Hamish McRae: Downbeat and daunting with turmoil aplenty, but a recovery will come one day

Economic Life: The IMF has upped its forecast for growth. The US seems to be moving again. And if China hit a growth pause, it would take the pressure off oil and commodity prices

January is always a gloomy month but the past few days have seen an even more downbeat start to the year than usual. There were the widely publicised growth figures for the final quarter of last year – or rather non-growth figures, for the stats said that the economy had shrunk by 0.5 per cent during the three months.

Then there was a speech by Mervyn King warning about the further rise in inflation and the fall in living standards that was still taking place. There is all the debate about the first rise in interest rates. Add in the soft housing market, the rise in VAT, the prospect of cuts in spending in the coming financial year, public sector job losses – it is quite a daunting prospect.

Is it plausible that the UK will be the only major economy to experience a double dip and what should we be looking for in the run-up to the budget in March?

To get that final quarter fall in GDP out of the way, I should just reiterate my own view that these figures will prove to be wrong, and that when all the data is assessed in another 18 months' time, it will be shown that either the decline in output was much smaller or that it was flat. My reason for thinking this is that other data suggested there was indeed some slowing of growth in October and November but the weather-related fall-back in December would have to be enormous to push overall output so far into negative territory. We will get a better feel next month when we have the other estimates of GDP, the income and the expenditure measures, but given the huge difficulties in service sector output, we won't really know for sure what has happened until well into next year (the output measure always comes out first and Britain is unusual in publishing data quickly. In theory, it plus the income and expenditure measures should all tally but in practice they always vary a bit. Then all figures are revised, sometimes several times).

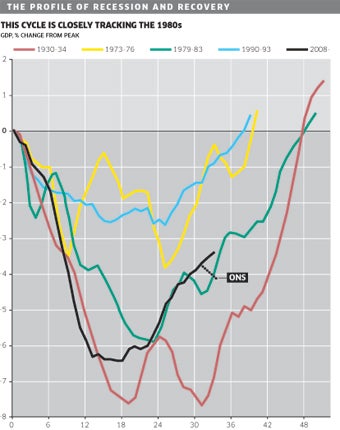

If you stand back from this debate and look at the bigger picture, a slow but solid recovery is in place. The graph shows the most recent estimates from the National Institute of Economic Research of this recession, which shows growth in the final quarter, together with the new estimate from the Office for National Statistics showing the decline. And this cycle is plotted against the three main post-war recessions, those of the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, together with the 1930s recession.

As you can see, what has happened this time closely resembles the experience of the 1980s. Output did dip a touch deeper this time (though if you exclude the boost from North Sea oil, the 1980s was actually worse) but now is either a little above the 1980s profile or a little below it. But as you can see, you frequently have pauses on the path to recovery and the big message, surely, is that once growth is securely re-established it is overwhelmingly likely to continue. But it is worrying, nonetheless, because the headwinds will be strong and there is a still a long way to go before the economy reaches its previous peak in output. On the 1980s profile it will be the back end of 2012 before we do so.

The headwinds include higher commodity and energy prices, driven mostly by demand from China, personal and national debt (of course), the upward movement of long-term interest rates world-wide, and the weakness of the UK's single largest export industry, financial services.

Against this is the general global recovery. The International Monetary Fund has just upped its forecasts for growth this year. The US, after a wobble last autumn, seems to be moving forward decently again. Germany is doing very well indeed. And if – not impossible – China were to hit some kind of growth pause, then at least that would take pressure off oil and commodity prices.

So, what else should we look for? Top of my own list of concerns is the rise in long-term interest rates. If you look around the world, governments everywhere are starting to have to pay more to borrow. Obviously the weaker eurozone nations have to do so, and I suppose a downgrading yesterday of Japan's debt by Standard & Poor's is unhelpful. Actually, I see that as a shot across America's bows. It is perfectly plausible that US debt will be downgraded this year from its present AAA status. That would matter more as a symbol than anything else – remember how the rating agencies gave AAA ratings to rubbishy bonds tied to the US house market – but a downgrade might set other things in motion. China is now the largest buyer of US sovereign debt.

If long-term rates rise sharply worldwide, the costs of borrowing here will rise too, and not only for the Government. Fixed-rate mortgages would cost more; indeed, you can see that already happening. I sense that we may be starting a long period of rising rates, something that will last 10 or 20 years, and will look back on this period of very low rates as an aberration.

This will be associated with sovereign defaults: countries admitting they cannot pay their debts as they fall due. There have often been such defaults in the past but these have, in recent history at least, invariably been by developing countries. Now it will be developed ones. It does not add to the sum of human knowledge to list the most vulnerable nations here but you see the point. Why lend money to a country that might not repay for a small extra interest margin when there are others that you can be very sure will repay? Better to sleep easy overnight.

If the past five years have taught us anything, it is that financial markets have been poor analysts of country risk and currency risk. Leave aside Greece and Ireland; the turmoil of the euro over the past year was not on the mainstream radar – it was only a few economists and columnists who warned of the dangers.

Now I happen to think that the euro will hang on for a while yet but I am concerned by the comments of Nicolas Sarkozy and Angela Merkel in Davos yesterday, both of whom pledged never to let the euro fail. That is a sell signal if ever there was one – touch of Gordon Brown's pledge of ending boom and bust.

So the difficulty for us here in Britain this year will be to keep our cool in the face of a series of dispiriting news stories, with obvious headwinds here and unpredictable headwinds abroad. But look again at the graph. Recoveries take a while and in their early stages they are not much fun for anyone, but we do clamber up somehow.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies