US unemployment and Syria have clouded the picture over tapering

Global Outlook: No action next week will certainly throw off the markets

To taper or not to taper: that will be the question confronting members of the US Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee when they meet next week. Until recently, the answer seemed clear.

With economic trends showing signs of steady improvement, the Fed was expected to use next week’s meeting to announce the beginning of the end of its bond-buying programme by cutting the size of (or tapering) its purchases. But the picture has become more complicated of late.

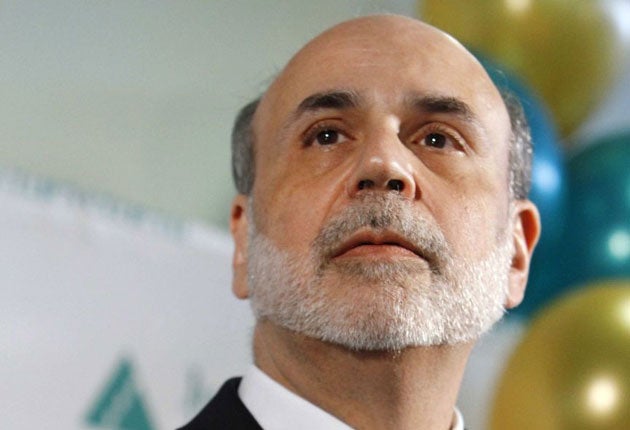

To recap, the programme is currently worth $85bn (£54bn) per month. Economists began anticipating a reduction following remarks by the Fed chairman, Ben Bernanke, in June, when he outlined a rough timetable that, depending on economic trends, the central bank might follow as it considered reducing the magnitude of extraordinary support it was extending to the US economy: a cut in the programme “some time later this year” and a complete halt “somewhere in the middle” of next year. He also explained that the bank expected to end the programme when the unemployment rate in the world’s largest economy fell to 7 per cent.

On the face of it, last month’s unemployment report would suggest the Fed will announce a cut next week. After all, the national unemployment rate declined to 7.3 per cent. If the bank wants the bond-buying programme to end by the time the rate retreats to 7 per cent, next week would, it seems, be the right time to announce the first in what would be a series of cuts.

The problem is that the unemployment rate fell for the wrong reasons: a drop in the labour-participation rate. In other words, the unemployment rate did not improve as Americans were finding jobs.

Rather, it fell because a greater number gave up looking for work, such are the conditions in the US economy. A couple of years ago, 66 per cent of Americans either had a job or were looking for work. In August, the figure fell to 63.2 per cent – its lowest since the late 1970s.

Moreover, the August jobs report also contained significant revisions to the estimates for June and July. The US Labor Department lowered its estimate for the number created over the two months by 74,000.

Just to make things easier for the Fed, the Obama administration is gearing up for a possible strike on Syria. The prospect has led to volatility on the stock markets, and questions have been raised about the wisdom of any significant shift in monetary policy at a time of heightened, geopolitical uncertainty.

The net effect of these factors is that it is no longer clear what the Fed will do. Some, however, insist that it must taper, otherwise it will compromise its credibility. Will it?

No action next week will certainly throw off the markets. Investors have factored in a cut for months now, as evidenced by movements in bond prices, stocks and emerging-market currencies, which have been hammered by the prospect of monetary tightening (technically, a cut in the programme would not count as policy tightening, as the size of the Fed’s balance sheet would remain unchanged. But the markets are behaving differently, expecting any announcement of a taper to signal the beginning of a cycle of monetary tightening).

But, surely, the Federal Reserve should be more concerned about the economic backdrop than the expectations of traders in New York and London? One thing the bank should not do is pander to Wall Street.

Facebook’s problems have done Twitter a favour

Twitter’s bosses should send a thank you card to their colleagues at Facebook. Ordinarily, given the way over-hyped IPOs often work, Twitter’s listing plans would have sparked off a round of fevered speculation about how high it might be valued when it arrives on Wall Street. Analysts would have made silly predictions. Banks would have pushed the company to pitch its shares as high as possible. Headlines would have screamed out fanciful figures.

But given the problems that marred Facebook’s market debut in 2012 – the stock has only recently climbed back above the company’s too-high offer price of $38 (£24) apiece – Twitter’s bankers are likely to err on the side of caution.

Already, for such a hotly anticipated listing, the tone of the coverage is (relatively) restrained.

Although Twitter’s debut will be smaller than Facebook’s, everyone is talking about how the micro-blogging company could avoid the traps that handicapped the social-media giant’s shares for so long.

We will have to wait for more information about Twitter’s pitch to investors (the company has used a new regulatory rule to keep the initial listing paperwork confidential).

But, given Facebook’s high-profile problems, expect this debut to be more measured, which, in the long run, can only be a good thing for both the company and those who decide to invest in its shares when it lands on the stock market.

Size still matters with ‘too big to fail’ banks

Tomorrow marks five years since the collapse of Lehman Brothers.

The intervening period has brought untold pain to scores of ordinary people in the US and around the world as economies slowed down, companies shed jobs and overburdened governments slashed spending.

But on Wall Street, little appears to have changed, particularly with respect to a key issue which was hotly debated in the immediate aftermath of the Lehman collapse.

For a while, everyone was talking about the problem of “too big to fail” banks. The issue was in headline after headline.

However, figures compiled by Bloomberg show that the debate was pretty much pointless: there has been a 28 per cent increase in the combined assets of the six-biggest US banks since 2007.

Yes, it is true that big banks now hold greater amounts of capital as a buffer against potential problems. But the central problem of institutions that are so big that their failure would imperil the wider financial system (and indeed the wider economy) has gone unaddressed.

Five years on from Lehman, it looks as if some banks are too big to change.

And that’s not good for them – or for the rest of us who will be on the hook once again if something goes badly wrong.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies