The Bank is being too optimistic again but there are some glimmers of hope

The frustrating part of the recovery is its slow pace

Not good but not awful. Successive editions of the Bank of England's Inflation Report have consistently underestimated inflation and overestimated growth, so it should come as little surprise that the latest one should follow the same pattern. Some day, maybe some distant day, the Bank will find itself revising its inflation forecasts down and its growth ones up, but we are not there yet.

Those of us who expected inflation to be below the 2 per cent mid-point of the target range by now have been proved wrong, and it is small comfort to say that the Bank economists got it wrong too.

As for growth, well, even allowing for the under-recording of what is actually happening, it is disappointing. The Bank revised down its forecast for this year yet again and while it revised next year up a touch, past experience says we should wait and see.

The Budget is now only five weeks away so that will be the next point of focus. A host of dispiriting questions hang over it. Will the Office for Budget Responsibility take a more optimistic line on growth? Can the Chancellor retain credibility for the deficit-reduction programme, given the failure to cut the underlying deficit to any significant extent this year? Can monetary policy be eased further, given the damage that present policies have done to pension funds and ordinary savers?

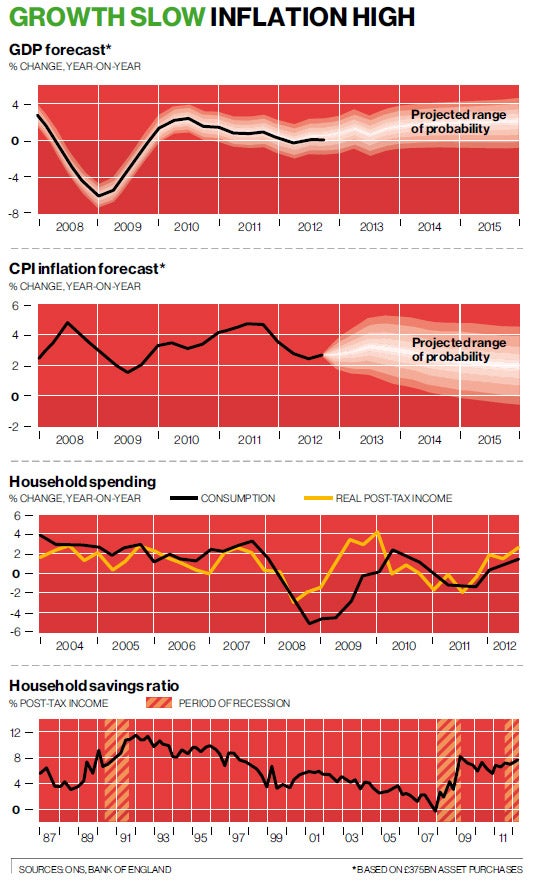

Actually if you look at the data flow as a whole I think there are some quite positive signs coming through that growth is indeed picking up, but it is a disappointingly slow process, as you can see from the top fan chart. The Bank pioneered these charts, which aim to show the range of possible outcomes, with the outer edges of the fan defining 90 per cent confidence. In other words, nine times out of ten the outcome should be within the shaded range. If you take the mid-point of the range, the Bank economists expect growth to be about 1.7 per cent by the end of this year and 2 per cent by the end of next. Not brilliant but not dreadful.

Inflation is pretty bad, and it is almost as though the Bank has given up on what was supposed to be its principal objective: it now does not expect inflation to get back to the 2 per cent mid-point for another two years. Part of the reason for the adverse outlook is what is called administered prices: prices that are set by government policy rather than market forces. Thus the increase in university fees has pushed up overall education costs by some 20 per cent. The environmental costs heaped on to our utility bills have increased these over and above the wholesale cost of energy.

You may or may not approve of the rise in university fees or the government's environmental policy but the Bank calculates that these policies are adding about 1 percentage point a year to inflation and that this effect will continue for the next few years. So were it not for government policy, inflation would be below 2 per cent and living standards, instead of falling or at best being stagnant, would be starting to nudge up.

So can living standards rise against such headwinds? Sir Mervyn King was suitably downbeat about the prospects, and separate figures showed that living standards are now back to the level of 2003. Looking at the overall numbers I think there is no question that the squeeze will continue for a while yet. But have a look at the bottom two graphs, for they paint a slightly more positive picture.

One shows household consumption and total real household resources. Both have started to push upwards. This rise in resources may come from more people in a household working, or working longer hours, or from lower mortgage costs, rather than increased pay. But it does seem to have enabled consumption to climb a little.

What also seems to be happening is that the retail sector has responded to the squeeze on incomes by cutting its costs, running special incentives, and generally coping in a sensitive way with the fact that many customers are struggling. It may be a bit unfair on our political leaders, but you might say that the private sector is trying to cut prices and so offset the rises in prices that the Government is imposing.

The other graph shows savings. As resources have increased people have decided to set aside some of the cash for savings, which are now much higher than they were during the boom years and back to 1997 levels. You could say that we have as individuals corrected the errors we made during the boom. The bad news here is that many people will have to save for several years to get debts under control. The good news is that in total we have got savings back to a reasonable level.

There are other chinks of light. Retail sales are not bad, in January up nearly 2 per cent year on year. Car sales were up 12 per cent in January on the previous year, which is pretty stunning. House prices remain broadly flat but there was a big rise in first-time buyers, which suggests that the special scheme to increase the supply of mortgages may be working. Shares continue to climb, which must have some feed-through into final demand.

And as is now generally recognised, employment is still climbing and unemployment falling, notwithstanding the dire predictions of some commentators. It is at best an uneven performance, and the further away from London and the prosperous South-east you get, the greater the pressures. But it is not a dreadful one.

So what should we look for next? There are two really important bits of data coming up. One is employment. If the great engine of private sector employment is still running, then we can relax a little. If it falters, that would be profoundly worrying.

The other will be the public accounts for January, important because January is a big month for tax receipts. If tax revenues are all right then that will tell us that the economy is still growing. If there is a shortfall, then there is trouble. But the detail of the shortfall will matter too, because it may be the result high-earners cutting their incomes, rather than general weakness. A difficult few weeks lie ahead.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies