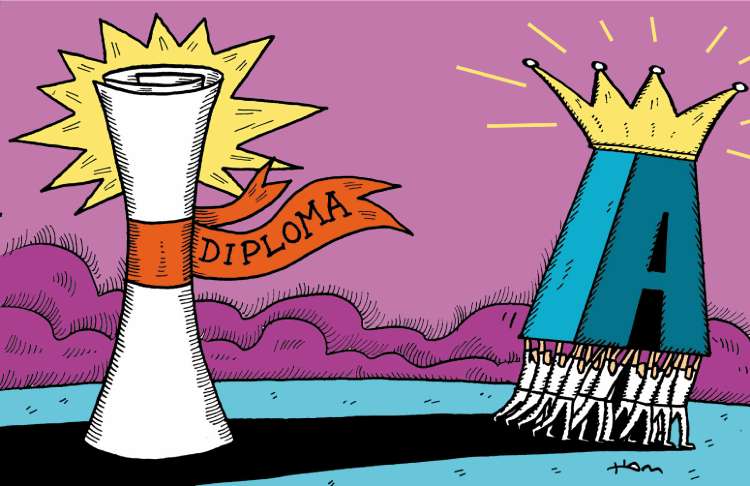

Bethan Marshall: Why schools will be sticking with A-levels

Last week I listened to Ed Balls, the Schools Secretary, talking about the new diplomas, which are to start in the autumn. Admittedly, it was first thing in the morning, but he sounded very keen; so keen in fact, that A-levels, which have been reformed for the start of this academic year, appeared to be on the way out. The following day I saw Mike Tomlinson, who wrote the big report on 14–19 education, talking on TV, or seeming to talk, about the demise of A-levels as well.

In his report, Tomlinson famously recommended getting rid of A-levels altogether and replacing them with diplomas. Having two qualifications at 18 as we do now, one A-level and one vocational, created a two-tier system with A-levels for the bright and vocational qualifications for the handy, he argued.

So he suggested scrapping them both. In their place he proposed an elaborate system whereby young people could do a combination of academic and vocational courses, including an extended project on a subject of their choice and work placements where appropriate.

What would be difficult, if not fatal, to his scheme, he felt, was to retain A-levels. Almost as soon as his report was published, Ruth Kelly, then education secretary, ignored his advice and did just that, retaining a divide between the two qualifications.

Tomlinson's desire to see the death of an academically elitist exam is understandable. But his arguments went beyond that last week. For example, he suggested the beauty of the new diploma in engineering was that it would give students who wanted to study the subject at university some higher level maths education just like they get on the Continent with the baccalaureate. One diploma would count for three A-levels – and that would include maths.

Or take the humanities diploma, which is being introduced in 2011. Young people, according to Tomlinson, will have a far wider grasp of a range of subjects than they do now. Although this diploma has not yet been finalised, it will include aspects of English, history, geography and perhaps religious education too. This, he says, can only be a good thing.

Listening to Tomlinson, then, A-levels are dead. Long live the diploma. But herein lies part of the problem. A-levels are not dead. In fact they are very much alive and have been reformed.

They are targeted at the academically inclined. The diploma, by contrast, is aimed at young people getting Cs or Ds at GCSE and who would struggle with A-levels. The argument is that they are not suited to traditional academic courses and would be better off with a test that includes workplace learning as part of their assessment.

But this leads to problems as well. Schools will find it difficult, if not impossible, to find students the placements they need. Further education colleges may find it easier because they have the connections with the world of work, but, if colleges become the institutions that are able to lay on the diploma, that will create a division in the way young people are educated. Schools may still do A-levels while colleges, where they can, do diplomas.

Even colleges could have problems finding, say, a placement for a young person taking a media diploma if they live in Biggleswade or Frome.

Then there is the split in the kinds of children who do the diplomas. The new qualifications might not have the title vocational in them but that is the way they are being seen.

Clever children will do A-levels and the rest will do vocational qualifications because nobody, apart from anything else, has explained to teenagers and adults how the system will be as flexible as A-level.

With A-levels, 16-year-olds decide on subjects of their own choosing. They can study maths and history; biology and geography, even film and physics if they want.

Although Mike Tomlinson claims that this will be possible with the new diplomas too, nobody, not even Tomlinson himself, can explain how. The divide, which he fought so hard to quash, will still be there.

Schools may decide to embrace the new qualification. Some may be enterprising and offer to do ICT or media. They may do their best to work with outside agencies, with colleges and places of work. But most will stick with what they know. Employers may do the same. Many leading entrepreneurs will stay loyal to A-levels because they are familiar with the qualification and don't know exactly what the diploma contains.

For all his enthusiasm now, Ed Balls may find that, when they are old enough, his own children choose to take A-levels. Diplomas may seem like a good idea now but they are possibly best for other people's offspring, not one's own.

The writer is senior lecturer in education at King's College London

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies