My journey through the big C – when doctor became patient

As a GP, Youssef El-Gingihy ought to have spotted the warning signs for cancer. But like many people, he dismissed them. Here he talks about the voyage the illness took him on, the incredible advances in treatment in recent years, and the prospects for a cure

The autumn of 2015 was meant to be yet another passing season. I should have known something was badly wrong when I started finding the morning commute exhausting. I felt lethargic as I dragged myself up the stairs of the tube station. By the time I managed to clamber on the train, my armpits would be sweaty even though I had just showered. I put it down to how infernally hot the Tube can be. When I surfaced from the underground, I was knackered before I had even arrived at work. Clearly I needed to get fit!

But it wasn't just at work. At weekends, my girlfriend noticed that I was lacking in energy when we went out. I often found myself sitting down and asking her to carry on without me. Again, I put it down to the boredom of shopping. Then I noticed that my trousers were looser. I managed to dismiss this too; wishfully ascribing it to leading a better lifestyle.

As a doctor, I should have known better. If I had taken a step back, I would have realised that the above descriptions could be neatly summarised as lethargy, sweats and weight loss. If this catalogue of symptoms had appeared in any exam situation – and boy had I done enough exams – I would have told you straight off that these were serious, constitutional symptoms warranting further investigation.

Yet it never occurred that something was wrong. After all, I was in the prime of my life at the age of 35. And I was the one looking after patients, not the other way round, or so I thought. Even so, if I had gone to see my GP at this stage, my examination, blood tests and chest X-ray would have likely been normal.

The medical textbooks tend to engage in the hyperbolic. Weight loss is dramatic. Sweats are drenching. Lethargy is a state of perpetual torpor not occasional lassitude. The reality was that my symptoms were insidious and innocuous explaining how they had slipped under my medical radar.

However, when I noticed a solid neck lump whilst shaving one morning, I booked an appointment with my GP. Before I knew it, I was on the conveyor belt. I found myself at an urgent hospital appointment, where I was subjected to a camera test in order to look down my throat. “Pristine,” the ENT surgeon declared.

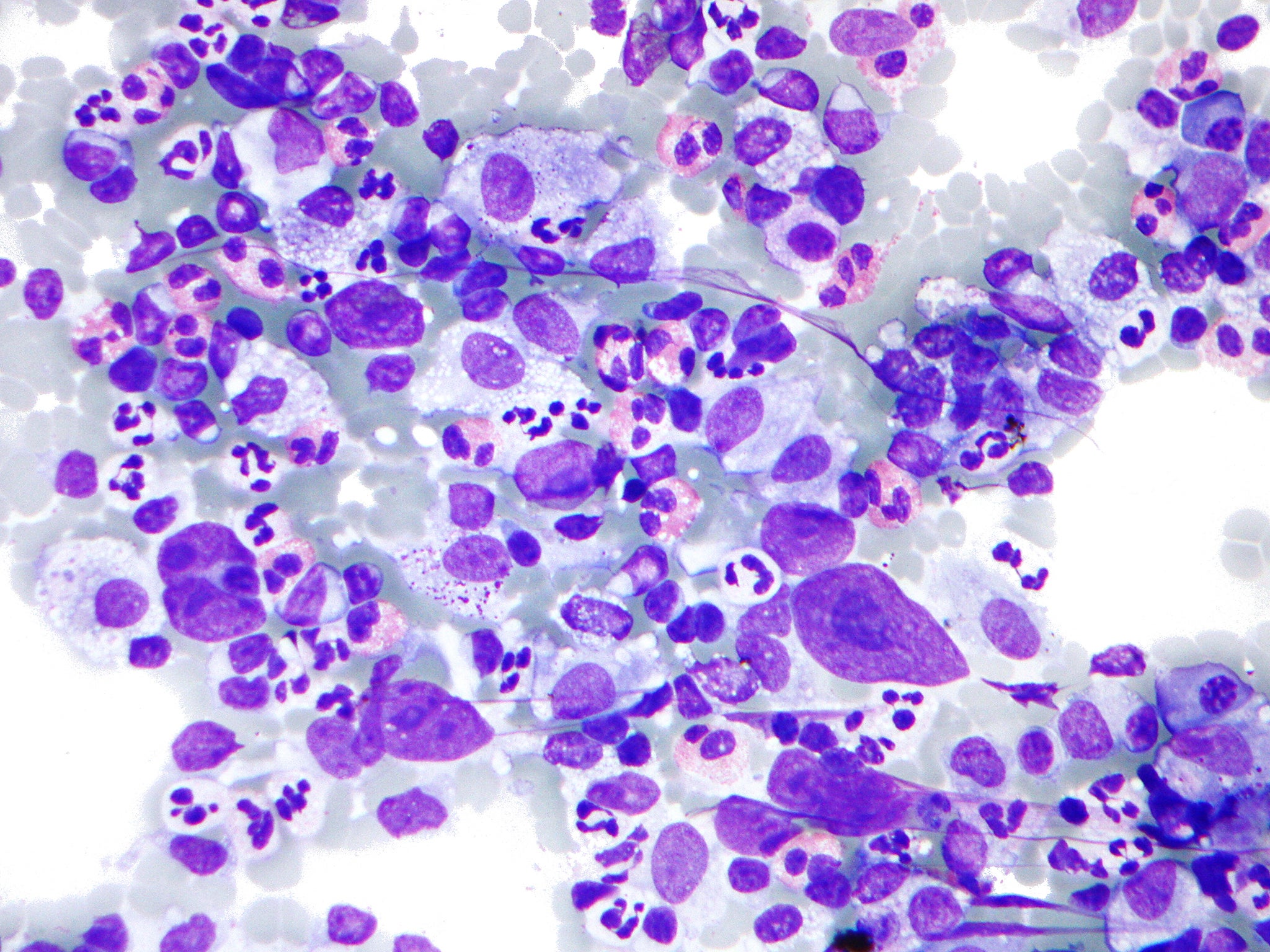

Next up was an ultrasound scan involving a large biopsy needle, which proved to be remarkably painless in the skilful hands of the consultant. The concerned reaction of the radiologist and pathologist, though, set off alarm bells. In due course, the dreaded diagnosis of the big C was imparted. I was informed that I had developed Hodgkin’s lymphoma – a blood cancer classically affecting younger patients.

In the past, I would have required an unpleasant bone marrow biopsy for diagnosis. Patients even underwent a laparotomy – open abdominal surgery – in order to stage the spread of the disease. Now all that is required is the wonder of a PET (Positron Emission Tomography) scan; not only for staging but also for confirming resolution of the disease. It works on the principle that the glucose or sugar consumption of cancer cells is greater than that of normal cells. A radio-labelled glucose tracer is injected and the PET scan images the uptake of this tracer. The cancerous lymph nodes light up brighter than other tissues. It is a surreal experience lying under a scan as it portends your future by revealing how far this silent enemy had multiplied inside me.

In the space of a traumatic fortnight, my life had been turned upside down. It was hard to imagine a silver lining. But, as one of my consultants pointed out, the good news was that treatment for Hodgkin’s lymphoma is given with curative intent. And there are not many things you can say that for in medicine. Most conditions are simply treated as long term.

Hodgkin’s has been a success story in oncology. The prognosis for early disease is now very good. In fact, overall UK survival for all cancers has doubled over the past 40 years. The treatment for Hodgkin’s has been modified over recent decades mirroring astonishing advances in cancer therapy. Toxic chemotherapy regimens have been replaced with better tolerated ones. Radiotherapy was previously given extensively at higher doses but is now targeted at much lower doses.

I was terrified at the prospect of chemotherapy. You might imagine that a medic would at least know what to expect. But I now realised the limits of my knowledge – pretty much all I knew about chemotherapy was from medical school. We simply had not been taught that much about this complex and continually evolving subject. Unless you are a cancer specialist, the chances are you will not know a great deal about it. As with every field, medicine has become super-specialist. The age of the generalist in medicine, let alone the Renaissance man, is a thing of the past.

And it’s no surprise that I was petrified – the mental image I had was of kneeling over the toilet being sick, all your hair falling out, unable to eat, feeling very ill and being admitted for intravenous antibiotics with life-threatening infections due to a wiped out immune system. Much of this comes from the ingrained representation of cancer treatment in popular culture. Some of it came from my brief dealings with the sickest cancer patients – the ones admitted to hospital – and was therefore necessarily skewed.

When I was informed that the standard chemotherapy regimen for Hodgkin’s was manageable, I was disbelieving. When my consultant advised that this was a moderate regimen, which was generally well tolerated, I almost scoffed. It felt like the kind of reassuring platitude that we doctors are very good at regurgitating. Of course, each chemotherapy regimen is different and one cannot predict how an individual will respond to a particular drug. Being young, fit and healthy, with good physiological reserve, was certainly in my favour.

After my first bout of chemotherapy, I merely felt very tired; as if I had worked a long day or been doing night shifts. I did not experience any nausea, such are the effectiveness of 21st-century anti-emetics (anti-sickness drugs). I even heartily ate a pizza that evening. My appetite was largely down to the steroids. The roids, as I called them, cause all manner of side effects. They disturb the sleep-wake cycle and cause mood swings. This means that you turn into a grumpy insomniac, who demolishes the fridge in the middle of the night.

I woke up the next day feeling as good as new. In fact, I felt so well that we decided to go on the junior doctors’ protest march and I even managed to speak in front of thousands at Parliament Square. I felt great – well if this was chemo then bring it on! I even joked, paraphrasing Muhammad Ali, that I could wrestle with an alligator and tussle with a whale. A word of warning – never, I mean NEVER, tempt fate in this way.

On the Sunday evening just before bedtime, minding the advice on dental hygiene, I swigged some strong mouthwash hoping it might ward off any potential bugs. The next day, I woke up with mucositis or inflammation of the lining of your mouth and throat. This is one of the side effects that patients rate as among the worst. The mucositis triggered a chain reaction or domino effect of other side effects, including total insomnia, constipation and bloating. The body can handle one or two side effects but once you get up to three or four then you really start to struggle.

However, the first dose is generally about learning to manage side effects. Duly, things improved with successive doses. After two months of fortnightly chemotherapy, I enjoyed a break over Christmas. I began radiotherapy in the New Year. You do not generally feel anything during the delivery of radiotherapy in spite of how powerful it is. My side effects were minimal due to the fact that it was targeted and low dose. The most noticeable one being painful swallowing, which was manageable with soluble paracetamol.

My final PET scan was organised three months from completion of treatment and I was formally declared in remission. From now on, the focus would be on looking after myself in order to remain in remission.

The big question for the 21st century is whether a cure for cancer is attainable. Each passing week generates a new story heralding the arrival of a wonder drug round the corner. The United States has invested over $200bn (£160bn) ever since Nixon declared war on cancer in 1971. More recently, Obama’s cancer “Moonshot” programme will mean more investment in research.

The latest developments are showing great promise. Immunotherapy harnesses our own immune system and early results, even in terminal patients, have been very encouraging. Yet a cure for cancer implies a silver bullet. This appears increasingly unlikely in that each cancer is uniquely individual in terms of its genetic mutations and molecular structure. As Siddhartha Mukherjee – the oncologist and Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer – explains, cancer is essentially a “distorted version of our normal selves”.

Cancer demonstrates evolutionary characteristics as it develops. It adapts to the environment and even evades treatment. Cancer cells do not exist in a vacuum but instead are found in a rich micro-environment of immune cells and blood vessels. A Google Street View mapping of this micro-environment is required.

Personalised medicine may hold the key to the future with treatments ultimately tailored to each patient’s cancer. Thus, genome-based research holds the promise of new ways of diagnosing and treating cancer. Other research suggests that, in spite of countless differences, treatments targeting common pathways may offer a potential Achilles’ heel.

Integrating big data between genomics and clinical fields will play a key role with greater information sharing between centres. While translational medicine will be increasingly employed to translate laboratory findings into the clinical setting. This “bench to bedside” methodology will only speed up progress.

In spite of such exciting potential, good old-fashioned prevention remains preferable to a cure. Public health measures against smoking have demonstrated the importance of tackling root causes. Tackling air pollution, causative of a massive burden of disease as identified by the World Health Organisation, will be necessary.

Screening has been one of the key factors behind improving survival rates with cancers diagnosed earlier. At the same time, we are learning to balance over-diagnosis with under-diagnosis. For example, we are beginning to understand that some types of breast and prostate cancer are relatively harmless while others are dangerous.

Yet even as we continually improve treatments, who will benefit from such increasingly costly advances? Much of the world does not have access to decent healthcare. Obamacare fell a long way short of the kind of public, universal healthcare that the US so badly needs. Yet even this is likely to be dismantled by the Trump administration. Similarly, the NHS is undergoing increasing privatisation with the concomitant expansion of private health insurance.

Who will live and who will die and who gets to decide? One of the biggest challenges in 21st-century global healthcare will encompass this struggle between the private and public provision of healthcare.

Youssef El-Gingihy is the author of ‘How to Dismantle the NHS in 10 Easy Steps’ published by Zero books. Follow him @ElGingihy

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies