Hamish McRae: Carney must take a sober approach to credit problem

Economic View: Should they attempt to compensate for past errors with painkillers and a suitably calibrated dose of the booze?

Should it be cold turkey or hair of the dog? William McChesney Martin, the chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1951 to 1970, is credited with the remark that the task of the central banker was to take the punch bowl away just as the party was getting good. But the world's central bankers failed to do that during the long boom and were complicit in creating the bubble that burst in 2008. I expect that economic history will be pretty harsh on them.

But to say that gives no guide to what they should do now. Should they do relatively little and just wait for the hangover to cure itself in the normal path of time? Or should they attempt to compensate for their past errors with a combination of painkillers and a suitably calibrated dose of the booze?

The broad thrust of central banking policy, certainly after an Italian, Mario Draghi, became head of the European Central Bank, has been to follow the second option. But while it averted catastrophe, and the central banks should take credit for that, it has not been particularly effective. They printed more money, they pushed down interest rates, they bribed and cajoled the banks to lend more, but not a lot has happened.

There has been a modest recovery in property prices in most markets – though not in those where the party was most chaotic, such as Spain – and recently there has been a recovery in share prices. The money has to go somewhere, and since people have realised that lending to governments at below the rate of inflation is not a great idea, that money is now going into equities.

But the principal aim of the policy – to get growth going again – has proved elusive. So now there are calls for yet more measures to enable economies to achieve lift-off.

Enter Mark Carney, governor-elect of the Bank of England, who faces the Treasury Select Committee today.

He was not complicit in the excesses of the past, and that is important. Canada, where he is head of the central bank, was one of the few developed countries that did not have a banking crisis, and though there were some elements of excess in the property market and elsewhere, the country came through the global recession in pretty good shape. Canada was lucky; but Canadians were wise.

Expect every word of the new governor to be picked over for implications for markets. That is how people make money. So some hints that he gave at the Davos forum that bankers should promote growth have already triggered some weakness of sterling and maybe some weakness in the gilt market. If the Bank of England is to seek changes in its mandate, perhaps to ease the inflation target, then expect sterling and gilts to go down.

Actually he is far too clever to incline toward the keep-the-drink-flowing school of central banking, partly because that approach is discredited, but more because to do so would be self-defeating.

Inflationary expectations in the UK are higher than in the United States and Europe, and that is already influencing growth.

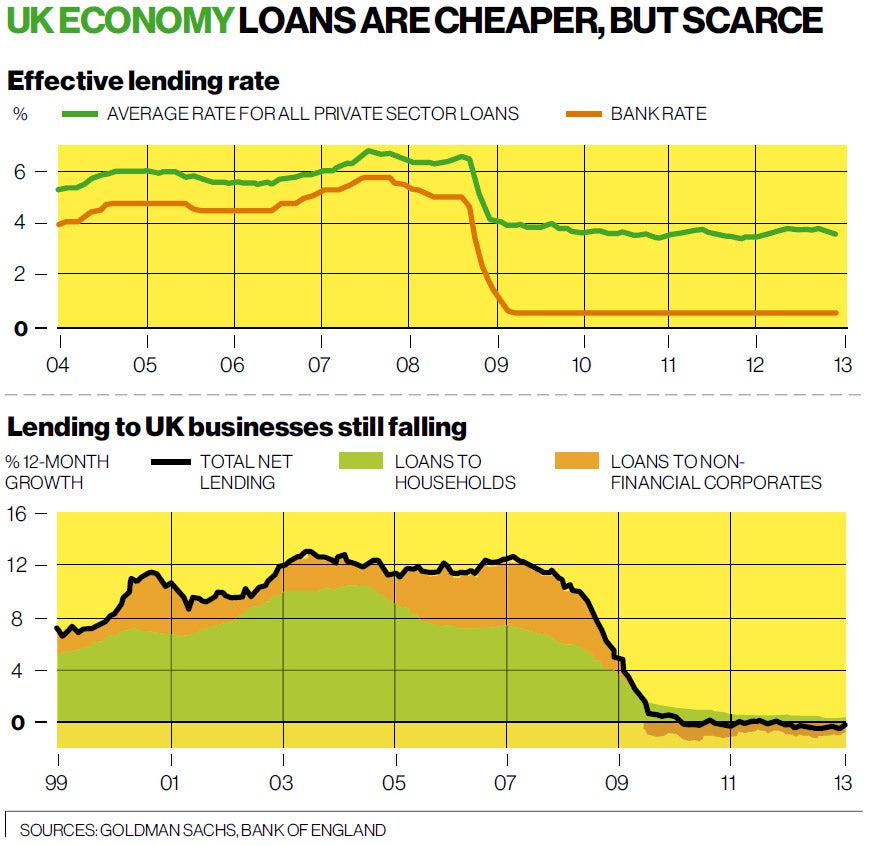

But there is a problem with the supply of credit, and it will be interesting to see what hints we get about his approach to dealing with that. You can see the problem encapsulated in the two graphs.

The first shows official interest rates and the average cost of a new loan to the private sector. As you can see, a bit of the fall in the cost of money has fed through in cheaper loans, but most has been absorbed in wider margins. Why? There are a number of reasons, and it is hard to know how much weight to attribute to each.

One is that the cost of money to the banks has not fallen in line with official interest rates. People don't want to accept 0.5 per cent, or whatever their bank is offering, and they shop around for a better rate, maybe buying some short-dated bonds instead.

Another is that banks have to constrain their lending to comply with increased capital requirements, so there is little competition for new customers.

The foreign banks that used to be a big part of the UK lending scheme have gone home. And banks have so many bad loans on their books that they have to charge more to reliable customers to make up. Not only are loans not as cheap as they should be, or to put the point another way the very low official interest rates have become ineffective, but loan volume has collapsed.

You can see that in the other graph. Lending to individuals is just about positive, with more money going out than coming back. But lending to companies has gone negative: the net amount of money being paid back is greater than the net amount of new loans.

Again, there are a number of reasons for this. Some of it is falling demand for credit, typically because a company has heard of banks suddenly calling in loans and not wanting to be beholden to them.

Another is that banks have so many bad debts that they are twitchy about lending more. (They are particularly worried about lending more on property.)

As for individuals, a lot of people are paying down their credit cards and mortgages as fast as they possibly can, and who can blame them?

There is, however, a problem on the supply side, some of which is a result of the new banking caution – statistically loans to small businesses are among the most risky – and some which is not.

So efforts to clear blockages in lending, such as the funding for lending scheme promoted by the Bank, are welcome, and seem to some extent at least to be working. One of the interesting things tomorrow at the Select Committee will be to see how much further Mr Carney feels these unconventional ways of boosting credit can go.

But we should be careful about changing the mandate of a central bank. As Goldman Sachs argued in a recent paper, the Bank of England can do more to ease credit within its existing mandate. Keeping the present mandate would be a signal that when eventually the party does get good, it will indeed take the punch bowl away.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies