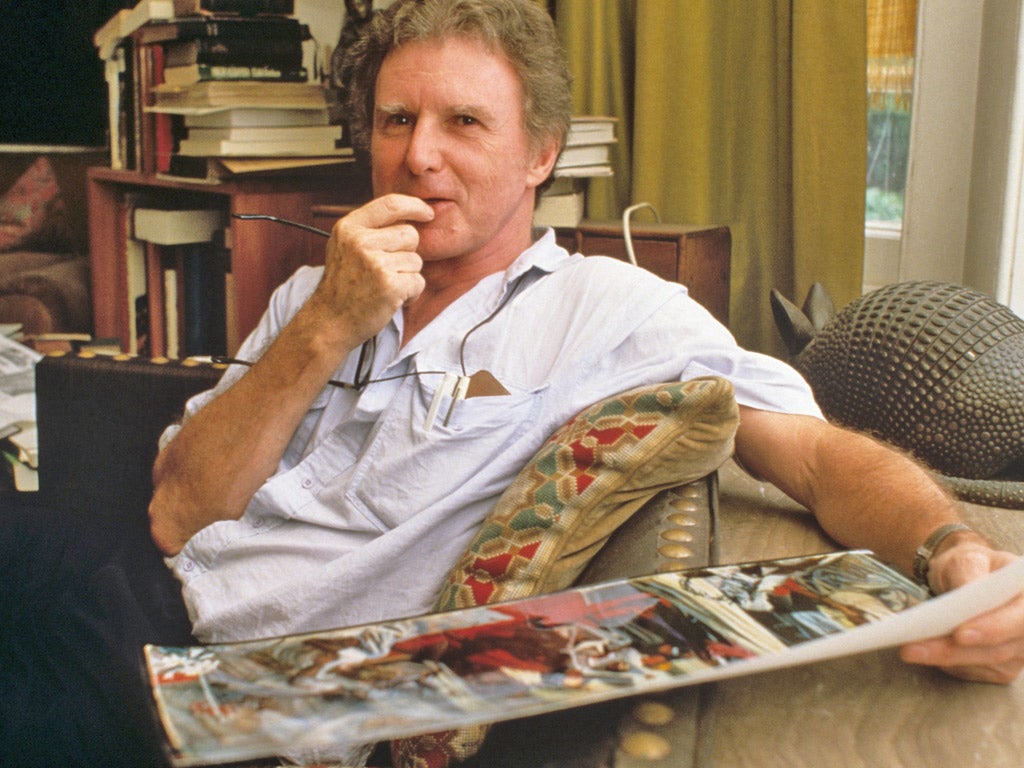

Brian Sewell: Critic both loved and cursed for his insistence that most – though not all – modern art is rubbish

‘When not reviewing my exhibitions, Mr Sewell can be sweet,’ wrote Grayson Perry

He was, he said, “cursed with the voice of an Edwardian lesbian”, the second syllable of the second-to-last word rhymed, à la 1907, with “lard” rather than “sword”. Of the numerous striking things about the critic, Brian Sewell, who has died of cancer at the age of 84, the most immediate was his locution. His voice, as he said, belonged not just to a different sex, but to another time. As a result, the views it pronounced on art were assumed to be old-fashioned, although this was not always the case.

Along with Sewell’s voice went an archaic vocabulary – “callipygian” was a favourite word, as was “panjandrum”. Neither applied, in later life, to the critic himself. Although something of a beauty in his youth, he had acquired the spun-sugar look of a Chelsea dowager by the time he arrived on British television screens, via his job as art critic on the London Evening Standard, in the mid-1990s. In an era when knee-jerk modernity was the order of the day, his insistence that most contemporary art was rubbish made him a pariah in that powerful part of the art world he dubbed “the Serota tendency”.

Far from resenting his exclusion, though, Sewell revelled in it: he called the first volume of his two-part autobiography Outsider. This book caused horror among his aged female devotees for its recounting of a lurid homosexual past. Sewell confessed to having had “easily a thousand sexual partners in a quinquennium” in his thirties – a revelation made all the more salacious by imagining its last word spoken in the author’s own voice.

Beneath the baroque vocabulary and brazen gay encounters, Outsider had a sadder story to tell. If written with the same remorseless lack of sentimentality Sewell brought to his criticism, what emerged from its pages was a life shaped by illegitimacy, class consciousness and a lack of love.

Sewell’s mother had had him out of wedlock in 1931, at a time when such things mattered. Worse, in her son’s own snobbish telling, she had then married a middle-class man whose surname Sewell was tricked into taking, and who had sent him to an undistinguished London day school.

Although hinting strongly in Outsider that his mother earned her keep by providing sexual favours to men, Sewell lived with her in a house in Eldon Road, Kensington, until her death in 1996 when he was 65. Only as she lay dying did she finally reveal that his biological father had been Philip Arnold Heseltine, better known as the composer, Peter Warlock. Like his (unacknowledged) son, Warlock had earned his living as a critic. Like his son, too, the composer had led a rackety life, experimenting with drugs and living in a bisexual ménage before gassing himself at the age of 36, seven months before Sewell was born.

Of the various deprivations Sewell might have felt from this unhappy childhood, the one that stuck most obviously in his craw was its lack of a good public school education. The subtitle to Outsider – Always Almost: Never Quite – has more to do with a sense of being looked down on socially than sexually. (“I never came out,” Sewell said, happily, “but I did slowly emerge.”)

At the Courtauld Institute, he was taught history of art by Anthony Blunt, a Marlburian who had gone on to Trinity College, Cambridge. (In spite of this, Sewell’s loyalty to Blunt never failed.) At Christie’s, where he worked in Old Master paintings for two decades after leaving the Courtauld in 1957, Sewell conceived a violent dislike of David Carritt, a colleague who committed the dual sins of being a better connoisseur and a Rugbeian. After a particularly acrimonious row between the two, Carritt’s expensive new covert coat, hung on a hook, was found to have been slashed by an unknown hand. Sewell left Christie’s soon afterwards.

It was after a decade as a private dealer that he was given the job as art critic of the Evening Standard, the role for which he was to be best known. His predecessor at the paper was the pro-modernist Richard Cork, and Sewell wasted no time putting as much distance as he could between Cork’s critical views and his own. To general surprise, this quickly earned him a cult following. The ruder and more retardataire Sewell became, the more his audience loved him.

When he wrote in this newspaper that “Only men are capable of aesthetic greatness… There has never been a first-rank woman artist,” glasses were raised to his health at the bars of golf clubs up and down the country. Attacks on Northerners, Bristolians, Sister Wendy Beckett (Sewell once appeared on television dressed as the hapless nun), Britart and Sir Nicholas Serota only fanned the flames of his appeal.

The Standard’s critic acted his part with gusto, becoming ever more like himself. This culminated in 1994 in 35 members of Sewell’s “Serota tendency” – gallerists, artists and a number of fellow critics – writing a letter to the Standard in which they accused him of misogyny, homophobia and trading in “formulaic insults and predictable scurrility.” Sewell could not have been more delighted.

While fortunate in winning him stardom – he enjoyed his role as a TV personality above all others – the need to play up to his public persona made Sewell seem increasingly mono-dimensional. This was particularly so in his response to contemporary art. At a meeting of members of the National Art Collections Fund (now the Art Fund) in the 1990s, Sewell horrified his audience by suggesting that Damien Hirst might actually be “really rather a good artist.” (“I would get him away from that frightful dealer of his, though,” he went on, to a chorus of relieved sighs.) A decade later, he would dismiss Hirst in a review as “fucking dreadful.” Although many of his readers will recall his blistering attacks on, say Tracey Emin, few are likely to remember Sewell’s reasoned defence of Jake and Dinos Chapman.

The other disadvantage of notoriety was that it obscured Sewell’s deep learning, genuine passion and abiding kindness. If he insisted that his knowledge of art came from years spent trawling stately homes for Christie’s rather than at the Courtauld, that knowledge was none the less there. No other newspaper critic writing today can do so with anything like his scholarly authority. If he wrote that David Hockney was “a vulgar prankster… trivialising paintings that he is incapable of understanding,” then he did so with those paintings clear in his mind. And Sewell’s attacks were heartfelt. When, in 2012, I met him in a room of Hockney’s studies after Poussin at the Royal Academy, the elderly critic was puce with rage. “Have you ever,” he hissed, Sewell-like, “been in the presence of such… effrontery?”

After his mother’s death, Sewell, himself ailing from osteoporosis and a series of heart attacks, moved to a vast house in Wimbledon. This was intended as a home for the growing pack of stray dogs which he picked up on his travels, and on which he lavished a love he found difficult to show for his fellow man.

If artists could be reduced to tears by Sewell’s attacks, then the death of his dogs had the same effect on him. His reviews for the Standard were interspersed with eulogies for dead greyhounds, as well as with hymns of praise to the classic cars he adored but was no longer able to drive. Latterly, he was asked for his views on everything from Prince Harry’s naked bottom to The Great British Bake-Off, and made a documentary for Radio 4 on his unlikely love of stock-car racing.

As is the way with national institutions – he was certainly one of those by the time of his death – Sewell’s foibles came to be overlooked by many of the people who had once hated him. When Naked Emperors, a collection of his contemporary art reviews, was launched at the Standard in 2012, Charles Saatchi sent a message thanking the critic for “always being so Brian Sewelly”. The Turner Prize-winning potter, Grayson Perry, often the object of Sewell’s vitriol, reviewed the book in a Sunday newspaper: “When he is not writing about my exhibitions,” Perry wrote, good-naturedly, “Mr Sewell can be sweet.”

As to the man himself, his summing-up of his own life was typically unsentimental. “I really think I am like my father,” he wrote of a man – or possibly two – that he had never known. “We both saw out careers as having ended in failure.”

Brian Sewell, art dealer, writer and television personality: born London 15 July 1931; died 19 September 2015.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies