Hamish McRae: Markets' merry Christmas despite triple-dip talk

Economic View: Monetary policy has started to be counterproductive as it has all sorts of negative effects

The markets are moving into the festive season in appropriately festive mood. The FTSE 100 index is within half a percentage point of its yearly high. The pound is within a quarter of a cent of its high against the dollar and decently up on the euro over the year. True, the UK 10-year gilt yield is back to 2 per cent, exactly where it was a year ago, after dipping to 1.5 per cent during the summer, but by long-term standards yields remain exceptionally low.

There are, of course, many commentators who expect a sharp reversal of fortune next year. For example, Andrew Smithers of Smithers & Co has been arguing that sterling is woefully overvalued and that equities are too expensive relative to their long-term averages. Some economists are warning of a "triple dip" to the economy and if there were such an outcome the UK's AAA borrower status would presumably be lost.

If may well be that come the new year these negative sentiments will ride to the fore again, but they do not seem to be having much impact on financial markets. In terms of published GDP, the pessimists of a year ago may turn out to be right – we will have to wait to see by how much the figures are revised – but as a predictor of market movements they have been quite wrong.

So why this general optimism? There are two broad arguments:

One is to accept that the UK economy, along with that of other developed countries, is still in the early stages of recovery. So you would expect uncertainty at this stage, with some things turning out better than one might expect, such as the level of employment or car sales, and some worse, including inflation and those GDP figures.

If you start from there, then any setbacks can be seen in the context of an expansion that will last another six or seven years, maybe longer. There is such a thing as the economic cycle, but the next downturn may not come until the late teens and may be quite mild when it does.

Consequently, if there are three or four more years of flat house prices values will be back to their long-term relationship with incomes. Companies can look forward to several years of overall growth. Employment will continue to grow, and assuming inflation does soon come under better control, living standards can start to rise again.

There are, of course, many things that might go wrong. These include the mismanagement of US fiscal policy, prolonged recession in much of Europe, a spike in energy prices, and so on. But the general outlook is positive, the specifics negative, and it would seem reasonable to assume that eventually the general will come out on top.

That seems to me to be a common-sense approach and there is nothing wrong with that. There is, however, another group of arguments that could explain present market buoyancy and produce a less positive conclusion. They run like this: since the financial crisis, governments and central banks have used war-time financing policies to combat a peace-time crisis. While you can justify such tactics in an emergency, these policies have been carried on for too long. As a result they have not only become less effective, they have also started to have unintended consequences.

So the recovery in house prices and the present strength in equities are more a function of a flood of money with nowhere else to go.

That flood will continue awhile yet and not just here in the UK. The European Central Bank has committed to buying distressed sovereign bonds if that is needed to save the euro. The Federal Reserve looks like adopting an unemployment target of 6.5 per cent, albeit as a temporary measure, before it starts to tighten significantly. There are stories that the Bank of Japan, now the election is over, will be pressured into new ways of combating deflation, a shift that has already led to a sharp rise in Japanese share prices. And here we will in the summer have a new Governor of the Bank of England, who has floated the idea of a move to a money GDP target, rather than just an inflation one. Some see this as a way of justifying an even more expansionary monetary policy.

Seen in this light, the present strength of equities is more a reflection of confidence that central banks will keep on printing money rather than confidence in the solidity of the recovery. Which view is more valid?

My own feeling is that monetary policy has started to be counterproductive as it has all sorts of unintended, negative effects. These include damaging pension funds, denying savers any return and encouraging risky investments in the hunt for yield. As a result, shares are not particularly cheap by historical standards.

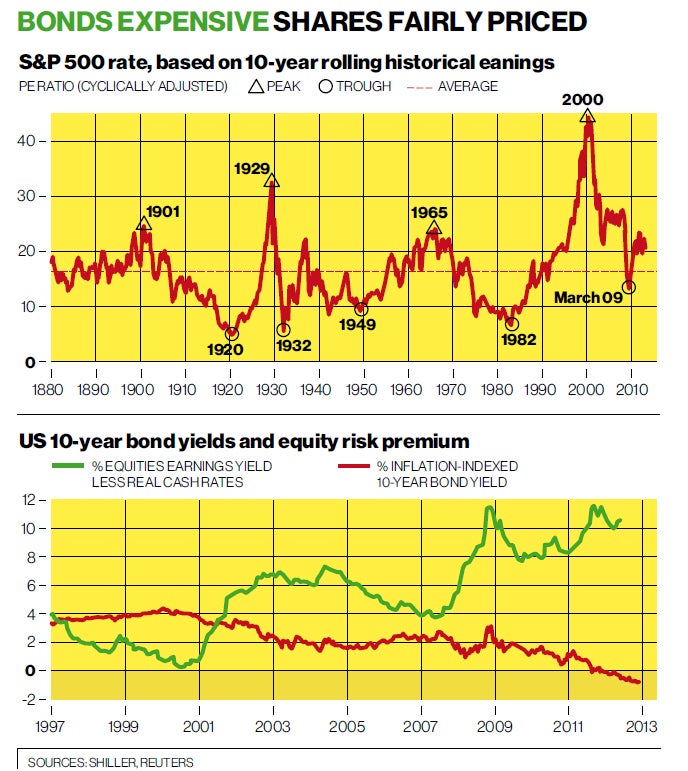

You can see the price-earnings ratio of US shares, going right back to 1880, in the top graph – I am taking American data as it is to hand, but the same lessons would apply to UK or European securities. Back in March 2009 they were indeed very cheap, as some of us wrote at the time. Now they are above their adjusted, 120-year average.

On the other hand they are not as absurdly valued as US bonds. The bottom graph shows two ways of looking at the relationship between the returns on bonds and equities. The red line shows the real yield of 10-year bonds, which has now gone negative: interest is below inflation. So they are by just about any standards a dreadful investment. The green line shows the US equity risk premium: the gap between the earnings yield of companies and the real yield on cash. On this basis, shares are very cheap.

Conclusion? It is easy to agree that prime bonds, be they US, UK or German ones, are artificially high – ie, long-term interest rates are artificially low. I think a 30-year bear market in bonds may have begun.

It is hard to agree about share values – but where else do you have some sort of protection against inflation?

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies