Health scares: A dose of common sense

The numbers may be alarming – but what's the real risk of catching swine flu or developing cancer? Jane Feinmann calculates the truth behind the data

If nothing else, swine flu has made us aware of the horrible risks of trying to understand medical statistics. Knowing whether this pandemic ends up "threatening humanity", or whether it's a media panic that's all nonsense and hype, is way beyond most of us. That's because, with a few exceptions, we're all illiterate when it comes to statistics – and it's a risky failing.

The inability to put a statistic in context puts people at the mercy of media-hungry doctors, headline-grabbing journalists and politicians and big pharmaceutical companies all keen to manipulate statistics for their own purposes – and that's dangerous when statistical findings can be vital to getting the best treatment when we're ill. It's not easy to spot these tricks. But here are the key ways to demystify health statistics and learn how to make them work to improve your health and wellbeing instead of frightening you to death.

The Pill doubles the risk of DVT

In October 1995, millions of British women woke up to the news that the latest (and apparently safest) oral contraceptive was a dangerous time bomb – carrying a 100 per cent increased risk of developing life-threatening deep vein thrombosis (DVT). The warning was based on new research and backed by the Committee on Safety of Medicines – and, not surprisingly, large numbers of women stopped taking the tablets without considering the consequences, resulting in a sharp increase in the following year's abortion figures. Even at the time, there were warnings that the 100 per cent risk was not as frightening as it appeared to be. The full truth emerged three years later in a World Health Organisation review of the evidence. True enough, it was possible to describe the relative risk of developing blood clots in legs and lungs in the third generation Pill compared to the second generation Pill as 100 per cent. But the absolute increase was minuscule – from 1 in 7,000 women having a blood clot to 2 in 7,000.

"Had the public been informed of these statistics, this panic would never have occurred," says Gerd Gigerenzer, of the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin.

Lesson: always read the small print

Studies that report only the relative risk of taking a drug or having a particular treatment can provide useful information – but only as part of a bigger picture. On its own, this type of research finding can be "non-transparent" – ie, deliberately blurring the facts to sex up dull findings or present the findings in a more or less favourable light, often to make a political or health-related point. So look at the small print and find out the absolute risk of any intervention. That's what counts.

One drink a day causes breast cancer

We're repeatedly told that the double blind, placebo controlled, randomised clinical trial is the gold standard research method. Yet we're also bombarded with so-called scientific findings derived from studies that have nothing in common with this model of excellence. In February, for instance, the media reported the apparently authoritative finding that drinking one small glass of wine a day increases a woman's risk of developing breast and other cancer by six per cent. The research, part of the Oxford University Million Women Study, claimed to have shown that 7,000 cases of cancer in British women were directly caused by the consumption of a single daily alcoholic drink – and that there is no threshold at which alcohol consumption is safe.

So far, there's no hard evidence that women are becoming anxious with each sip of chilled chardonnay. But if they are, it's probably premature. The finding seems impressive because the study involves so many women.

But the results were entirely dependent on the million participants self-reporting their drinking habits – "the weakest kind of epidemiological endeavour and certainly nothing close to the gold standard of a randomised controlled trial," according to Patrick Basham and John Luik, health policy experts at the Democracy Institute.

"None of these reports was checked and the authors can make no claim about how reliable they are. No one knows how much or how little these women really drank, since no one bothered to measure it."

Dr Mark Little, reader in statistics at Imperial College London, agrees. "There is a great deal of evidence that people don't accurately recall or report how much they eat or drink and that there are numerous examples of substantial errors in research that relies on this kind of self-reporting," he says.

Lesson: not all research is equal

Be aware that epidemiological studies should be only one piece in a larger jigsaw. There also needs to be further research to assess the importance of this finding.

More men survive prostate cancer in the USA than in Britain

In 2007, the former mayor of New York Rudy Giuliani claimed that as a prostate cancer sufferer, he had an 82 per cent chance of surviving in the US compared with a 44 per cent chance in the "socialised medicine" of the NHS.

"In fact, the length of time people live with prostate cancer in both countries is about the same," says Professor Michel Coleman, of the London School of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. "What has happened is that a political message exploits characteristics peculiar to prostate cancer."

Giuliani's statement is based on data from 2000 when the US had established a screening programme for prostate cancer using the PSA test – something still not universally available in the UK. "There is a very slow-growing type of prostate cancer which is both common and largely symptom-less and therefore only diagnosed with PSA testing," explains Professor Coleman. "So there is a larger pool of diagnosed prostate cancer sufferers in the US, many of whom had the slow-growing type of cancer and therefore probably died in old age of something else. That skewed the statistics."

Another factor is that survival, in the context of clinical research, has a much more specific meaning than it does in everyday language – ie, living for five years after diagnosis.

As screening in the US enabled diagnosis to occur at an earlier stage in the disease, it was natural that the US population with prostate cancer had a higher chance of "survival".

Lesson: watch out for clinical spin

Treat the word "survival" with caution. "If there is no clear comparison of like with like, the research is not worth reading," says Professor Coleman.

One in nine women will get breast cancer

"One in nine women in the UK will be diagnosed with breast cancer." It's a statistic that gets bandied around – particularly by fund-raising charitable bodies or academic departments chasing research money. The statistic is true only with the extra information that this is a life-time risk and that a large proportion of the one in nine women diagnosed with breast cancer are elderly and will die of something else, probably heart disease. "Many people assume that one in nine women get breast cancer in a single year, something that is entirely untrue," says Professor Coleman.

Lesson: beware of scaremongering by fund-raisers

If you're not being told the timescale, take the warnings with a large pinch of salt.

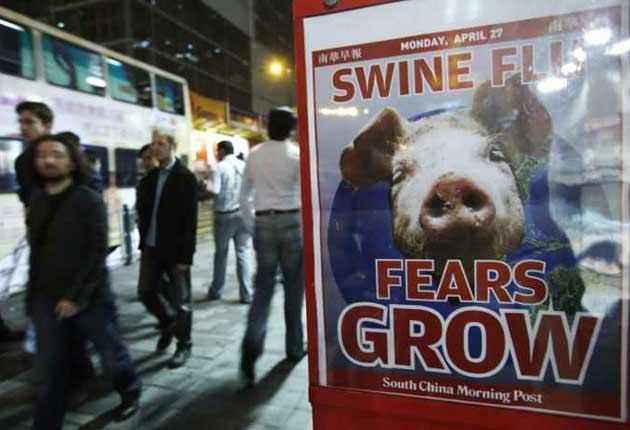

Swine flu will kill millions

Ridiculing the Department of Health for over-egging the risk of swine flu has become a favourite pastime in recent weeks. But acknowledging uncertainty and preparing for the worst case scenario is a legitimate and sensible scientific position, according to David Spiegelhalter, Winton Professor of the Public Understanding of Risk at Cambridge University.

Risk is "an odd thing", he explains. "It can't be measured – but it constantly changes as we find out more information."

The extra information that is currently not available includes knowing how infectious the virus, the proportion of cases that might die and whether it could mutate.

Lesson: be aware of how much we don't know

"It can be disastrous to believe that you have thought of everything," Professor Spiegelhalter says.

MMR causes autism

Vaccination programmes targeted at particular age groups are highly susceptible to this type of scare. The latest horror story links cervical cancer jabs for teenagers with severe side effects including paralysis, epilepsy and sight problems.

Campaigners are calling for the suspension of the immunisation campaign to protect against the sexually transmitted HPV virus that causes 70 per cent of cervical cancers. The issue threatens to be a copycat of the campaign that wrongly terrified a generation of parents into believing that the MMR vaccine caused autism.

Perhaps one problem here was that parents instinctively trusted their own experience over what the supposed facts told them: most of us know a child with autism, but few will now encounter one with measles, so that skews our view of the relative risks.

The Department of Health has issued reassurances that with 700,000 girls vaccinated last year, the risks are so far "minor or unproven" and do not outweigh the benefits of the vaccination programme.

"These reports may seem to have a scientific basis, especially to worried parents. But however convincing, these random reports of adverse consequences mean absolutely nothing," says Professor Coleman.

Lesson: don't be scared by anecdotal evidence

Every medicine or vaccine is likely to have some side effects. But bear in mind the lessons from MMR and wait for the scientific studies before making a judgment.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies