Hamish McRae: Good job figures and bad growth or good growth and poor jobs - a transatlantic tale of two recoveries

Economic View: In the past, there may have been more people working in the informal economy

Washington DC – It is a tale of two recoveries. Here in the US, there has been strong growth of GDP, with the economy now 4 percentage points above its previous peak. But there has been very weak growth in employment, which is still 2 per cent down on the peak. In the UK, the position is quite the reverse. Even with the current rapid growth, we will not be back to the last peak until the middle of this year at best, yet employment is at a record high – nearly 2 per cent higher than the peak in 2008.

Why should this be? There is a further twist. If you look at headline unemployment, the figures are broadly similar. The US is now down to 6.7 per cent against our 7.1 per cent, but both countries are falling fast. In the US, however, many people are getting out of the jobs market altogether. The employment level, the proportion of people of working age in jobs, is down to 62.8 per cent, the lowest since 1977. That compares with 66 per cent in 2007. Had it remained at its 2007 level the unemployment rate would be above 11 per cent.

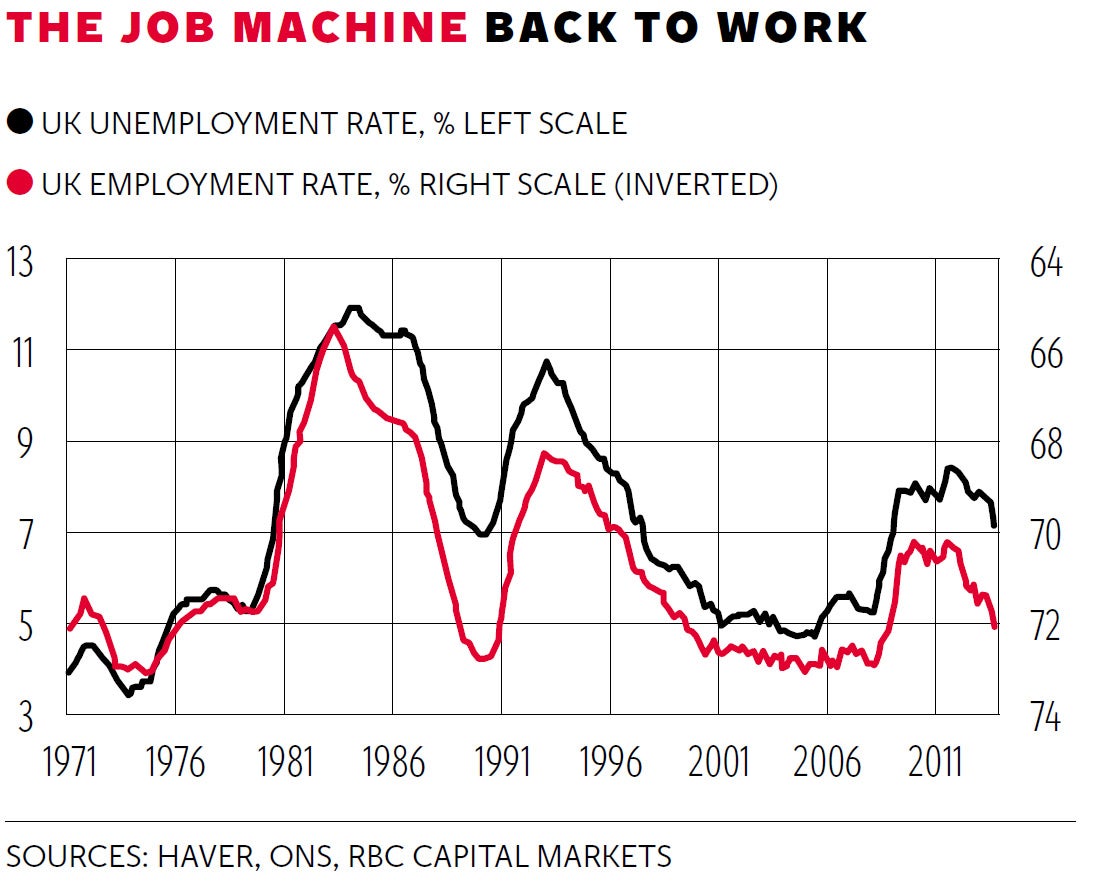

In Britain the position is reversed. More and more people are joining the labour market, partly as a result of inward migration but also because more older people are staying in work. Further, the UK labour participation rate is now 72 per cent, close to the record levels reached in the early 2000s, the 1970s and briefly at the end of the 1980s boom, and you can see from the chart showing the relationship between UK unemployment and labour participation.

The actual percentages are not directly comparable with the US, because they are calculated differently. But the basic point stands. We have almost the highest labour participation rates since the 1970s; the US has the lowest rates since then.

So what is the explanation? There is one knee-jerk answer that says that labour productivity in the US is still rising while in the UK is it falling. But that is not really an answer at all because productivity is calculated as a residual. You look at the official figure for GDP and the official figure for employment, and what pops out is the productivity of each person in a job. It does not tell anything about why more people in the UK are taking on jobs, or why fewer in the US are doing so. And if the figures for GDP and/or employment are wrong, the productivity calculations are meaningless.

My instinct is that a number of different variables are at work and the problem is knowing which of those matter and which are insignificant. Start with GDP. It is pretty clear that we are undercounting GDP growth in the UK and probable that the US is overcounting it. In the past, the Office for National Statistics has tended to revise upward its GDP numbers and the revisions have been particularly large at this stage of the economic cycle. All that nonsense about the "triple dip" was a result of a serious underestimate of what was actually happening. The US, in general, has revised its growth estimates down. The problem is that bad statistics can explain only a part of the discrepancy, at least in the UK. We may be underestimating the size of the UK economy by a couple of percentage points, but not by the amount that the employment numbers would suggest if previous productivity trends had been sustained.

Might the employment numbers be wrong, too? No employer is going to claim to have hired more people – and paid their national insurance – than they actually have, so the present numbers cannot be an overestimate. But what may have happened in the past is that there were more people working in the informal economy for cash, so at the peak of the boom there were jobs, and hours worked, that were not being recorded. The reason for this would be that the authorities have cracked down more successfully on employers that break the law. There is probably something here, though it is hard to see it being massive.

What we do not seem to have had in the UK, or at least not on the scale of the US, is the phenomenon of the discouraged worker. This is a huge worry in the States: the people who have lost their jobs, tried to find work and failed and, as a result, have simply stopped trying. The longer people are out of the jobs market the harder it is for them to get back in. For some, it has been a matter of retiring a bit earlier than planned. On the other hand, they may be doing informal work. There is a lot of debate about this here and the conclusion seems to be that the size of the informal or underground economy has indeed been rising, although no one knows by how much.

These uncertainties make it very difficult to frame monetary policy. The issue here is "the taper" – how quickly will the US Federal Reserve taper down its monthly purchases of US Treasury securities? The assumption is that this whole programme, their equivalent of our quantitative easing, will have ended by the autumn. The issue for us will be when the first rise in interest rates comes through. My best guess, notwithstanding these latest unemployment numbers, is that this will not be until November. The main reasons for this are that while current inflation remains low there is no immediate pressure to do anything, and the Bank of England has a bias towards an overly loose stance that has been reinforced by the arrival of the new Governor, Mark Carney. (There are a lot of worries about a Canadian housing bubble, the result of overly loose policies there.) Further, do not assume that the official UK unemployment figures will fall every month. The trend is solidly down but there may be a rogue number soon, suggesting that it has stopped falling.

The moral of all this is that we should never take any particular set of statistics at their face value but make a common sense judgement looking at the entire picture. And that is that on both sides of the Atlantic there is a decent cyclical recovery that gives us a bit of time to tackle the many longer-term problems.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies