Hamish McRae: Jobs are being created faster than at any time since records began – but wages, it seems, remain stubbornly low. What's going on?

Economic View: In the last boom we had false signals from inflation. Now we're getting false signals on pay

How do we tame the boom? For many people it is still hard to accept that there is a boom taking place. That is understandable, given the relatively slow recovery, given regional differences, and given the fact that there is still quite a lot of slack in the economy. It is reasonable, too, to mop up that slack as swiftly as possible. But we are racing along at the moment, racing as fast as I can ever recall, and all previous bursts of high-speed growth have ended in tears.

The labour market data is remarkable. The economy is creating jobs at a rate of 115,000 a month, the fastest since records began in 1971. The US, an economy five times the size of ours, is creating jobs at a rate of around 214,000 jobs a month – and that is the highest since 1999 and is considered to be a jobs boom. Now, it is true that we can suck in labour from the rest of Europe and we are doing that. It is true, too, that some of the people who have taken on self-employment or are working part-time may be willing to accept jobs or work more hours. It is true that as yet there is no wage inflation showing through in the pay rates, which remain negative in real terms. But however you slice it, this is a boom.

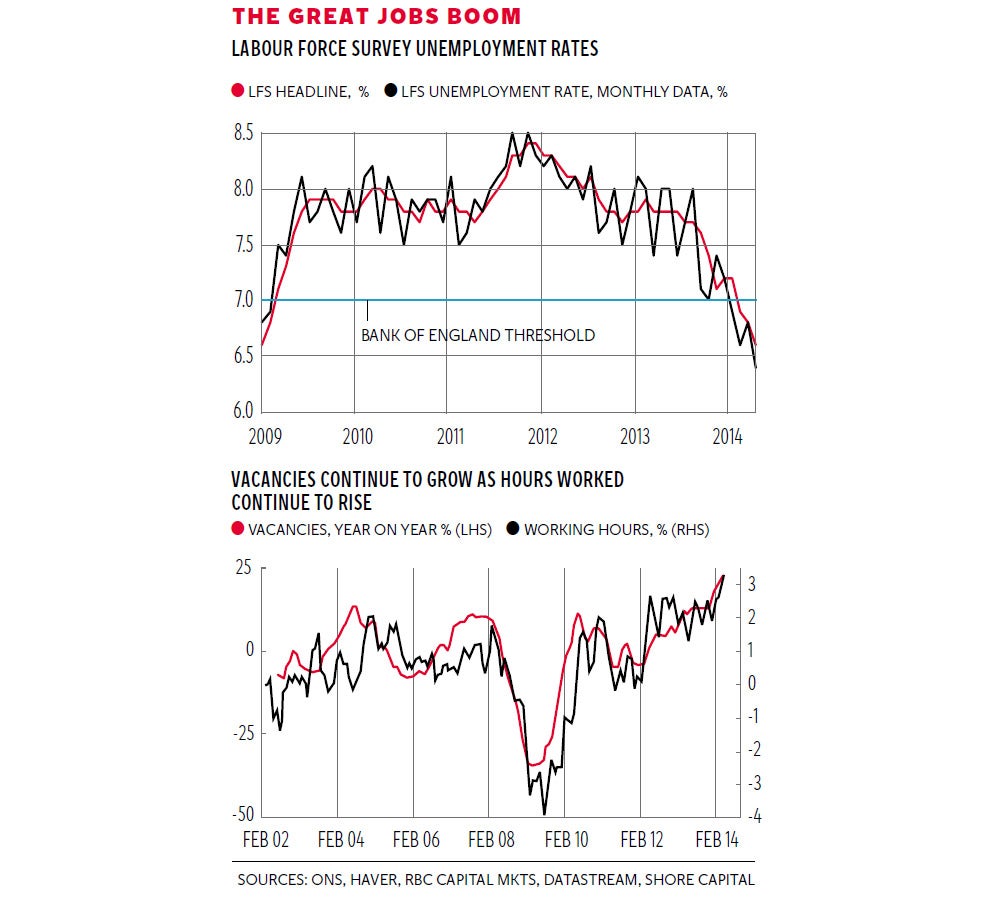

You can catch some feeling for this in the two graphs. First, there is the falling unemployment rate, shown both in the three-month basis and the more lumpy one-month basis. The former is the 6.6 per cent figure generally cited, but the latter is now down to 6.3 per cent. Remember, the threshold the Bank of England cited as the point at which it would consider increasing rates was 7 per cent. The way things are going we will be below 6 per cent by the autumn.

The other graph shows what has been happening to working hours, plotted alongside purchasing managers' surveys of employment intentions. As you can see, the two fit together, suggesting that working hours will continue to climb. Gerard Lane, an economist at Shore Capital, notes that with vacancies rising, wages – on past experience – should have started to rise too. This obviously has not happened yet, which leads to the real conundrum: why are wages not climbing?

We simply don't know. It is possible that the long period of recession and slack growth has changed people's attitudes to pay: better to have a job; now's not the time to push things; other people are in a worse boat; and so on. On the other hand, it is equally possible that pay is indeed rising but that a lot of it is not being declared: cash-in-hand bonuses, and payments to owners of small businesses that will not appear in the stats for another year or more. My guess is that it's a bit of both, but that rising pay rates could start to come through quite fast.

So how fast is the economy growing? Again, we don't really know. Officially it is around 3 per cent a year, though the latest quarterly stats put it rather above that. But total hours worked are up 3.3 per cent on a year ago. If that figure is right, then unless productivity has actually fallen, the economy must be growing at above 3 per cent. Assume only a modest increase in productivity and growth would be 4 per cent or more.

Intuitively, that sounds about right. I think, when the figures become clear in a few years' time, that growth in 2014 will turn out to be between 4 and 5 per cent.

If you accept even the possibility that this might be right, then it has profound implications for policy. The idea that interest rates should remain at 0.5 per cent will appear bizarre, just as the failure of the monetary and regulatory authorities to curb the 2003-2007 boom now seem bizarre.

At that time, we had false signals from current inflation, which seemed under control, and from OK‑ish fiscal deficit numbers, which seemed just about acceptable. So the authorities were lulled into complacency. They ignored the house price boom. Now we are getting false signals again, in particular from the pay statistics, and are being complacent about the need to tighten monetary policy. They are ignoring the job creation stats.

Now let's aim off a bit. I would not argue that there has to be an immediate rise in interest rates. It would probably be safer, on the balance of risks, to start increasing rates this summer, if only to make people aware that the present monetary circumstances are exceptional and that people need to plan for normality. But it would not be a disaster to wait until the autumn. And given the low current inflation numbers (notwithstanding all the fuss about cost of living), and what is happening in the eurozone, I can see an argument for waiting.

The housing market seems to have been damped down by the tightening of requirements for mortgages, and there is a decent case for waiting to see how these work through before using the interest-rate weapon. But we all know that in four or five years' time interest rates will be back to normal levels, and the practical difference between a new normal of base rates at 3-4 per cent and the old normal of 4‑5 per cent seems a bit academic.

Meanwhile I suggest that we celebrate the fact that the economy is creating so many jobs – or, rather, that the private sector is creating so many jobs, because the number of employees in the public sector is the lowest on a headcount basis since 1999. We must be doing something right.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies