Hamish McRae: Will messy skirmishes in currency manipulation lead to all-out war?

Economic Life: Is the UK policy of quantitative easing aiming to make it easier for companies to borrow money, or is it trying to weaken sterling?

The world is not quite engaged in a full-scale currency war but the rumbles of gunfire from border skirmishes are getting louder. In an economic downturn there is a practical advantage of having a relatively competitive currency: your exports are cheaper in foreign markets and as imports cost more, there is a shift towards home production rather than imports.

In boom years this matters far less: your own producers are running flat out and there are cost advantages in being able to buy cheaper raw materials. Indeed a strong currency is a useful discipline on companies to boost their productivity, as German firms have demonstrated.

But the developed world at least is now still facing slack demand, with the possibility of a double dip in the coming months. So countries that have experienced a fall in their currency have, in theory at least, been benefiting from that, while those with stronger currencies are being clobbered.

The issue is whether countries are deliberately pushing down their currencies, in which case we would indeed be heading into some sort of currency war, or whether such weakness is happening as a by-product of other measures taken to boost the economy. Put it this way: is the UK policy of quantitative easing aiming to boost the economy by making it easier for companies to borrow money and to put a floor under house prices, or is it trying to weaken sterling? Mostly the first, you might think. But the fact that the Bank of England is seen as more progressive on this front than the European Central Bank is cited by market watchers as one of the reasons why sterling is at a five-month low against the euro.

What happens to sterling vis-à-vis the euro is a sideshow in world terms. The big issue is the relationship between the dollar and the rest of the world.

This danger of a global currency war was noted by Dominique Strauss-Kahn, the IMF's managing director. He did not like the characterisation but did tell journalists in Washington yesterday that too many countries are pursuing policies that will boost their immediate economic fortunes but harm the global economy in the long term. There could be "no domestic solution to a global crisis".

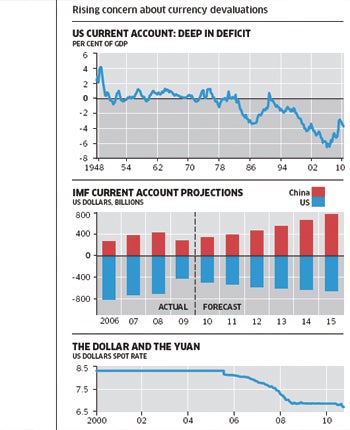

What is preoccupying the IMF is the tensions that occur in tough times. The imbalances that have led to these tensions have been around a long time. Take the US current account deficit, which reached 6 per cent of GDP during the height of the boom. Though it has narrowed somewhat with the slump, it has not been eliminated. As you can see from the top graph, derived from work by Lombard Street Research, the US has been in almost continuous deficit since the early 1980s. The IMF projects that it will remain in a deficit through to 2015 (middle graph).

How has the world's richest country been able to finance such a deficit? It has been able to borrow from countries that were selling it the imports, principally Japan in the 1980s and 1990s and recently China. The surpluses racked up by China are also shown in the middle graph. But this is not quite a symmetric relationship. Three years ago the US deficit was much larger than the Chinese surplus. That is still the case, just. But China's surpluses are likely to become greater than the US deficits.

Both sides in any unbalanced relationship must take some of the responsibility. You might say that the US should catch more of the opprobrium. You could say that over-expansionist fiscal and monetary policies (and lax practices by the banking community) fuelled an unsustainable consumer boom, and that China merely took advantage of that by selling the Americans the stuff they wanted. But if from now on the total Chinese surplus continues to grow, and hence grow against other countries too, that argument becomes harder to sustain. China will be seen to be carrying out a mercantilist policy: buying market share in the rest of the world and squeezing out competition by under-pricing its goods.

How does it under-price? The charge is: by keeping its currency artificially low. The bottom graph shows the yuan against the dollar. As you can see the long-standing peg was eased in 2005, allowing an appreciation, but then re-pegged in 2008. (A fall in number of yuan that a dollar buys obviously means that it is getting stronger against the dollar.) At the moment the peg is being eased again a little, following US pressure, and the general perception is that if it is allowed to rise another 10 per cent or so that should assuage Congress. We shall see.

The dollar/yuan relationship is the hot one, but by no means the only issue. The US is also being accused of deliberately trying to push down the value of the dollar, and countries such as Brazil feel they are being targeted. And elsewhere Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand and Colombia have all been criticised for trying to manipulate their currencies. Timothy Geithner, the US Treasury Secretary, said on Wednesday that "all of us will be worse off" if emerging economies did not change their tactics.

This is all very messy. We all tend to assume that the global trading system is robust enough to cope with currency strains, and looking at the past 40 years of floating exchange rates that would seem a reasonable assumption. There have been wild currency swings but countries have learnt both to hedge their currency exposure and develop contractual and manufacturing patterns that can cope with unexpected movements. But when the problem is not a currency fluctuation but a deliberate undervaluation, things become tougher.

The really big issue here, and this will be key during the debates before and at the annual meetings of the IMF and World Bank in Washington this weekend, is that economic power is now with the emerging economies. They are the ones that are growing fastest and which largely escaped the recent recession; indeed in the emerging world taken as a whole, there was no recession at all. Unsurprisingly and indeed correctly, these countries want a greater voice in IMF decisions. But as Dr Strauss-Kahn said, countries that want to have a greater say also need to accept more responsibility for maintaining a healthy global economy.

What happens next? Well, let's see what is said in the next few days and more importantly, how China and the US manage to keep simmering tensions in check. But the plain fact is that unless Asian countries save less and spend more and unless America saves more and spends less, these global imbalances will remain. And ultimately the rest of the world has to decide on whether to go on lending to the US. I suspect that the greatest tension in the future will not be over trade but over investment. Does the US really want its property and its companies bought up by Chinese investors? It may be all right having foreigners owning your national debt (though frankly I feel uneasy at the extent to which we in the UK have borrowed from abroad to finance our deficit) but when they buy tangible assets, then being owned by foreigners becomes harder to swallow.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies