift-wrapped and left under the tree.

Like all real encounters, it is unstable, contradictory, rich and sometimes overwrought; sometimes feeling like too much to deal with.

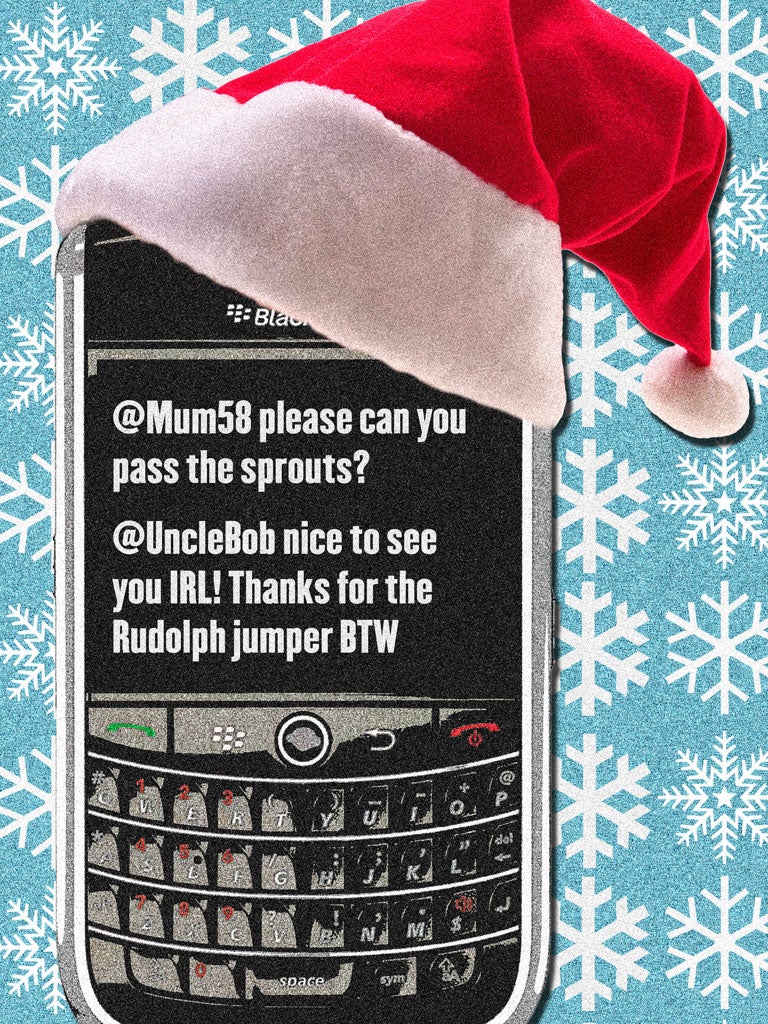

So how early on Christmas Day will you reach for the oxygen mask of your virtual existence? A sneaky tweet? A round of Angry Birds? A Skype call to a sibling who is comfortingly far away?

But before we berate ourselves too cruelly, it's worth remembering that Henry Cole's first Christmas card was controversial in its day, not because it ushered in a new degree of inauthenticity with its preprinted message. Rather, because of the scene it depicted: a family feasting on a slap-up lunch, with a loving mother encouraging her small child to knock back a glass of red wine.

It seems we've needed something to take the edge off the raw truth of the season for longer than we'd like to think. A new age simply furnishes new solutions. So, sloe gin or Crackberry? Choose your poison. And cheers.

Lucinda Coxon's play Herding Cats is at London's Hampstead Theatre until 7 January. Booking: 020 7722 9301 / hampsteadtheatre.com

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies