Hamish McRae: A double dip, then recovery. But what will drive our future growth?

Economic Life: We assume that financial innovation happens in the West, but it may move the other way

After the "pause", "double dip" or whatever you choose to call it, what then? The question has to be asked because there is mounting evidence that there will be several more months before the recovery will be secure.

That is not certain, of course, nothing ever is, but we know this much. All the major economies came off the bottom some time last year. True, some turned earlier than the others, and the UK was relatively late, according to the official figures, and a few smaller countries are still lagging. But the turning point is past. We know, too, that something seems to be going wrong now. Growth in Germany stalled, and unemployment there is rising. Eurozone economic sentiment fell. And the US has been stunned by some dreadful consumer confidence figures this week and employment remains weak.

What we don't know is how long this second phase will last, or whether it will deteriorate into a second recession, the technical definition of which would be another two quarters of negative growth. My own guess is that most major countries will avoid that, though some will experience another quarter of decline before the recovery picks up. The point surely worth making is that we should be neither surprised nor alarmed when this happens. It is normal; trouble is normal, if not nice.

There is a further point to be made. Demand in the world economy is now driven as much by the emerging economies as by the old developed ones. China passes Japan about now to become the world's second largest; India, while still a lot smaller than a large European economy such as our own, is roughly the same size as that of Canada and Spain. China is growing at about 10 per cent a year, India at perhaps 7 per cent. So in calibrating the global recovery, we need to factor in the contribution of the large emerging nations.

More of that later; first, back to our own situation. There will be a string of negative factors hitting the economy through the summer. There will be some tightening of fiscal policy, though not a lot, whoever wins the election. By the end of the year interest rates will, on the balance of probability, have started to rise, and there will be no significant further quantitative easing.

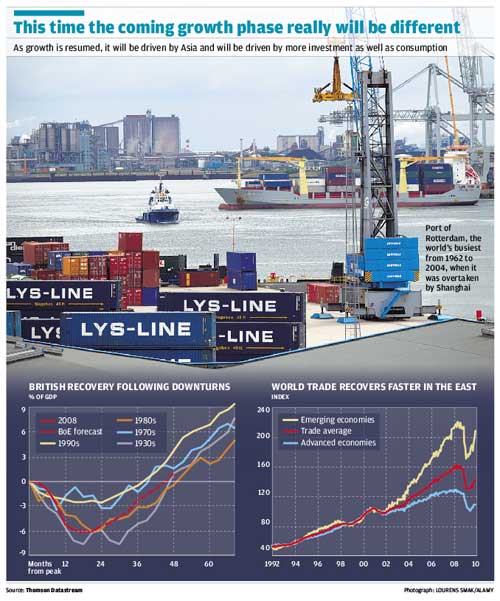

So lots of negatives. But look at the first graph. It shows the path of the UK economy during four previous downturns: the 1930s, the 1970s, the 1980s and the 1990s. Then against that it plots this recession: what has happened to date and where the economy is projected to go according to the Bank of England's latest Inflation Report. Or rather, this is an interpretation of what the Bank thinks, based on the central point of its famous fan charts and on the assumptions of unchanged interest rates. Jefferies & Co, the US investment banking firm that produced this data, notes that this new Bank forecast is realistic and that the expected profile of recovery is now very similar to that of previous cycles.

I find this pretty convincing, and if this profile does indeed prove more or less right, this recovery will be "normal" indeed. In terms of the depth of the downturn it will be very similar to the 1980s, while in terms of the duration it will be a touch shorter. It is not a great prospect: we do not get back to the past peak of output until the end of 2011, and the recovery in the next few months will be muted. If, as I expect, monetary policy will have to be tightened later this year, the pull-out will be even slower than suggested. But this prospect is not really dreadful – just a bit glum.

The question that I find most troubling, however, is what happens after 2011. Where will growth come from in the developed world through the next expansion, the one that will run from 2012 through to, say, 2018? We have this double-dip and we get growth going again. What then?

We do need to make a distinction here between the "old" and "new" worlds. As you can see from the second graph, through the 1990s world trade developed on parallel lines in both developed and emerging nations. Then the graphs diverged. "They" shot ahead; "we" plodded on. Shanghai took over from Rotterdam to become the world's largest port. Then over the past year, while trade in both parts of the world has taken a massive blow from the recession, the emerging world has bounded swiftly back, while the rest of us have struggled to regain the lost ground.

I think this is a taste of what is to come. The emerging world will drive growth through the next expansion. As a result the growth phase will have a number of characteristics that will make it different from past ones.

Five ideas: First, the balance between consumption and investment will be different, with the latter more important than in previous cycles. Yes, viewed globally, consumption will be the most important driver of growth; it always is. But investment, particularly in infrastructure, will be tremendously important too.

Second, and leading on from that, it will be an expansion characterised by huge demand for energy and raw materials. There will be a lot of infrastructure going in, and that needs energy, concrete, steel and so on. So energy prices will remain relatively high right through the next decade. Raw material producers everywhere will benefit.

Third, the weight of financial activity will shift eastwards. In North America and Europe the entire growth phase will be spent fixing things. There is a lot of that to be done: fixing public deficits, fixing personal finances, recapitalising companies. That has to happen, and it will require financial skills, but it will not be exciting business. The excitement will be elsewhere.

Fourth, savings will no longer flow from Asia to Europe and North America on the scale they have in the past. Asian savings financed the last boom and many owners of the assets these savings acquired have lost money as a result. That mistake will not happen again, or at least not on that scale. As a result there will be significant shifts in currencies, with emerging market currencies climbing vis-à-vis the rest of us. Most obviously the Chinese yuan will rise somewhat, though in a controlled way.

Finally, the world of ideas will shift too. For example, we assume that financial innovation happens in the West. So Shanghai invests in a stock exchange on western lines; the US model of hedge funds spread from New York to London, and now to Hong Kong and Singapore. I am not sure that will happen during this expansion; indeed, innovation may move the other way.

I realise that it may seem a touch premature to be discussing what this growth phase will look like when it has hardly begun. But it seems to me there is a real danger that we in the developed world will spend the next few years focused on our past mistakes: how to stop another banking crisis, how to patch together the eurozone, how to pay off our debts. As we do that, we will miss what is happening elsewhere, and, in particular, fail to see why this expansion will be different from past ones – and accordingly there will be new and different lessons to be drawn.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies