Why we worry too much about health

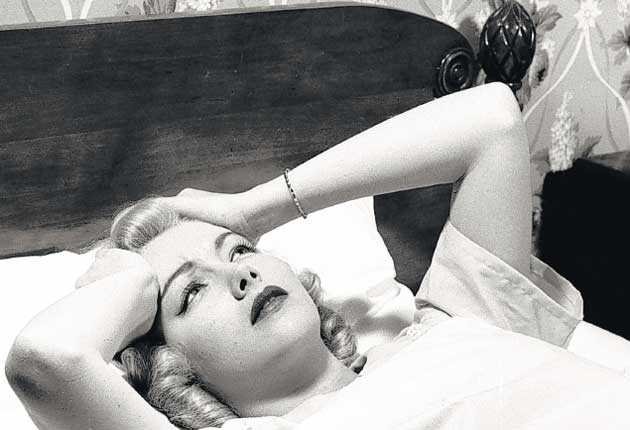

Eat your five-a-day, take exercise, avoid alcohol, sugar, stress... Worrying about our wellbeing is dominating our lives – and it's bad for us, say the authors of a new book. Rob Sharp hears why

The rise of modern medicine has provided a convenient altar at which the world's worriers may kneel: the newspaper health scare story. It might not be the same as donning a hair shirt, but surely if we fret about mobile phones/X-rays/oxygen giving us cancer, take every test and gulp the right pills, a guardian angel will reward us for our vigilance with a long and fruitful life?

Not so, say Dr Susan M Love and Alice Domar, the co-authors of Live a Little!, Breaking the Rules Won't Break Your Heath, a new guide to healthy living published in the US late last year. In the book the pair make the case that many of us are living healthier lives than we may realise.

"We wrote the book because the media is telling us what's healthy and what's not the whole time," says Love, a clinical professor of surgery at UCLA. "People take it seriously. You must have eight hours' sleep a night, have no stress, drink eight glasses of water a day, exercise the whole time. It makes you crazy. We're simply asking what was behind these rules. Who is asking them? We wanted to find out if the old wives' tales were substantiated and most of the time they weren't."

Peter Bull, a reader in personality and social psychology at the University of York, believes constant worry about health is an endorsement of doctors' proficiency. "People think things are more curable these days," he says. "In olden times many people believed if something dreadful happened it might make them a better Christian. Illnesses were accepted as a fact of life. It's the same with poverty. Contemporary society views it as soluble. Historically, society viewed it as the way things are, and should be."

So stretch out those worry lines, nervous Erics and Ericas. Health experts Love and Domar tell us how to de-stress over some of the key health areas.

Sleep

A 2008 survey by YouGov suggested that 68 per cent of Britons are not getting eight hours of sleep a night. The findings are echoed over the pond – the US National Sleep Foundation found in 2002 that three quarters of Americans had trouble sleeping. A third, the organisation claimed, were so sleepy during the day that their normal activities (household chores/working lives) were disrupted. But should it get our goat? The experts think such polls give off the wrong impression. "It looks like you need at least six hours' sleep, with seven being ideal," says Love. "But if you have a lot less for a couple of days, terrible things are not going to happen. You can catch up. It's all about the general pattern over your lifetime, not what you do day-to-day."

Research conducted in 2006 by Warwick Medical School at the University of Warwick discovered sleep deprivation is associated with an almost a two-fold increased risk of obesity for both children and adults. But Domar adds that there still needs to be a lot of work done in the field. "There's no direct causal relationship between sleep deprivation and obesity and heart disease just yet, despite some of the story headlines," she adds. "Unhealthy people tend to sleep a lot but we don't know if it's the disease making them sleep or vice versa. If you look at the data, those who sleep for seven hours a night throughout their entire lives tend to live the longest. But if you're sleeping seven hours a night and you are still feeling exhausted you should just sleep more. There's no hard and fast rule."

Stress

We manage anxiety like we'd tip-toe along a tightrope. Sway too far one way, you decline into lethargy. Lean in the opposite direction and you'll land in heart attack country. It's well publicised that worried people are courting coronaries. According to an ongoing study in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, of 735 American middle-aged or elderly men who had good cardiovascular health in 1986, those who scored highest on four different scales of anxiety were far more likely to suffer heart attacks in later life. What's the flip side? "No stress is not good either," says Love. "If you look at the studies, those whose heart rate never goes up are on a fast track to death. You need to have adrenaline rushes, so that when you do get stressed you know how to deal with it."

Domar agrees. "Stress improves your performance to a point, above which the way you handle things rapidly declines," she states. "You want highs and lows to live an interesting life."

Even so, there's no doubt avoiding the upper end of the stress spectrum is probably a good idea. "I think it's important to say that anxiety can be adaptive," says Bull. "If you're anxious you may act to improve a bad area of your life. If you ignore things in blissful ignorance you might be asking for something to go wrong."

Prevention

Experts rally against confusion between "prevention" and "early detection". The US National Cancer Institute recommends that women over 40 get mammograms every one to two years. Here in the UK, regular screening doesn't start until 50. "Mammograms don't prevent cancer, they just catch it an early stage," says Domar. "In the same way, a colonoscopy will not prevent you from getting polyps, it might just catch them before they become cancerous." That doesn't mean you can skip screenings, though. "High blood pressure, if not treated, is associated with heart attacks and stroke," Love continues. "If you detect it early you can make changes to your lifestyle that may alter it. But if you go for a mammogram that doesn't necessarily mean you're suddenly not going to get cancer. This is a common grey area." The American Cancer Society recommends that women have their first Pap smear test about three years after they become sexually active or by age 21, whichever comes first. After that, the tests should take place every two years. In short: don't exceed the recommended test regularities, as believing a high number of tests will make you healthier might breed false hope. "Don't get confused about it; it's the medication that will ultimately help you," concludes Domar.

Nutrition

The healthy diet rules should possibly be inscribed into the side of a mountain somewhere: keep your saturated fats low, avoid too much salt and sugar, maintain a balance between roughage, vegetables, fruit, proteins and carbohydrate. But be wary of following rules that are too prescriptive – five portions of fruit or vegetables a day, 2,000 calories for men and 1,500 for women, a complete abstinence from fast food. "The data really isn't there to support such stringency," says Love. "There's no evidence that antioxidants reduce cancer," she continues. "We know that if you have a Mediterranean diet high in fruit, vegetables and unsaturated fats that's going to be good for you but if you have a steak one night you're not going to drop down dead. The rules are a lot looser than you may think. If you stray, it's basically OK." The authors say three or four portions of vegetables is probably not a lot worse for you than five.

The pair point to the lack of evidence regarding the positive effect of vitamin supplements, on which we spend millions each year in an effort to ease our health anxiety. Scientific consensus dictates that most have little or no effect, apart from vitamin D in sunshine-poor environments. Those who eat a balanced diet should be OK. "It mirrors the proven effects of herbal remedies, again, which are mostly disputed [the strongest evidence seems to be in favour of echinacea and St John's wort]. I would say that the immune-boosting effects of echinacea are just as likely to be due to the placebo effect than anything else," says Domar.

Exercise

The Government's department of health recommends adults should get 30 minutes of moderate exercise, five days a week. But the most recently published annual Health Survey for England, published last December, shows that 94 per cent of men and 96 per cent of women do not achieve this. Is this, finally, a source of worry? "Some people can be naturally fit and they don't need to exercise so much," says Love. "If you're a young mum and you're carting around a toddler you probably don't need to spend so much time in the gym. It can depend a lot on your age. You're going to be a lot less agile when you're older but any kind of activity is going to be useful to your well-being. It mirrors what happens with people's blood cholesterol. If it's naturally low you probably don't need to spend so long taking care of your diet."

Still, being on first-name terms with a personal trainer won't hurt. "While Americans are told to exercise 60 minutes a day, that is not based on any control-based research," adds Domar. "But I still think that exercise is the single best thing you can do. It's good to be active the whole time. Young people tend to be fitter than they think they are. What we're doing is trying to remove the guilt if you can't achieve these lofty targets."

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies