Could a later start to the school day be the most useful educational reform of all?

Doctors want a later start to the school day so that pupils can sleep later. Not because teenagers are lazy, explains Simon Usborne - it's all down to their circadian rhythms

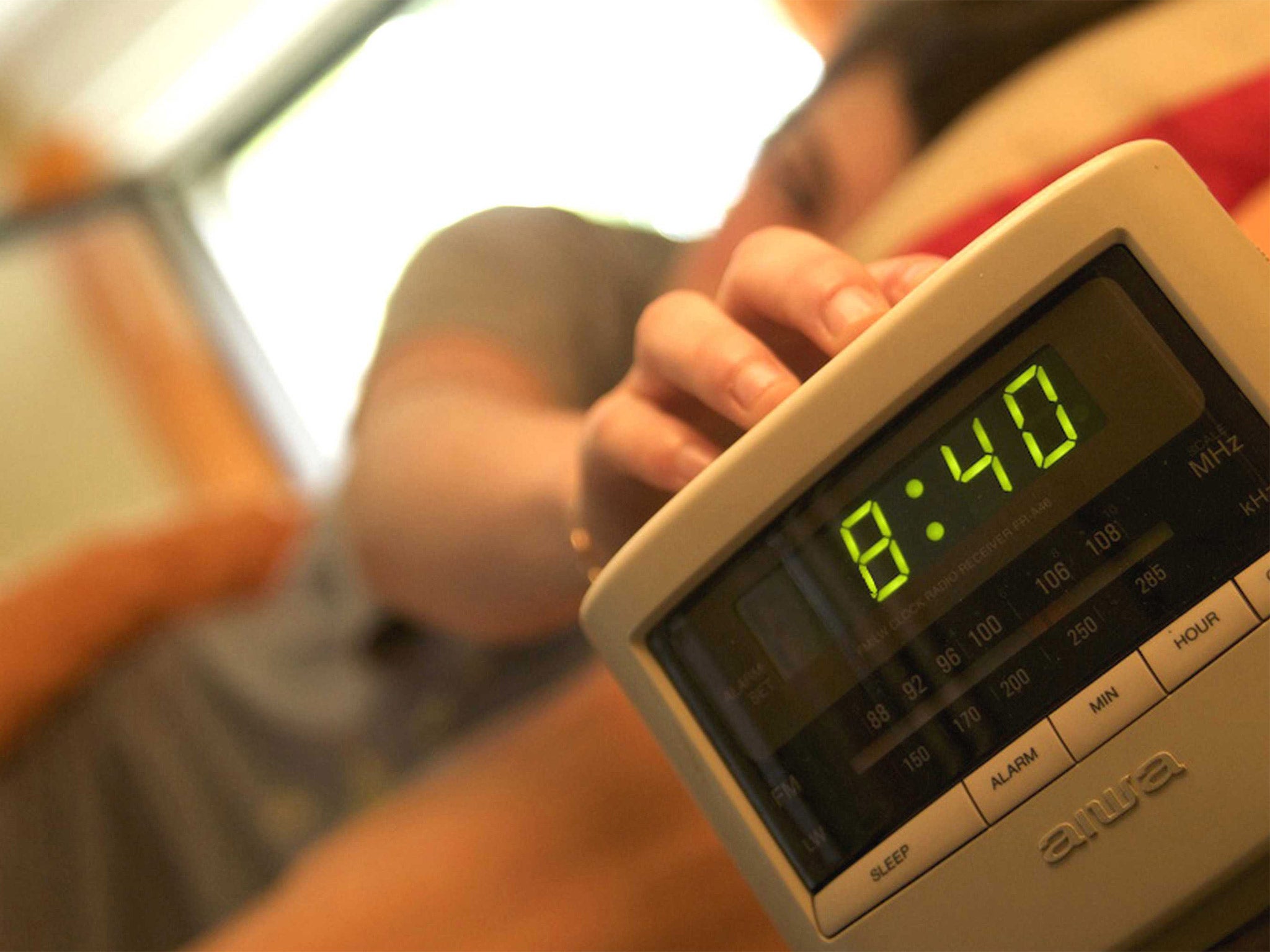

Summer is expiring, the mornings already feel shorter and now, for families across the country, it's that dark time of year when we reacquaint ourselves with our alarm clocks and – whisper it – go back to school (although children in Scotland went back two weeks ago).

But, as scientists and forward-thinking teachers wake up to the shifting demands of the brain, why do we do it to ourselves?

Next year, a handful of students in Surrey will discover a new way to work. When Hampton Court House opens a sixth form in September 2015, classes will start at 1.35pm and end at 7pm. The change will offer students the chance to sleep later, which is what teenagers do best, but not because they are lazy (even if they do happen also to be lazy).

In America, where almost half of schools have start times before 8am, doctors this week called for an urgent delay to the school day of at least half an hour. The American Academy of Pediatrics said that doing so would boost productivity and reduce the sometimes serious effects of sleep deprivation, including car accidents.

This is old news for Dr Paul Kelley, who works with the Sleep and Circadian Neuroscience Institute (SCNI), at Oxford University. He was the headmaster of Monkseaton high school in North Tyneside when it made headlines in 2010 by pushing the start of Period One back to 10am. "It had a positive, measurable effect on academic progress and health," he says. Early improvements included a drop in absenteeism.

"There's a growing case that shows that the time shift of sleep patterns in teenage years is biological, involuntary and happens to everybody – like puberty itself," he adds. "It shifts the sleep cycle two to three hours later by the time you've reached 20, when the scale of sleep loss is the worst you will encounter in your whole life."

By the time the average person reaches 90, he or she will have spent 32 years asleep, yet we are still unravelling the quirks and mysteries of circadian rhythm. In a talk last June, Russell Foster, head of the SCNI in Oxford, began by recounting changing attitudes, from "Sleep is the golden chain that ties health and our bodies together" (Thomas Dekker, Elizabethan dramatist) to "Sleep is a criminal waste of time and a heritage from our cave days" (Thomas Edison, bringer of light) and Thatcher's "sleep is for wimps".

"At worst, perhaps, many of us think of sleep as an illness that needs some sort of a cure," Foster went on. In fact, sleep has a vital role in restoration, energy conservation and, most importantly, the consolidation of memories and boosting of creativity, areas which are busier when we sleep.

Endemic sleep deprivation, therefore, particularly among shift workers (and somnolent teens) is leading to depression and mental problems. It can even make us overweight. "[It] seems to give rise to the release of ghrelin, the hunger hormone," Foster explains. "Ghrelin is released. It gets to the brain. The brain says, 'I need carbohydrates'."

In the simplest of terms, we sleep because we are circadian creatures; we follow the cycle of day and night. "Certain bandwidths of light activate the brain," explains Dr Irshaad Ebrahim, who has established sleep research centres in London and Edinburgh.

"Come night time, [the hormone] melatonin starts being secreted and we go to sleep."

While most of us recover a more regular pattern in adulthood, Kelley says, "it takes until the age of 55 until you get back the sleep/wake times you had when you were 10." Genes are also important. Late risers are more likely to give birth to late risers, and not just because that's how they are raised. This variation has been evolutionarily important, Kelley adds. "As a group of hunters, you have more time to hunt, for example."

But Ebrahim warns against pushing back the school day too far. "1.35pm seems a bit extreme," he says. On its website, Hampton Court House suggests that the free mornings "open up a huge range of work experience and community service opportunities". But scientists familiar with the habits of teenagers (Kelley has raised four children) agree that this is optimistic.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies