David Coleman: Sports commentator and presenter

Giant of British sports broadcasting whose sheer professionalism kept him at the top for four decades

From the 1950s, when he became one of BBC Sport’s young bucks, until he bowed out at the end of the Sydney Olympics in 2000, David Coleman was, in that time-honoured phrase, “the voice of sport”. He combined authoritativeness with a palpable passion for what he was covering. Concision, he knew, was the key, and on hearing of his death every football fan over the age of 50 will have heard his crisply delivered “1-0” in their heads.

It was that passion that made him stand out. David Hemery, who won Olympic gold for Britain in the 400 metres hurdles in Mexico City in 1968, once recalled, “I remember him screaming, ‘Hemery of Great Britain, Hemery of Great Britain ... He crucified them, he killed the field.’ What was so special was just his identification with the delight of it. The delight was expressed by the range of octaves through which his voice went.” Once, famously, he nearly cried on the job, when Ann Packer took the 800 metres gold in Tokyo in 1964. “Oh, fantastic run, oh, fantastic run, magnificent, magnificent, magnificent,” he said, his voice cracking with emotion.

Perhaps unfairly, his name became a byword for commentating gaffes, and in the 1980s his breathless style was a gift for Spitting Image: in one sketch he reached fever pitch as Sebastian Coe broke for the line with 600 metres to go. ‘’And I’ve gone far, far too early!’’ his puppet screamed. “I’ll never be able to keep up this level of excitement!”

He was also a gift to Private Eye, who started its “Colemanballs” feature in his honour, and it continues to collect broadcasting howlers to this day. Although what’s remembered as the archetypal Colemanballs – “and Juantorena opens his legs and shows his class!” – wasn’t his but Stuart Pickering’s, Coleman made many sterling contributions to it over the years, with immortal lines like “That’s the fastest time ever run, but it’s not as fast as the world record” or, “there is Brendan Foster, by himself with 20,000 people.” Or ,“We estimate, and this isn’t an estimation, that Greta Waltz is 80 seconds behind,” or indeed, “for those of you watching on black-and-white sets, Everton are wearing the blue shirts.”

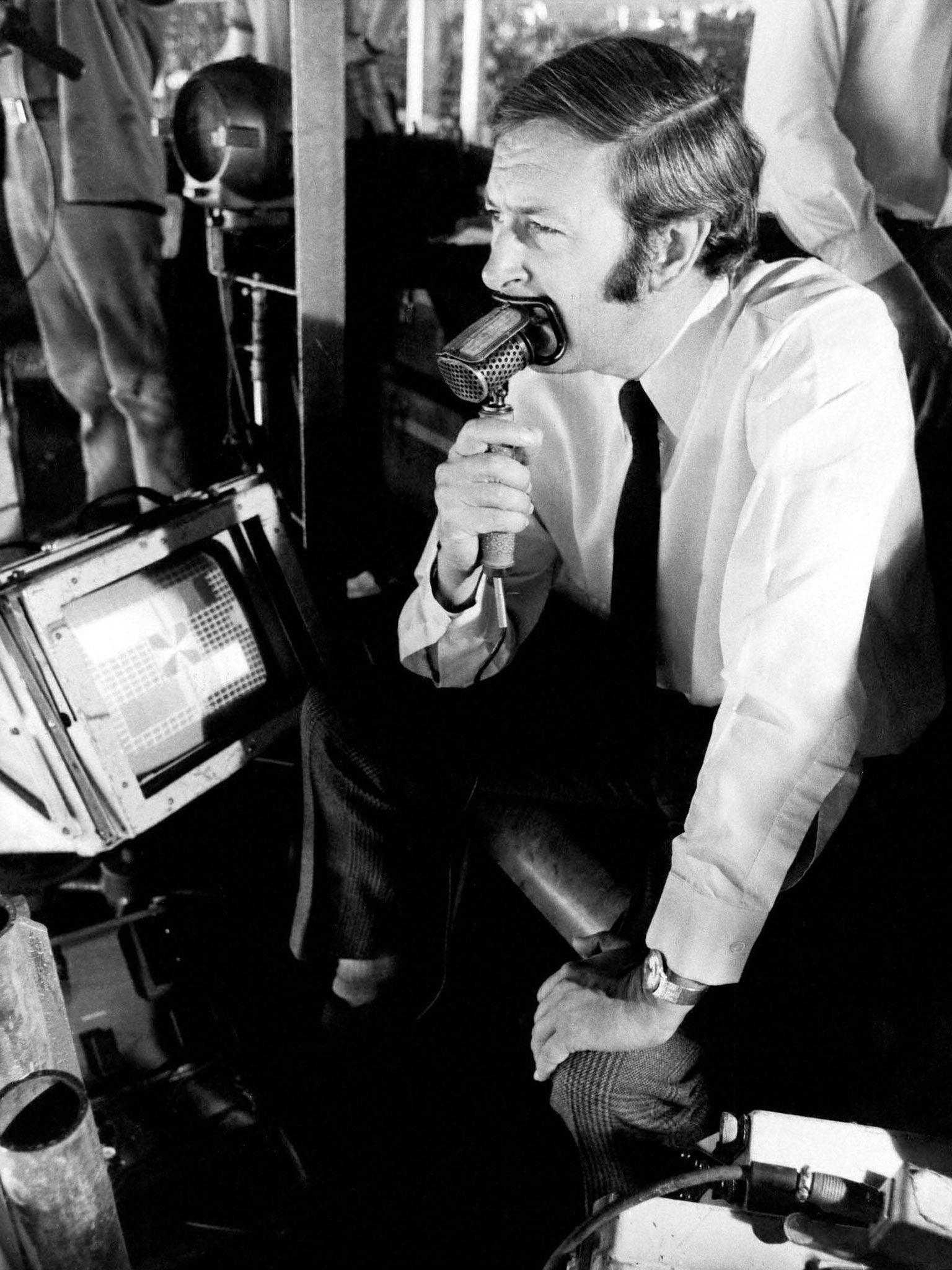

Many of his gaffes are less of a judgement on Coleman’s abilities than an indication of just how difficult live commentary is. As he once admitted, “We do occasionally get over-enthusiastic, but viewers don’t understand sometimes the pressures we work under.” Certainly, in the studio he made very few mistakes. A BBC sports producer who worked with him in the 1960s and ’70s recalled his “tremendous ability to concentrate and to deal with streams of information both in front of him on paper, and coming direct through his earpiece.”

David Robert Coleman was born in Cheshire in 1926, the son of Irish parents, and was a promising sportsman – he was the first non-international to win the Manchester Mile, for Stockport Harriers in 1949, and was a decent footballer, turning out a few times for Stockport County reserves. A contemporary remembers him as “very good-looking, a very good dresser, and never lost his form under pressure”.

He did his National Service in the Royal Signals Corps, and also worked for the British Army Newspaper Unit. Injury problems meant that his sporting potential remained unrealised – he missed the trials for the 1952 Olympics with a hamstring injury – and he decided to concentrate on journalism (his love for athletics endured, and he was later president of Wolverhampton & Bilston Athletics Club). He had started out on the Stockport Express and moved through a succession of local papers – at 22 he was editor of the County Press in Cheshire, and also had a stint as a news assistant on a Birmingham paper – then began freelance work with the BBC in Manchester.

He was perfectly placed to join the BBC’s sporting revolution. He was spotted by the BBC’s inspirational Head of Sport, Peter Dimmock, who wanted alternatives to the Oxbridge cliques which still dominated broadcasting. Dimmock recruited him to front a new programme which the Radio Times heralded as “a new-style, non-stop parade featuring sports where they happen, when they happen”. It was called Grandstand, and it gave Coleman the chance to become the first BBC front man without a cut-glass accent.

It was a time when the BBC’s sports coverage was expanding rapidly, and with immense foresight Dimmock was able to pin down many of the top sports events to long-term contracts, and also secure listed protection by Parliament – what became known as the “crown jewels”. Coleman was the perfect fit for Grandstand, displaying his immaculate professionalism towards the end of Saturday afternoons as the football results came in on the teleprinter. A 1-1 draw between Third Lanark and Queen of the South might elicit the instant observation that it was the home team’s third score draw of the season, sending them up two places to third in the table, while it was the away side’s ninth game in a row without a clean sheet. As he was speaking, the next result would be coming in, and he was invariably ready with another nugget of information.

He was also beginning to demonstrate his commentating abilities, and he gave a memorably censorious broadcast from the 1962 World Cup – the pugilistic confrontation between the tournament hosts, Chile, and Italy in what became known as “the Battle of Santiago”. “The game you are about to see,” he warned viewers, “is the most stupid, appalling and disgraceful exhibition of football, possibly in the history of the game.” Match of the Day began in 1964 and Coleman became a fixture of the commentary team alongside Kenneth Wolstenholme.

In 1968 he was a big enough figure to be given his own midweek programme, Sportsnight With Coleman, which he fronted until 1972 (when it became simply Sportsnight and ran until 1997). However, although by the 1970s he seemed to be ubiquitous on our screens, in fact a legal wrangle with the BBC in the mid-1970s kept him off the screen for a year; he complained that he wasn’t being used enough and was being kept out of the editorial loop.

The dispute revealed a hard-headed side to the man whose affability was one of the ingredients which made A Question of Sport, which he presented from 1979 to 1997, such a success – thanks in large part to the rapport Coleman established with the likes of captains Emlyn Hughes, Bill Beaumont, Willie Carson and Ian Botham – and he could demonstrate a short fuse when things didn’t go his way. Indeed, an audiotape of Coleman going off the deep end when a junior member of the team had made a mistake did the rounds of BBC parties for years.

On the other hand he was loved for his kindness and generosity. The athlete Steve Cram, who in retirement joined Coleman on the BBC athletics commentary team, described him as a huge influence on his career. “When I met him at major championships he would give me very helpful advice on travel and how to deal with the media,” Cram said. “He had a reputation for being tough and demanding, but I always found him an incredibly generous bloke.”

His sheer professionalism and competitiveness did mean that Coleman never cultivated close friendships with his rivals. When World of Sport began on ITV in 1964, Dickie Davies once recalled, Coleman’s reaction was short and to the point: “We’ll blow the bastards out of the water in six months.” And the great ITV football commentator Brian Moore once said of him, “We had a fairly spiky relationship, to be honest ... he set an agenda where there was no great friendship. I did find it very uncomfortable but I still respected him greatly.” Moore recalled meeting him when they were both covering the FA Cup final at Wembley: “We met round the back of the stadium by the scanner vans, and he said to me: ‘Oh, here he comes, seeking an inferior audience again.’”

For all his professionalism he could sometimes get it horribly wrong. When Don Fox lost his footing on the waterlogged Wembley pitch and famously missed a kick in front of the posts, losing the rugby league Challenge Cup final for Wakefield, all the march commentator, Eddie Waring, could say, was a deeply felt, “Oh, poor lad.” But in the tunnel afterwards Coleman was waiting for the devastated Fox.

“Don, it must be a desperate thing for a situation like that to occur,” he said. “Shocking,” replied Fox. “I’m that upset I can’t speak.” Undeterred, Coleman ploughed on. “Anyway, I’ve got some tremendous news, I know you don’t know. You’ve been awarded the Lance Todd Memorial Trophy for outstanding contribution on the field of play. That must be some consolation, surely?” It surely wasn’t.

One occasion when Coleman got things right was perhaps his finest hour – and it was a non-sporting hour. He was covering the 1972 Munich Olympics when Palestinian terrorists took Israeli athletes and coaches hostage, an attack which ended with the deaths of 11 Israelis, a West German police officer and five of the gunmen. Coleman held the fort for a day and a half, reporting on the crisis in an almost unbroken stint in front of the camera, as well as covering the memorial service a few days later.

He was widely commended afterwards for his professionalism and cool head, and the gravitas he brought to the BBC’s coverage of such a tragic event, and it was qualities like this for which he was awarded the OBE in 1992; he was also the first broadcaster to receive an Olympic Order medal, which he did at his last Games, in Sydney – when the BBC, shamefully, did nothing to mark his retirement. At the end of 2000, while the Corporation was going overboard about the fact that Murray Walker was planning to retire during the following year, the end of Coleman’s career was marked by a terse official statement that his contract was not being renewed.

Unlike today, when the doings of TV presenters tend to be a matter of public record, Coleman was self-effacing offscreen to the point of invisibility. Even at the height of his fame he lived quietly with his family in Buckinghamshire and gave few interviews. So low was his profile that the BBC was unaware in the early 1990s that his son was flying RAF jets in the Gulf War until they saw a Ministry of Defence press release. (Another child, his daughter Anne, was a champion show jumper.)

He was once asked what his favourite commentary line was. “As if I’d remember. Don’t be so bloody daft,” he said. Then he did remember. “Actually, there was one in the early days. When Herb Elliott won the 1500m in the Rome Olympics, I said, ‘And there’s the best in the world, running away from the rest of the world.’” Perfect. He covered 11 Olympics and six World Cups and, more importantly, was the authoritative sporting voice to which we turned for the best part of four decades. He was, in one of the phrases for which he was known and loved, “Quite remarkable.”

David Robert Coleman, journalist and broadcaster: born Alderley Edge, Cheshire 26 April 1926; OBE 1992; married Barbara (three daughters, three sons); died 21 December 2013.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies