Hamish McRae: Lower spending for sure but also a chance to steal a march on our rivals

Economic Life: There will, for the governments of half a generation, be little or no increase in their real spending: they will be like pensioners living on fixed incomes

August has proved so far to be, if not a wicked month, a dispiriting one. You might say it has been a month of realism, when just about everyone has come to recognise that clambering out of recession was always going to be a long slow business and that some sort of double-dip (you can argue about what that precisely means) was always on the cards. These columns have been arguing for some months that a pause in the recovery, even a period when things slip back a bit, has been a strong possibility.

But I think it is important not to get too obsessed by the cycle because there will at some stage be a recovery. Even if this cycle were to be as bad as the 1930s – and so far it is much closer to the early 1980s experience – the UK would be back to its previous peak in output by the end of 2012. What seems more important to me is the nature of the recovery and what the world will feel like beyond that.

One obvious difference will be that the world will have rebalanced towards the emerging economies, most obviously China and India. There has been huge attention to that and rightly so. But I think, as we come back from holidays and move into the autumn, there will be something else that will absorb all attention. It will be the changing nature of government itself, here in the first instance but also throughout the developed world.

In the UK we will be preoccupied by the spending review, the results of which will be unveiled on 20 October. It will be a shock. We are not used to being told by a government that there will no rises in spending, let alone that there will be severe cuts. That was not what was said at the election by any of the parties, though the departing Chief Secretary to the Treasury did have the grace and wit to leave a note to his successor to the effect that there was no money left.

That changes everything. It certainly changes the rhetoric. If you listen now to a Budget speech of Gordon Brown – any one, it doesn't matter which – you will find it already has a curiously dated tone. It is all about targets and spending and "we can do more". From now on politicians have to talk about having to do less.

The thing that brought this home to me was a report that came out last month on the finances of Scotland called the "Independent Budget Review", the work of a committee chaired by Crawford W Beveridge – and so becoming dubbed as Scotland's Beveridge Report.

Much of it is about choices over the next few years, but I was particularly struck by one passage, which sets the issue facing a nation of 5 million people in the wider debate that has to take place across the entire developed world. It is this: "Looking beyond the next spending review period, the analysis published by the chief economic adviser suggests that real terms budgets are set to decrease until 2015-16 and may not climb back to 2009-10 level until around 2025-26."

Think about that. If this is right, and it seems to me to be a realistic assumption, what will happen over the life of this parliament will not just be a once-and-for-all set of cutbacks, followed in the next parliament by a gradual recovery in spending. Rather there will, for the governments of at least half a generation, be little or no increase in their real spending. If they spend more on one thing they have to spend less on another. They will be like pensioners living on fixed incomes, maybe even falling incomes, as Japan's government has been for nearly two decades.

If you stand back and think about the nature of government since the Second World War, there has been a long period where governments have taken an increased responsibility for the welfare of their citizens. There have been areas from which governments have retreated, such as running national airlines or other commercial activities, and there has been a softening of the boundary between private and public sectors. But there has not been any retreat on central areas such as education and health. Indeed, globally, the world is still advancing on the latter front, witness President Obama's plans in the US.

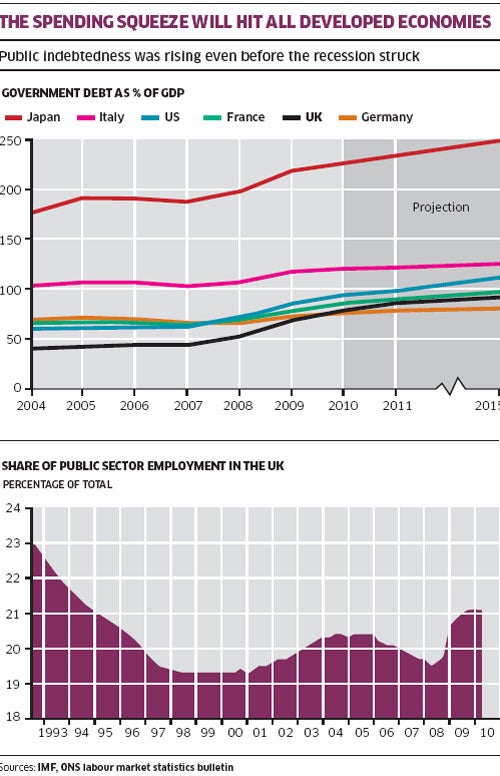

But the advance has only been possible because governments have been able to borrow. National debt was rising steadily in most of the main developed economies even ahead of the present downturn, as the first graph shows, when it should have been falling.

This is not just an issue for the UK. Taxes just about everywhere have been insufficient to fund spending. So now governments are being hit by a triple blow. They must cut spending to get back to a sustainable balance. They also have to service the additional pile of debt. And they do so against a background of an ageing population and the prospect of a falling workforce. In Japan, the most indebted nation, the workforce is falling by about 1 per cent a year.

A public sector that in 15 years' time will have no larger revenues, in real terms, than it has now, will have to shed staff. Can that be done? Well, here we can be a bit more encouraging, for as the bottom graph shows, it is possible to cut the public sector labour force as a proportion of the total.

That happened in the first half of the 1990s and despite the rise during Gordon Brown's big spending years, was declining until the recession struck. Remember that these figures show public sector employment as a proportion of the total, so as long as private sector employment climbs it is not so hard to cut back the relative size of the public sector. Looking ahead it would be plausible that the public sector might, in 15 years' time, employ about 15 per cent of the workforce rather than the present 21 per cent. If that sounds savage, note that it was down to about 19 per cent in the late 1990s.

Getting from here to there will be a huge task but it is one that cannot be ducked. The prizes will go to nations that manage this transition well – that preserve the core services of the state but at much cheaper cost. I think the mindset that sees an efficient state sector as a competitive advantage is the right one. If you look at it that way, the autumn spending round should not be seen simply as payback time for the spending errors of the past. Nor should it be "the last lot screwed up so we have to fix it", though there will be an inevitable political spin.

Rather I think we should approach it positively. There may be no rise in public spending, in real terms, for the best part of a generation. But that is the same for other countries too. It is a pity the UK has gone from the bottom of the public debt league to the middle, but we are not at the top. So we have a chance to reform the public sector so it does a more efficient job than the governments of our economic rivals.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies