A treasure trove of film from the BBC archives goes online

From early documentaries to comedy gold, the BBC’s vast archives are finally being made instantly accessible

I'm in the depths of the vast BBC archive, a collection of 12 million artefacts including 600,000 hours of television content and 350,000 hours of radio.

With its endless shelves of Beta tapes, VHS and DVDs and row upon row of canned film stored together like weights in a gymnasium, this former greetings card factory in an industrial estate near London's Heathrow Airport, is but one of 25 buildings across Britain that house this extraordinary resource. At Caversham in Berkshire there are more than six miles of BBC documents; the contracts, correspondence and expenses claims behind eight decades of broadcasting.

As licence-fee payers we have funded all this, and as modern media consumers we have come to expect access to it – on demand. In 2006, an age ago in modern media terms, Ashley Highfield, then head of technology at the BBC, told me we were fast approaching a world where the greatest film archive on the planet would be ours to play with, to mash up our own compilations of our favourite shows and presenters. So where is it?

Well, go to the BBC Archive site now and you'll find 34 themed collections available to browse. "Life Under Apartheid" is a portfolio of 22 programmes made between 1954 and 1996. It includes a remarkable episode of Panorama from 1964 showing a young Robin Day reporting from Nelson Mandela's trial in Pretoria, together with a typed letter from one of Day's cameramen on how he fought with Nationalist thugs who tried to stop him filming. Another collection, "Suffragettes", contains a 1958 radio interview with Winifred Mayo, who tells plummy interviewer Donald Milner just how much she enjoyed smashing the windows of the Guards Club in Pall Mall back in 1912, while a young Joan Bakewell can be seen chairing a BBC2 discussion on women's rights in 1968.

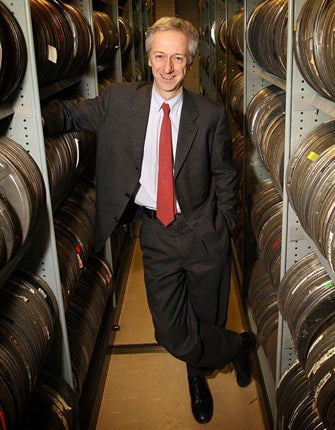

After three years of work, 50,000 hours of visual content have been digitised, but that's less than 10 per cent of the total and the great majority of what's been converted is not available for public view. It is Roly Keating's task to open up this archive, where the corridors are lined with pictures of the stars from the BBC's past, from Morecambe and Wise to the Paramount Astoria girls who took part in the first televised revue in 1933.

A former documentary-maker, Keating has become one of the corporation's most senior figures, a former controller of BBC Four and then BBC Two. He accepts that it is no longer good enough for broadcasting to hide away its treasures. "Audiences that have grown up with the internet – that means all of us now – have come to expect that they can, for a price, access almost everything from the past. The word 'archive' is not something you would acknowledge in film or music or literature. Casablanca is not an archive movie, Blonde on Blonde isn't an archive album, it's just music," he says. "We are trying to get the best of broadcasting on to that same footing so that it is immediately accessible to people."

Keating has big ambitions. He is about to release on to the BBC Archive site a collection of 15 pieces of video on Henry Moore, including the groundbreaking films made with the sculptor by the pioneering documentary-maker John Read. That will be followed by a collection on feminism, to accompany a major BBC television series on women. Doctor Who – which already has an online archive of its earliest programmes – will be the subject of a new retrospective looking at how the BBC has coped with the 10 variations in appearance of the Time Lord. Other upcoming collections will be themed on the Battle of Britain (to mark its 70th anniversary later this year) and on great examples of war reporting.

This is merely scratching the surface, but though we licence-fee payers have financed this creativity we should not have unlimited free access to it, Keating warns. "This is not about everything being made available for free," he says. "For generations we have got used to buying DVDs or VHS copies of the most popular programmes and long may that continue, that's a proper reward for the performers, writers and producers of those programmes."

This venture is partly about making money, for the creative community, the BBC's commercial arm and its partners. Those who want to seek out the niche content, the special-interest gems, may have to pay for a permanent download. "Our job is to work closely with the commercial market to make paid access ever easier for audiences," says Keating. "It's not our job to use the licence fee for all of this."

A parallel BBC project to digitally catalogue every single programme made by the BBC since its inception in 1922 will help us to know exactly what is in the archive and what is accessible for free or to purchase. This record, Keating says, will include programmes that no longer exist. A pilot exercise is being conducted for 1948, using digitised press listings to enrich descriptions of programmes. Keating himself added background to one 1948 poetry broadcast presented by Alex Comfort. "I put my hand up and said 'Is that the same Alex Comfort who wrote The Joy of Sex in 1973?' It's the same guy."

The broadcast content can be given context through publication of the programme's behind-the-scenes documentation. "The BBC has contracted or corresponded with almost every important figure of the 20th and 21st centuries," says Keating.

The biggest hurdle to releasing archived material is rights ownership. "The key fact is that the public own some but not all of the amazing programmes in this archive, in many, many cases those rights are shared, quite rightly with the authors, musicians and performers engaged in the original creation of those works."

Keating has watched with interest as Google has met with legal resistance from national governments and publishers over plans to scan and distribute millions of books online, including large numbers of "orphaned" works where the author is unknown.

The rights contracts for many items in the BBC archive are outdated. "Contracts may have been built for a 20th-century linear broadcasting age where in many cases nobody thought the programme would have an enormous afterlife or at best might get sold on VHS or DVD," he says. "Even in the last 10 years as we've been more sophisticated in the way we have worked with rights partners to frame these partnerships, it has been impossible to keep pace with the sheer rate of change that the internet has driven. We need agreements that work for this era."

But he is not frustrated that he cannot release all the material straightaway. "I often talk about this as a decades project to avoid any sense this should happen overnight – it shouldn't because we will make mistakes and spend money unwisely," he says. "If everything happened at once it would be hard to know where the real excitement and value was. The work of liberating sections of content should be a creative one."

Keating is especially excited about making available the "fantastic national resource" that is the archive in BBC journalism. He thinks there may be commercial opportunities for partners of the BBC to make available historic footage of British comedy and dance.

It's not a simple challenge. "Once we thought we understood scheduling and running channels," observes the archive head. "It's a whole new world this."

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies