Hamish McRae: Forget what happens in May, it's the long term that matters

Economic Life: We will get a rise in short-term eurozone rates soon, maybe next month, but it is easy to exaggerate the real impact of such a move

We should not worry about small increases in short-term rates, here or anywhere else, derailing the recovery. What we should be worrying about is much larger increases in long-term rates. OK, that might seem a bit stark, but bear with me.

We have just had another "no change" decision by the monetary policy committee here in Britain, so UK rates will probably stay on hold till May. By then the committee will have had the Budget and the first-quarter GDP figures, and everyone will have a clearer idea of the disruption to the world economy likely to be caused by the tensions in the Middle East. Barring some new shock, though, we can bank on the MPC putting rates up by 0.25 per cent in May.

Does that matter? There will be the inevitable headline impact of the first stage of a reversion to normality, but the net impact on the economy is likely to be quite modest. You have to remember that though borrowers might have to pay a bit more, savers will increase their income. Calculations by Ben Broadbent and Kevin Daly at Goldman Sachs suggest that the impact of changes in interest rates on household income is small compared with that of other factors, including higher commodity prices and taxes.

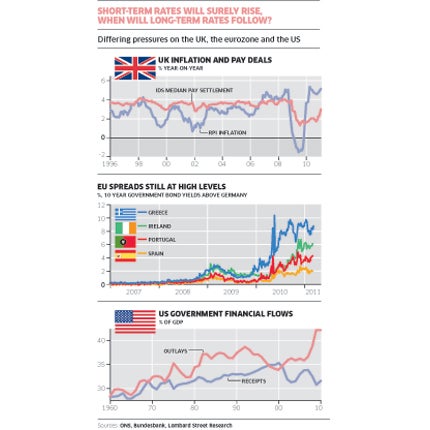

As you can see from the first graph, pay increases have fallen far below inflation as measured by the retail price index, and although they have recently picked up a little, they are still well below the average from 1996 to 2008. The authors comment: "The direct effects of rate hikes on household income and default rates simply aren't big enough, at the margin, to warrant the degree of concern often expressed about them."

Now I quote that because, as you may have noticed, Ben Broadbent is the new member of the MPC. It is a good appointment because he will bring common-sense judgement to the committee, having been broadly right in his assessment of the UK economy through most of this cycle. He points out in this paper that the growth in the UK and elsewhere will be driven by investment, not consumption.

What about Europe? We are going to get a rise in short-term eurozone rates from the European Central Bank quite soon, maybe even next month. That will hit the headlines. But, as with the UK, it is easy to exaggerate the real impact of such a move, even in the most indebted countries.

Take Ireland. A rise of short-term rates from 1 per cent to 1.25 per cent will not be helpful, but the problem of Ireland is not the cost of short-term money, which by any historical standards will remain very low. It is the cost of long-term money. That leads into a discussion about the mounting tension within the eurozone, a tension which is coming to a new head.

The new Irish finance minister, Michael Noonan, has a mandate to try to negotiate a better deal and you can argue that the interest rate on the Irish bailout, at a little under 6 per cent, is high compared with the cost of funds to the largest participant, Germany, of around 3 per cent. But the open market rate at which Ireland could borrow is somewhere around 9 per cent, assuming it can get the money at all, so while in one sense Europe is making a profit on its loans to Ireland, in another sense it is subsidising it.

Would you lend to Ireland at 9 per cent? It sounds like a great deal, until you hear that "the bondholders need to take a haircut", which is a cute way of saying they won't get back their money in full. Dare you take that risk, perhaps on behalf of pensioners, in return for the somewhat higher interest payment? Lend money to Germany and at least you know you will be repaid in full on the due date.

What has happened to Irish creditworthiness has also happened to that of Greece and Portugal. You can see that in the middle graph, which shows the premium that those three countries, plus Spain, have to pay over Germany for 10-year loans. For Greece the game is over. Tax revenues are collapsing, and even if they were holding up it could not possibly pay that premium of 9 per cent more than Germany: an interest rate of 12 per cent in all. For Portugal, well, expect it to go for an emergency loan soon. Even Spain has to pay 2 percentage points more than Germany and its debt has just been down-rated.

You do not need to delve into the intricacies of the forthcoming eurozone summit about the success of the present bailout fund to see that the present situation is unsustainable. There will be a mess. That is easy to see. What is much harder to try to think through is what a default by Greece might do to bond yields more generally.

It may be that people would say there is no relationship between one or two eurozone defaults and the creditworthiness of the eurozone as a whole. It may even be that the rate at which Germany can borrow would come down as people looked for a safe haven for their savings. Or it may be that there would be a general perception that government bonds in general were not a great place to put one's savings and that even the most creditworthy would have to pay more to borrow.

The big news for the bond markets this week, bigger by far than the machinations about eurozone sovereign debt, came from Pimco, the world's largest bond fund. It revealed that it had sold off all its US government-related debt from its flagship fund. Its chief investment officer, Bill Gross, said of the recent bond action: "Nearly 70 per cent of the annualised issuance since the beginning of QE2 [the second round of quantitative easing] has been purchased by the Fed, with the balance absorbed by those old stand-bys – the Chinese, Japanese and other reserve surplus sovereigns."

But the QE programme has to come to an end, and suppose the Chinese stop buying? Last month China recorded a trade deficit, not a surplus. The final graph, from a report by Lombard Street Research, shows how far US tax receipts have fallen below government spending. Charles Dumas argues that net government debt, 68 per cent of GDP at the end of last year, could reach 100 per cent in five years' time and might then still be rising. He argues that this year's boom will be followed by a bust in 2012, as among other factors the US economy will be held back by severe budget cuts. But if there aren't the budget cuts, then maybe higher bond yields will be the thing that chokes off growth.

You see the point. In the boom years, governments have almost unlimited borrowing capacity. Then quite suddenly the mood can shift and they cannot borrow at all. It is harsh and in a way ridiculous. But that is human nature: we only lend to people who we think will pay back, and when we make mistakes in our judgement we overreact. Long bond yields for the US are artificially low. Common sense says the long-term interest rate cycle is about to turn up for everyone. And that matters much more than the decisions of the MPC.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies